WASHINGTON — Long ago, when Adam Schiff was in Slovakia on a temporary assignment from the U.S. Justice Department, he decided to seek out his family’s ancestral home in Lithuania.

The idea left his grandmother perplexed.

“I think she said something along the lines of, ‘We fought like hell to get out of there. Why would you want to go back now?’” he recalled in an interview last week.

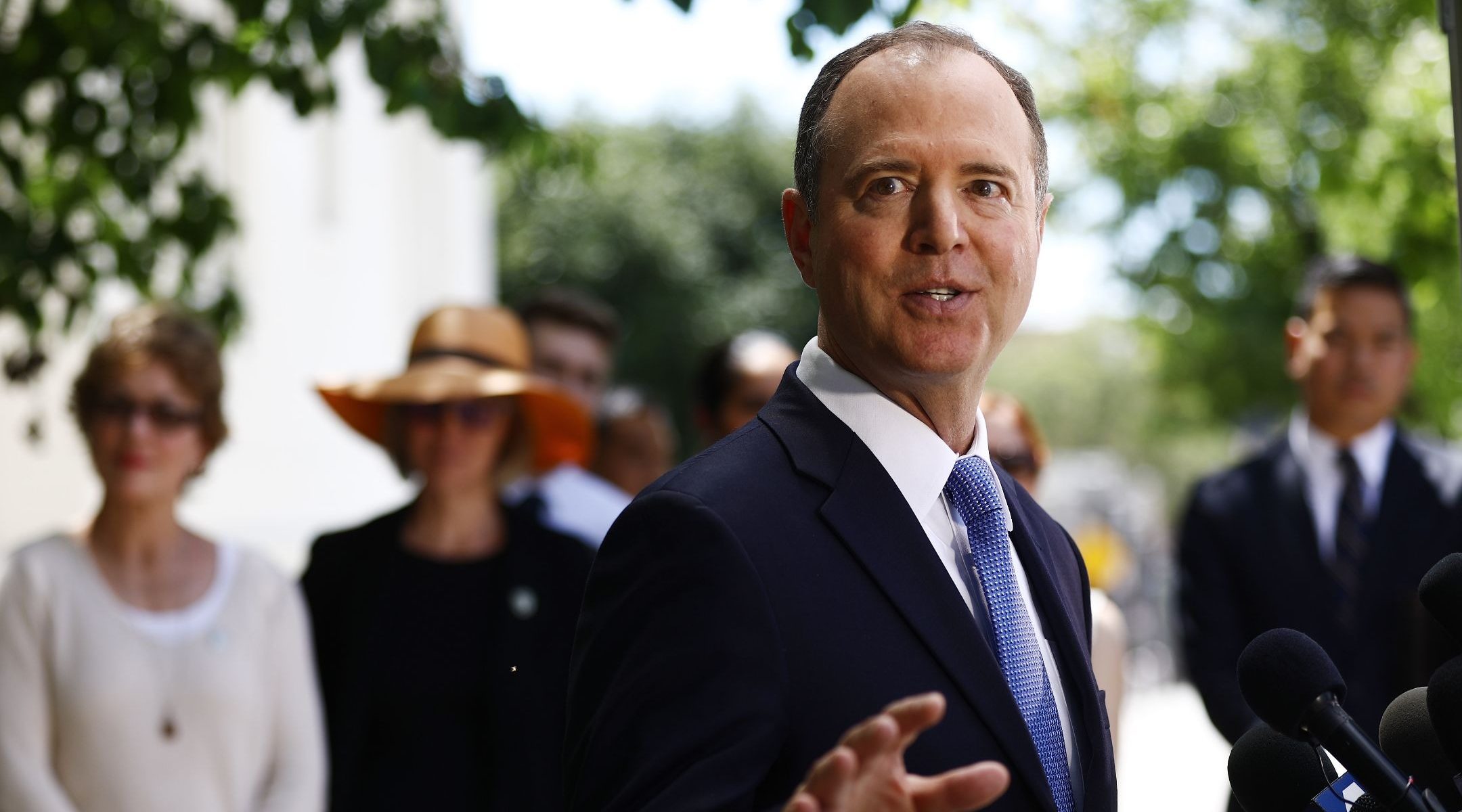

He went anyway, visiting the towns his great-grandparents had fled. Now, Schiff once again has a temporary title: senator-elect from California. And once again, he seems to be heading straight back into a situation that many others would flee.

