In the 1970s, my parents and all the Jewish parents I knew had what I came to call the Jewish Bookshelf. On it sat “The Source” by James Michener, “Exodus” by Leon Uris, “The Chosen” by Chaim Potok, “Portnoy’s Complaint” by Philip Roth, “This Is My God” by Herman Wouk and “World of Our Fathers” by Irving Howe.

The first four were novels, shelved here in ascending order from lowbrow to highbrow. Wouk’s book is nonfiction, part memoir and part how-to about living an observant Jewish life. Howe’s is a classic history of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe.

Whenever I share this list with boomer friends, they nod in recognition, and a certain nostalgia for a time when Jews — or certainly suburban American Jews of the post-war era — were literally on the same page. The era that also gave us a synagogue building boom, the ever-more-lavish bar and bat mitzvah and the rise and fall of the Jewish Catskills was a middle-class, Ashkenazi monoculture. Our parents shared reading tastes in ways that seem to be unthinkable today, when media culture, like Jewish culture, has splintered. I’d be hard-pressed to pick five Jewish books from the last decade or two that I am confident could be found on the shelves of a present-day cohort of middle-aged Jews.

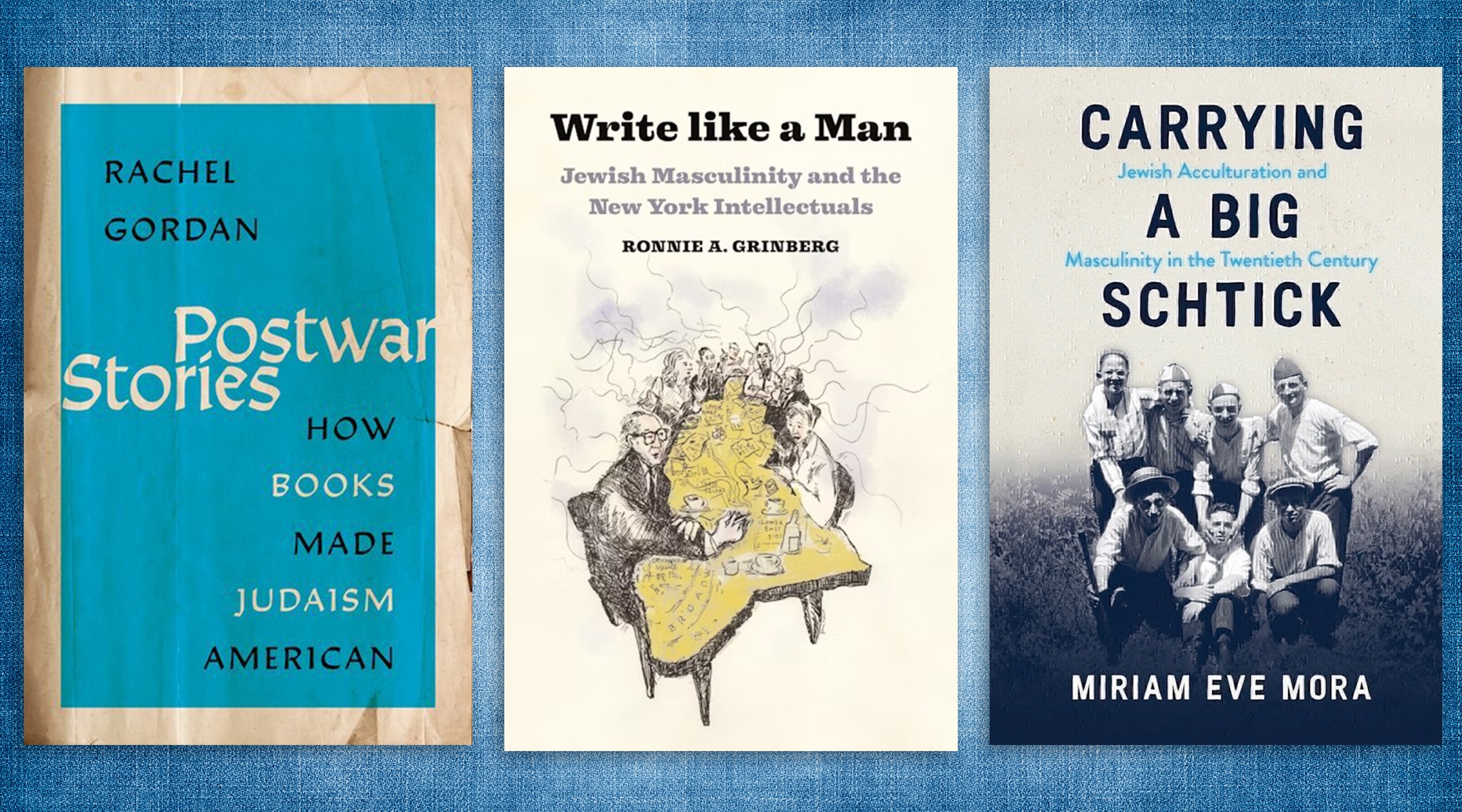

How that Jewish literary monoculture came to be and how it crumbled has become the subject of academic study, and of at least three books in the past year alone. The one that most directly focuses on the middle-class tastes of Jews like my parents is “Postwar Stories: How Books Made Judaism American,” by Rachel Gordan. An assistant professor of religion and Jewish studies at the University of Florida, Gordan examines what Jews were reading and writing in the period immediately following World War II. She’s less interested in the literary heavy hitters of the time — Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud and Roth, say — than in two very specific genres of middlebrow books.

The first she calls “Introduction to Judaism literature.” It includes Wouk’s “This Is My God,” “Basic Judaism” by Conservative rabbi Milton Steinberg and “What the Jews Believe,” by Steinberg’s cousin, Rabbi Philip Bernstein.

