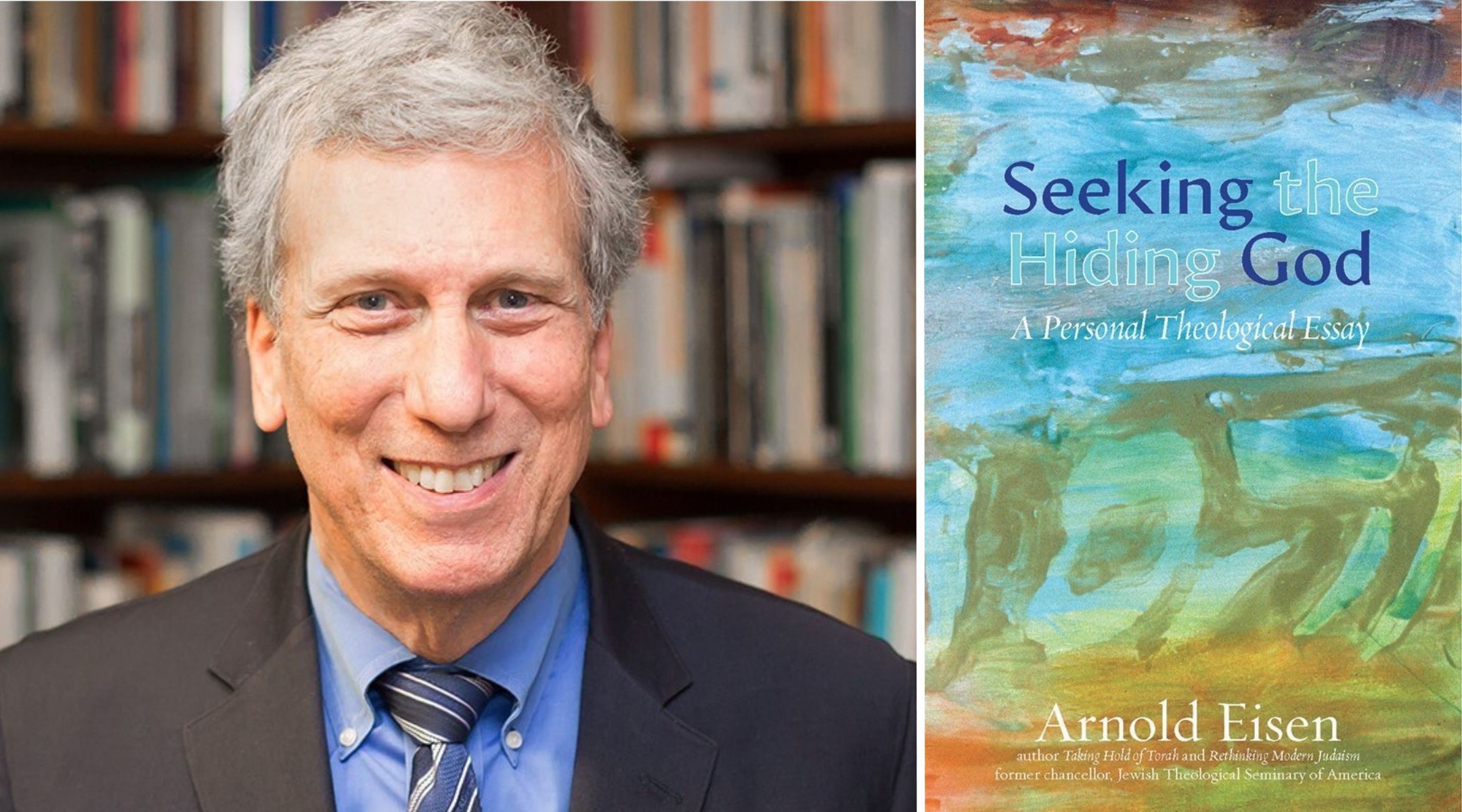

After stepping down as chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary in the spring of 2020, Arnold Eisen found himself with the time and motivation to think about a big question he’d long put off as the leader of the Conservative movement’s flagship university and, before that, as a professor of Jewish culture and religion at Stanford University.

“When my friends asked, ‘Arnie, why is it that you have faith and we don’t?’ — I tried to figure out what experiences in my life made me open to the possibility of faith,” he said last week.

He answers their question in a new book, “Seeking the Hiding God: A Personal Theological Essay,” in which Eisen describes what he believes about a God whom he acknowledges to be elusive, if not unknowable.