The hostile territory, in this case, is Capitol Hill during a restored, and resurgent, Donald Trump presidency. Trump, livid at Schiff for investigating him and trying to remove him from office, has grouped the incoming senator under the broad category of “the enemy within,” a favorite phrase of the president-elect, and demanded that he be put to trial.

Schiff is not dismissing the prospect of legal action against him — especially when he looks at Trump’s nomination of former Rep. Matt Gaetz, who shares Trump’s proclivities for conspiracy theories and revenge. Gaetz’s nomination was stymied by a cascade of scandals, but Schiff says his name being put forward means “you can’t really exclude any possibility, right?”

So Schiff is enhancing his personal security — but said his wife and two kids asked him not to elaborate on that. He was more interested in drawing a link between Trump’s rhetoric about him and the broader threat he says the president-elect poses.

“They don’t want me to talk about it,” he said of the heightened security. “I mean, it’s more pronounced for me, I think, than many. But it’s not confined to me. It’s not confined to Congress. I remember talking to a school board member last year in the South Bay who said, ‘I’m not going to run for reelection. I have a young family. I’m getting death threats.’”

The exchange stunned Schiff. “You’re on the school board, you’re getting death threats. What? What’s happening?” he said. “And there is this very dangerous increase in the level of acceptance of the idea of political violence.”

Schiff, 64, said he feels the country is entering “totally uncharted waters” and is concerned about the threat Trump poses to democracy. It’s a shift from when he first entered Congress in 2001, after a career as an assistant U.S. attorney and four years in the State Senate. And he said he’s prepared to fight.

“Where it’s necessary to stand up to the president, to push back, to defend the rights and interests of Californians, I will do it, and I will do it unhesitatingly,” he said. “I think we are weak, very much weakened as a democracy. We are very fragile.”

Trump’s grievances against Schiff stretch back at least to 2019, when the California Democratic congressman led the first impeachment hearings against Trump. Schiff was also a member of the select committee to investigate the Jan. 6 Capitol riot that sought to overturn Biden’s 2020 election.

“These are bad people. We have a lot of bad people. But when you look at ‘Shifty Schiff’ and some of the others, yeah, they are, to me, the enemy from within,” Trump told Fox News Channel last month, using his nickname for Schiff that, with its suggestion of duplicity, some see as antisemitic.

And he’s already faced opprobrium: Republicans voted last year to censure him for his role in investigating Russian efforts to influence the 2016 elections, which Trump and his followers view as an overwrought and baseless partisan effort to delegitimize him. Schiff said he would wear the censure as a “badge of honor.” He was censured for “for misleading the American public and for conduct unbecoming of an elected Member of the House of Representatives.”