Many of these books — Gordan counts over 40 written between 1945 and 1960 — were marketed to the general public. Such books addressed non-Jews’ ignorance of Judaism at a time “when Cold War American citizenship seemed to require denominational affiliation.” (America, remember, was facing down the godless communists.) The authors of such Intro to Judaism books were also motivated by the suspicion that “American Jews themselves, not just non-Jews, were often ignorant about Judaism.” These children, grandchildren and even great-grandchildren of immigrants “stood at a remove from the religion of their ancestors.”

Gordan’s second genre is “anti-antisemitism literature,” epitomized by “Gentleman’s Agreement,” Laura Z. Hobson’s 1947 novel about a journalist who goes undercover as a Jew to experience antisemitism for himself (the film adaptation, starring Gregory Peck, won that year’s Oscar for best picture). Such works asserted that eschewing antisemitism and accepting Jews as part of the (white) American religious mainstream were essential parts of a “pro-democracy and anti-fascist worldview.”

Gordan argues that both genres helped transform American Jews and Judaism, turning them into “subjects that Americans could understand and accept.” Jews themselves, meanwhile, learned that their Jewishness did not have to be experienced as a liability. This led, by the 1970s, in two paradoxical directions: Jews embraced their ethnic identity in private and popular culture, but also assimilated into the mainstream and lost their Jewish distinctiveness.

It should be obvious by now that, except for Hobson, the writers I’ve mentioned so far are men. All of the recent scholarly works about this period are by women, and each addresses the gender gap. In the delightfully titled “Carrying a Big Schtick: Jewish Acculturation and Masculinity in the Twentieth Century,” Miriam Eve Mora writes how many of the male novelists, stung by antisemitic accusations that Jewish men were “feminized,” set out to “demonstrate the Jewish ability to perform masculinity on par with their national brethren.” She quotes historian Paul Breines, who describes the macho works of Uris, Roth, Mailer and Bellow as the “Rambowitz novels.”

Mora, the director of academic programs at the Center for Jewish History in New York City, analyses this attitude with some sympathy. The “view of Jewish men as weak or effeminate,” she writes, “has been a constant strain among popular sentiments about Jewish manhood in America, and there has always been a corresponding strain of Jewish men attempting to remedy this sentiment through proving or improving their manhood.”

Although best known as a novelist, Herman Wouk, seen here in 1975, wrote a nonfiction introduction to Orthodox Judaism, “This Is My God,” that became a bestseller. (Alex Gotfryd/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Somewhat less sympathetic is Ronnie Grinberg, a historian at the University of Oklahoma. Her book, “Write Like a Man: Jewish Masculinity and the New York Intellectuals,” studies the aggro posturing at “little” magazines like Commentary and Partisan Review and among their male contributors, including Norman Mailer, Lionel Trilling, Nathan Glazer, Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz. Besides exerting an outsize influence on the era’s debates over domestic and international affairs, they wrote and argued as if they were pounding the typewriter with their fists.

These writers absorbed American norms about manhood on the streets, at the movies and in popular culture, which together shaped “a new intellectual culture that valued a combative stance shaped by a desire and need to perform a new kind of secular Jewish masculinity.” The paragon of the New York Intellectual, Irving Howe once wrote, valued “pride in argument, vanity of dialectic, a gleaming readiness for polemic” — which was probably a lot more fun for readers than for the targets of their aggression.

Grinberg also writes about the women writers in this circle, often the wives of the gatekeepers, including Mary McCarthy, Elizabeth Hardwick and Diana Trilling. Not all were Jews, but they were willing to mix it up with the men in a style that came to be seen as distinctly Jewish.

Such “secular Jewish masculinity” shaped the intellectual discourse and the marketplace where work by men was taken more seriously. My parents — my mother anyway — read Jewish books by women, although they tended to be bestselling authors whose work was rarely regarded as great literature: Belva Plain, Cynthia Freeman, Judith Krantz. I don’t remember them reading books by Anzia Yezierska, Grace Paley or Cynthia Ozick, important writers often excluded in the talk about a golden age for Jewish American literature.

Gordan, Mora and Grinberg describe the forces that shaped Jewish identity, as well as reading tastes, in the 20th century: assimilation and acceptance, gender, the Cold War. Gordan explores how the Holocaust and the establishment of Israel also influenced the postwar literary era — the former by shaming or at least marginalizing antisemites, the latter by casting a glow of triumph and even cockiness over Jews living in the Diaspora.

What books would capture the Jewish vibes of the 21st century? In 2020 Yehuda Kurtzer and Claire E. Sufrin put together an anthology called “The New Jewish Canon,” attempting to catalogue the books and articles that represent the “Jewish intellectual and communal zeitgeist.” Among the 70 or so picks, only two could be called bestsellers: “When Bad Things Happen to Good People” by Harold Kushner and Joseph Telushkin’s “Jewish Literacy.”

It’s increasingly hard to talk about “Jewish community” when Jews are split along denominational, political and ethnic lines, and when the Holocaust and Israel are fading as forces that bind Jews to one another. My parents didn’t agree with their fellow Jews on everything, but they saw themselves in common cause. Their books they bought and read reflected this.

Perhaps the current lack of a common Jewish bookshelf of popular, middlebrow books is a good thing, hinting at a richly diverse community that can’t be captured between the covers of a handful of bestsellers.

Or maybe it points to an inability of a people to see themselves in each other, or agree on what they share.

Your turn: What books reflect our current Jewish moment — and which might you guess are on the shelves of even a plurality of American Jews? We’d like to hear from you: Suggest one or more general interest, scholarly and even cookbooks that have broken through to a wide readership and would tell a future historian what was on the minds of American Jews in the 2020s. Send your suggestions to asc@jta.org and put “Jewish Bookshelf” in the subject line.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.