The book is a professional departure for Eisen, whose previous books examined the interior lives of American Jews and and the classics of modern Jewish thought with the forensic gaze of an academic. It is also a personal departure for an observant Jew who nonetheless shared the American Jewish allergy to what he calls “fervent God-talk.”

“I was writing scholarship about other people’s Jewish thought for something like 40 years, but I always somehow avoided, as many scholars do, facing the questions of what I actually believe,” said Eisen.

Begun during the COVID lockdown and finished after Hamas’ 2023 attack on Israel, the book synthesizes the thoughts of some of Eisen’s intellectual heroes, including the Conservative movement theologian Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and the German-Israeli philosopher Martin Buber.

From Heschel he learns that Judaism is a call to action; from Buber, that miracles aren’t evidence of the supernatural, but an invitation to “abide in the astonishment” of creation. In our interview, Eisen said his aim is not to prove to the reader that God exists or that God is good, but to offer one Jewish believer’s account of how Judaism makes sense of the world.

Eisen grew up in suburban Philadelphia, where his family attended the Conservative synagogue Temple Emanu-El. “I had my mother lighting candles every Friday night. I had my father saying the priestly benediction, putting his hands on my head and crying,” he recalled. Those powerful emotional bonds, he said, shape his theology. ”These memories sustain me. Not every one of us has that. One can come to God and Jewish tradition or any religious tradition later in life, but it makes it easier to have this kind of background.”

Eisen earned a B.A. in religious thought from the University of Pennsylvania, a BPhil in the sociology of religion at Oxford University, and his PhD in the history of Jewish thought from Hebrew University.

Prior to becoming JTS chancellor in 2007 — the first non-rabbi in the role — he served on the faculties of Stanford, Tel Aviv and Columbia universities. He remains a full-time member of the JTS faculty.

The book, he said, is also meant to close the gap between the academy and everyday life.

“I wanted to give an account of what this Jew believes at this point in his life, and hope that that will be meaningful to my readers and will engage them in the project of thinking about this for themselves,” said Eisen, 73.

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

You are a scholar of American Judaism and the history of Jewish thought, and for 10 years you were a chancellor of a university, albeit one that also ordains rabbis. Why did you feel the need to write a book of theology?

When I was chancellor of JTS, working six long days a week, I had every excuse in the world to avoid this. But I recognized, even before I stopped, that the first project I wanted to take on when I stopped being chancellor was this. I wanted to try to do an account of what I myself believed about God.

And then I had a sabbatical year off, and it turned out to be the COVID year, and it was also the year I was about to turn 70. So there was this confluence of circumstances that led me to sit down and think hard and reflect.

Eisen, then chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, speaks at the 121st commencement exercises, May 21, 2015. (Via YouTube)

I am going to ask you something that may be unfair, but I am thinking of an old radio program, “This I Believe,” where guests had to lay out their philosophies in five minutes. Do you have the elevator pitch version of your theology?

I don’t have that pitch, but let me start with the title: ”Seeking the Hiding God.” When I say the hiding God, the dominant theological issue in Jewish life for the last couple generations has been the Holocaust, and one of the major theological responses to the Holocaust is what we call [in Hebrew] “hester panim,” the hiding of God’s countenance, which is a phrase from the end of the book of Deuteronomy. And some Jewish thinkers apply this not only to reactions to tragedy, but, for example, to the condition of modern life. Martin Buber writes a book called “Eclipse of God.” Or the Orthodox thinker Eliezer Berkowitz, who says that this is a permanent condition of human life: that if God was so close to us that we could grab God at every opportunity, there wouldn’t be room for us to be free human beings with initiative in action and thought. So God needs to be far away, as it were, for us to be who God wants us to be.

I had the sense for a long time that if I was really a better person or more devoted to my Judaism, or spent more time in prayer, or more time thinking about God, that I would be granted a much more robust set of religious experiences, and I would be much more certain about this God that our tradition teaches us can be encountered. And what I came to recognize is that my sporadic, momentary, ephemeral encounters with God were far more typical than not, and that many Jewish thinkers testify that this is precisely the kind of experiences that they’ve had as well.

That’s the “hiding part.” But you also write in the book that if God’s countenance is hidden, God’s intentions are not. You write how Buber said that human beings cannot know when or how God acts to punish or reward, but they can heed the prophets who said they should pursue “righteousness and loving-kindness to the maximum extent possible under the circumstances.”