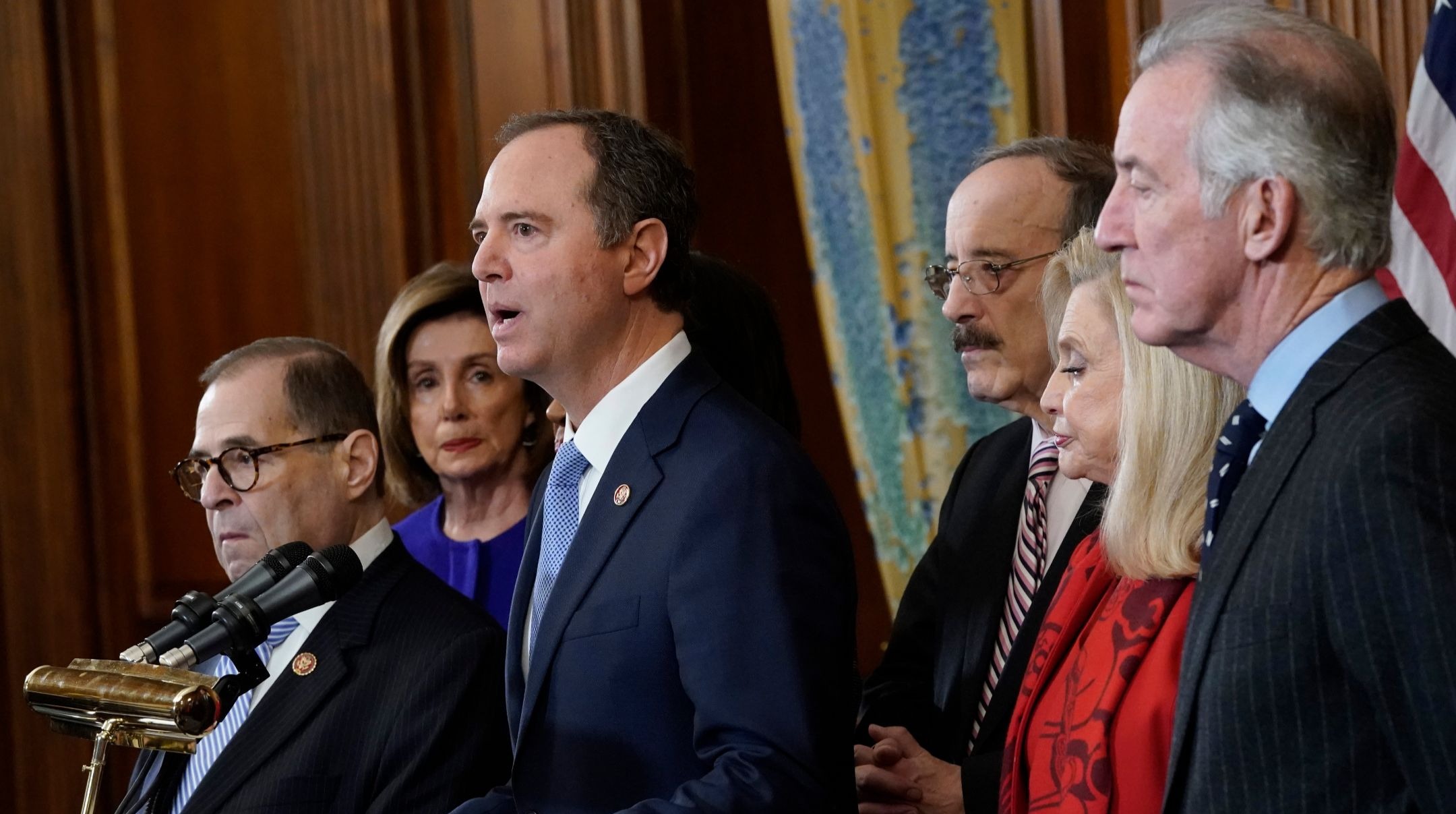

Democrats surrounded Schiff in a protective huddle as he stood in the well of the House to listen to then-Speaker Kevin McCarthy, a California Republican, read the resolution, which censured Schiff “for misleading the American public and for conduct unbecoming of an elected Member of the House of Representatives.”

He was born in Framingham, Massachusetts, and as a child, moved from there to Arizona and then to California. His family were members of Temple Sinai, a Reform congregation in the southern California city of Glendale. As an adult, he said, his family doesn’t belong to a synagogue, but they celebrate Jewish holidays and he says Jewish ethics guide him.

“‘What is required of us, but to do justice, to love mercy, and walk humbly with my God,’” he said, quoting a famous verse from the book of the biblical prophet Micah. ”I think that very much describes how I was brought up.”

Schiff becomes especially animated when he brings up how his family’s Jewish heritage inspires him. He carries his grandfather’s watch with him on Election Day as a token of his Jewish heritage and said his great regret is that his father, who died earlier this year at 96, would not live to see him sworn into the Senate.

“He loved to say, ‘from the shtetl to the Congress in three generations, only in America,’” Schiff said.