If there’s a mantra in the book, it’s Deuteronomy 29:28: The mysteries belong to God, but the revealed things are given to us and to our children to live a life of mitzvah, and we can have this good life.

In that regard, a word that keeps coming up in your book is “action,” and how human action is key to bringing out redemption, or realizing love in the world, or righting injustice. That seems key to your theology.

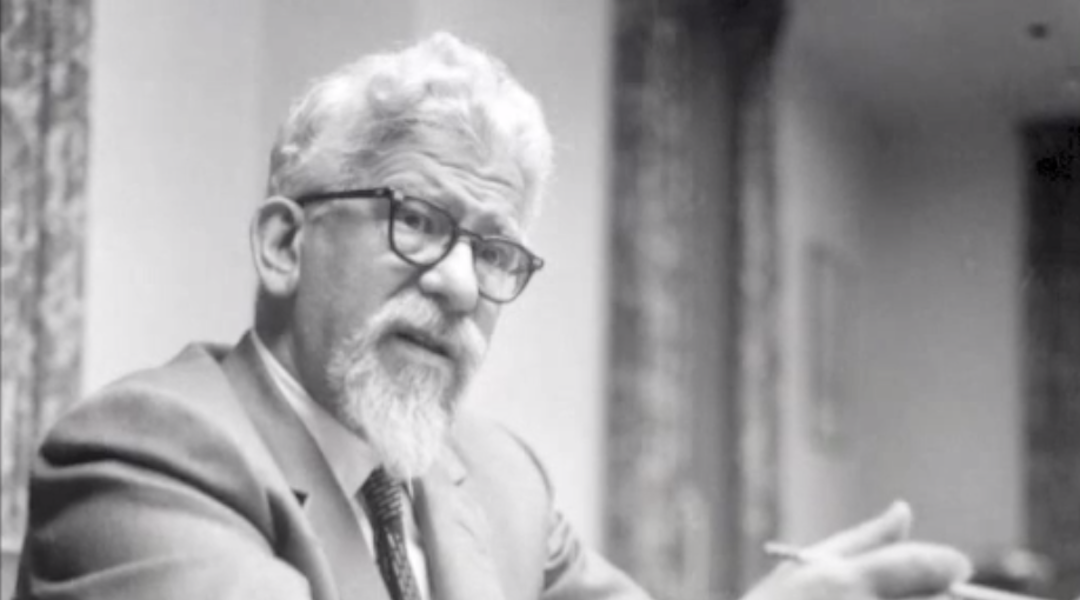

Central, absolutely central. I can’t imagine belief in God is meant for us to secrete ourselves away and to meditate and contemplate our own enlightenment. That’s not what this tradition says. I’m a child of the ’60s, and I saw that political action and social activism made a difference for good in the world. And in Heschel I had in front of me this personal example, even before I met him: I’d read his books and admired his work, and then I got to meet him, and he just left me convinced that that piety does not stop in the synagogue. You have this famous paragraph in his book “God in Search of Man” in which he writes that Judaism doesn’t take a leap of faith. It takes a leap of action. And that paragraph means everything to me.

I think many Jews appreciate action — home rituals like the Passover seder, or acts of loving-kindness or social action expressed as tikkun olam — but don’t understand the point of prayer. I know it’s a vast question, but what do you think is happening when you are in prayer?

I can say that for me, there isn’t only one thing that’s happening, and it doesn’t always happen. Prayer in Judaism is not just petition, which is what the English word sounds like. It’s not just asking for things. It could be saying thank you, or saying hello, or “here I am, God, I’m happy you’re in my life,” or “I’m sorry.” And for me, the hope is to have a sense of being fully myself. I’m trying my best to stand before God, even when it’s really hard to imagine this God that I want to stand before. I’m really standing before myself and that which is most precious to me in the world, and trying to use my time in the world well, and stepping aside from all the distractions of normal life and focusing inwards. And by focusing inward, you somehow connect to God.

But what I should declare in this moment, since you asked in this direct way, is that unlike some Jewish thinkers like Mordecai Kaplan [the founder of the Reconstructionist movement], who did not believe in a God who can hear prayer, I’m much more open-minded about this. I would not have the chutzpah to make a declaration about what God can and cannot do. I think Kaplan was anachronistic there and that you can’t say what any modern person can believe. And I testify in the book that I myself have had experiences where I feel my prayers have been answered. What that means from God’s side, I don’t know.

I know lots of people who can’t bring themselves to engage in anything like what we call prayer, because they can’t tell it to their minds, and so they don’t try. And what a shame that is. Because if one opens oneself to this possibility of encounter with the divine, the transcendent, whatever you want to call it, then it may happen.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907-1972) convinced Eisen that “piety does not stop in the synagogue.”(Screenshot from YouTube)

You write that when you teach American college students about Buber and Heschel, they ask “why these thinkers needed to talk about God so much when what they really cared about was ethics.” It’s the classic question: Can’t you be good without God, and what does belief in a supreme being add to the equation?

Yes, one could have a good life without God. And yes, one does not have to be a Jew to have a good life or whatever afterlife is promised to us. But if this is an eternal human search, and if you can have the grace of encounter with God — if that is possible, why would you possibly want to live without that? I’m not preaching to anybody. But what I am saying, in all humility, is that I cannot imagine my life without the Torah and without the quest for God or the Sabbath any more than I could imagine my life without my wife and my kids and my good friends — without love. It’s just part of the basic operating equipment that makes me the person I am. The great theologian Franz Rosenzweig taught that we’re not here to prove anything. We’re here to testify.

I want to ask you to put on your institutional hat for a second, and ask from that perspective why so many American Jews might be resistant to the transcendent. According to Pew, U.S. Jews are far less likely than the public overall to say that religion is important in their lives. You write in your book, “Jews engage in sustained or fervent God-talk much less than Americans of other faiths.” As someone who was in the business of training rabbis for 10 years, do you see that as a failure of the synagogue or other institutions?

Because of my background in modern religion in general and in modernization, and my studies of sociological theory and sociology of religion, I’m acutely aware of how difficult faith is in the modern world, and especially for Jews in America, where we are such a distinct minority. And if you’re a Jew, you’re exposed to this dominant secular language on the one hand, and Christian language on the other hand, which is, chances are good, evangelical or fundamentalist. And the Jewish language you hear from other Jews is a very ultra-Orthodox language, which may not suit you, and you may become convinced that that’s the only language there is. So we have failed them, yes, but the culture is such that it makes it really hard not to fail.

I had the experience again this past weekend speaking at a synagogue in San Diego, and having to tell committed Jews that the theology which says God is responsible for everything that happens in the world is by far not the only Jewish theology there is. One does not have to believe that the Holocaust happened with God’s acquiescence, let alone with God’s active participation. And [the audience] was simply not aware of all these options. They’ve never been exposed to them, not as adults and not back in Hebrew school. That, to me, that’s tragic.

I want to ask specifically about the Conservative movement, because you headed one of its flagship institutions. First, is there something capital-C Conservative about your theology?

No, I didn’t write the book denominationally. I am a lifelong Conservative Jew, and my theology is certainly compatible with that. But I am a Jew first and foremost, and the dominant resources in my book are the Torah and the siddur and the rabbis of old, and modern Jewish thought of all stripes. There’s [Modern Orthodox Rabbi Joseph] Soloveitchik is in this book, along with Heschel, and [Reform Jewish philosopher Emil] Fackenheim, Kaplan. Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, Reconstructionist. It’s not a Conservative book.

More and more, we may affiliate with a particular synagogue, but we’re not necessarily in our thinking denominational. I cannot be ultra-Orthodox because I’m an egalitarian Jew, but beyond that, there’s meaning to be found in every single denomination.

The other question I want to ask about the Conservative movement is its relevance. In sheer size, influence and market share it is not the central movement it was a generation or more ago. In what ways did you confront this challenge as chancellor, what changes did you hope to bring about, and did some of that thinking have anything to do with the ideas in the book?

Let’s understand what conditions fostered the growth of Conservative Judaism in the ’30s through the ’60s, which were sociological and economic and political. This was the right movement with the right message for the time. And then I think the movement made two key innovations — the first, of course, being egalitarianism regarding women, and the second, which I had a direct role in, which was opening itself up to LGBTQ individuals in a full way. Had we not done either of those things, the movement would not be even as successful as it is today. It would not be a live movement.