He also sees himself as continuing the tradition of former Sens. Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer, with whom he shares both Judaism and liberal politics. Boxer retired from the Senate in 2017, and Feinstein died last year. Schiff won the primary for her seat, beating out two more progressive challengers, and easily won election earlier this month against a Republican opponent.

“My father would talk often about his father and grandfather and standing on the shoulders of those who went before,” he said. “I think that ethic is very much the same as with Sens. Boxer and Feinstein.”

He said he has also carried his Jewish identity into Congress, where he and the 30 or so other Jewish Democrats, who will serve beginning next year alongside three Jewish Republicans, share a sensitivity toward protecting Jews from antisemitism. He feels anti-Jewish animosity has proliferated on the left and the right since Hamas invaded Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, launching the war in Gaza.

Schiff, at the microphone, joins with other House committee chairs and Speaker Nancy Pelosi, second from left, to announce the next steps in the House impeachment inquiry into then President Donald Trump, at the U.S. Capitol, Dec. 10, 2019. (Win McNamee/Getty Images)

“It’s as if the taboo against being overtly antisemitic has lost its power. The taboo against a lot of other forms of bigotry has lost its power,” he said.

“I think all the Jewish members feel it acutely,” he continued. “We feel, I think, very much as representatives of the broader Jewish community, that the community is more isolated and vulnerable than it ever has been.”

He recalled traveling to Ukraine while serving in eastern Europe — he said he was “struck by just how successful this annihilation of the Jewish people had been” — as well as a trip to France a decade or so ago when he spoke with a Jewish community leader about rising antisemitism there under then-Prime Minister Francois Hollande.

“‘Hollande has said some really good things and we’re getting police protection at our shul,’” Schiff recalled the Jewish leader telling him. “I remember him saying that, and I remember thinking at the time, ‘thank God I don’t live in a country like that.’ And here we are.”

He has been a fixture at American Israel Public Affairs events, and the lobby’s affiliated political action committee endorsed him this year. He said that had he been in the Senate at the time, he would have opposed Sen. Bernie Sanders’ failed effort to block weapons shipments to Israel, noting enduring threats from Iran.

“I think we should continue to work with Israel to try to minimize the civilian loss of life and do a better job meeting the humanitarian needs of people in Gaza,” he said. “We need to keep pressing Israel, I believe, on thinking about the day after this war and how we get back to a path to two states. But I don’t think cutting off support for Israel right now is the right course.”

Right now, he’s focused on what’s happening in the United States. He’s worried about Trump’s threats to install controversial cabinet picks via recess appointments, sans Senate confirmation — a test of whether the body will stand up to the president-elect. He’s also concerned about Trump’s threat of mass deportations of undocumented immigrants.

He was the top Democrat on the U.S. House of Representatives Intelligence Committee for years, and is especially worried about Trump’s pick for director of national intelligence, the Russia-sympathizing former Democratic congresswoman-turned-Trump supporter Tulsi Gabbard. He says he believes top spy talent will quit if she is confirmed.

“It’s going to be those you most want to stay who will run for the exits if they have leadership they don’t trust,” he said.

And, of course, he’s worried about Trump’s threats of “retribution” against perceived enemies — including him.

Schiff worries, he said, about Trump’s “threats to turn the federal government, the apparatus of the federal government, into a tool of revenge and destruction, including the Justice Department, which I have a particular respect for, because I came out of that department, and I venerate the department.”

He’s not too concerned, though. He trusts the guardrails that are in place in the country’s justice system.

“I think our system is pretty resilient, and I have confidence that if they ever went down that road, they would run into a lot of legal constraints,” he said.

And he’s maintaining his sense of humor. During the 2019 impeachment drama, he recalled, The Washington Post profiled him and noted that years earlier, as an assistant U.S. attorney in Los Angeles, he shopped a screenplay around Hollywood, a courtroom drama.

“This profile came to Trump’s attention, because for a little while after that, he referred to me as a ‘failed screenwriter,’” Schiff said. “I told my staff, I said, ‘He doesn’t realize what a great favor he’s doing me. Half of my constituents are failed screenwriters.’”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.