But these are very difficult times, and I think that we’re not doing so badly. Yes, the number of people who say “I’m a Conservative Jew” is much less than it used to be. I think that is primarily because Conservative rabbis will not perform intermarriages, and if you can’t have a Conservative rabbi [officiate] your wedding and you’re intermarried or the child of an intermarriage, you’re not going to say, “I’m a Conservative Jew.” But the membership statistics [as opposed to self-identity] are not that bad. The Reform movement is several percentage points above Conservative, Modern Orthodoxy is still around 3 to 4%, which means it’s not growing by leaps and bounds, and ultra-Orthodoxy is growing, yes, but only by virtue of birth rate. So we in America have a problem. All of us have a problem. Yes, the middle is shrinking, but Judaism is shrinking and religion is shrinking. If less than 40% of American Jews are affiliated with anything Jewish, where are we with this community? How can we be a stronger community? How do we get people in the door? This is our problem.

The Jewish Theological Seminary in Manhattan. (JTA)

So since you wrote a book about theology, not institutional reform, I want to ask how your ideas about God and practice and action might address the questions you just posed.

When it comes to what you do with the people when they’re in the door, I have strong opinions, and they are directly related to the book. The Yom Kippur chapter, for example, explains how, on the one hand, I love Yom Kippur. I love the music. I love the liturgy. I love the experience of 25 hours with my community. And yet I can’t stand a lot of the liturgy. I disagree profoundly with the leading theme. I don’t think God is there deciding who lives for another year and who doesn’t, and that’s the central theme of the day.

So how can you have a congregation which gets together for 25 hours without giving people the chance to sit around small tables, when they’re most open, perhaps most thoughtful, and discuss honestly with one another what they actually believe about these things? I urge every single rabbinical student I come in contact with, do not do the Unetaneh Tokef prayer [“who shall live, and who shall die…”] without contextualizing it. Do not let people believe that if they walk out of synagogue and get hit by a car, God has decided to get them hit by a car.

The final thing I’d say about this is that we’re in a difficult time. Because of AI, people are going to lose their jobs, and people who have jobs are going to be [doing something] completely different than they were before. And it’s scary because of climate change: The catastrophe is imminent, and at some level, we all know this. The Hamas attack on Oct. 7 made tragedy and fear visceral for many Jews, and some of them flocked back to Jewish communities. They want contact with their tradition. They’re looking for meaning. It’s a moment of crisis, but it’s a moment of great opportunity, and we just need to be creative.

There are dozens of really skillful clergy and educators in this country who are doing this all the time, and it can be done. It’s just not widespread enough. We’re not always as creative as we could be, but I’m convinced that the possibilities are there now.

I wanted to ask about Israel: How does it fit into your theology? You write that “God is counting on human beings to write the next chapter of history,” which would suggest that you find it difficult to believe that Israel’s creation and its well-being are in the hands of a God who intervenes in history.

Israel is crucial to my Judaism, but it’s not because God is doing this. I don’t know what God is doing there. I pray that it will turn out to be the beginning of the flowering of our redemption. But who knows?

My teacher David Hartman [the late Israeli-American philosopher] taught me and many other people that the theological model for Israel is not Exodus, where God split the Red Sea, but Sinai, where what is important is that Jews try to live up to the responsibilities of the Covenant, and that they translate the ethical principles pronounced in the 10 Commandments. Israel opens up new possibilities for covenant. What can we do now that we’re a majority responsible for non-Jews as well as for Jews, Jewish healthcare policy, Jewish foreign policy, Jewish educational policy, etc.? It’s a great opportunity to see what mitzvah can mean in the modern world. In a place where Jews have a majority, it’s not about God intervening in history.

My last question is going to be the classic one that I think everyone who tackles theology has to talk about, which is your views of the afterlife. Do you believe in one, and how does death figure into your thinking about God and your purpose in life?

I can’t be like Moses Mendelssohn in the 18th century, the great Jewish thinker, and prove to you logically that there’s an afterlife where the good are rewarded and the evil are punished. I can’t do that, but what I can do is witness to the kind of faith that I’ve managed to acquire, which holds out the possibility that death is not the end of everything. Genesis teaches that Sarah’s life continues with her children, and Jacob’s life continues with his children. And I certainly think that’s true, but it’s not only in children, and it’s not only in students, and it’s not only in the legacy we leave behind us. It could well be that there’s some immortality for the person.

When I was at Stanford and the Dalai Lama came to speak, I was really struck by the fact that he fervently believes that our beings do not cease to be when we die. So we’re in good company. I think that we should not give up on this, and that theologians, if they can encourage this kind of hope, they should, and that’s what I try to do in the book.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.