The Jewish people have long taken pride in their moniker, People of the Book. But Jews are also people who dance — and not just at weddings and bar or bat mitzvahs, or on holidays like Simchat Torah.

Like many other communities, Jews dance to foster and build community, and to come together for spiritual, social and recreational occasions. They dance to express unity and individuality, their peoplehood and creativity. Simply put, they dance to belong.

An illuminating exhibit at the venerable 92nd Street Y, New York — which has been celebrating its 150th anniversary this year, rebranded as 92NY — explores the Jewish community’s rich movement traditions. Drawing upon 92NY’s extensive archive of photos, programs, posters and more, “Dance to Belong” tells the story of the vibrant and creative community Jews built and uplifted through dance.

Among the many treasures on view are a 1915 photo depicting a dance class with lines of women clad in white tunics, their arms waving, a la Isadora Duncan; a 1940 poster advertising an evening by ballet and Broadway choreographer Agnes de Mille, featuring maverick modern dancer Sybil Shearer; and a 1943 playbill for a concert starring flamenco greats La Argentinita and Jose Greco.

Dance classes continue to be an important aspect of the 92nd Street Y’s programming. (Christopher Duggan)

“I was asked by Jody Arnhold, who is the chairwoman of the board [of 92NY], to curate a show on the 150th anniversary that would celebrate dance at the Y,” said cultural historian Ninotchka Bennahum, a professor of theater and dance at University of California Santa Barbara and a co-curator of the exhibit. “I knew that the Y was a social justice warrior [in] its commitment to working artists, to Jewish dance artists, to BIPOC artists, to immigrant artists. It was a 150-year story.”

Dance has been part and parcel of 92NY since it opened its doors in 1874 as the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, founded by a group of German Jewish businessmen to serve the social and spiritual needs of the burgeoning American Jewish community. First located on West 21st Street, then 42nd Street, the organization moved uptown several times to 65th Street in 1899, then 92nd and Lexington the next year. In 1930, the current digs at 92nd Street and Lexington Avenue opened.

According to Bennahum, 92NY became an essential meeting space because Jewish immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, like Jews today, weren’t necessarily affiliated with synagogues or other Jewish organizations, nor did they always speak the same language or come from the same socio-economic class. The 92NY served as a crossroads for Jews across religious, national, economic and social identities.

“Think of the people coming [to New York], not speaking English, feeling that they live in translation,” Bennahum said. “What do we carry with us in our body? Dance is shelter … which required no translation.”

“We’re talking about Ukrainian, Lithuanian, Polish, Russian and Mizrahi Jews meeting in intercultural exchanges, or, in the words of [dance scholar] Hannah Kosstrin, who calls these many intercultural exchanges ‘kinesthetic peoplehood,’ the migration of Jewish cultures and people — Mizrahi, Ashkenazi, Israeli, American, Palestinian, Turkish — from the Sefarad and Eastern Europe to the U.S.,” she added.

In addition to providing New York’s Jews a place to dance socially, 92NY offered its stages and studios to a cadre of early modern dancers. The Harkness Dance Center, which opened at 92NY in 1935, became a prime space where eminent modern dancers including Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey and Paul Taylor presented their works. Furthermore, when doors were closed to African-American, Asian-American, Latinx and Native American dance artists, 92NY welcomed them.

The exhibit, which opened in March and is on display in the Kaufmann Concert Hall lobby and adjacent Weill Art Gallery through Dec. 31, traces the myriad ways dance has shaped the venerable cultural institution. Featuring video panels designed by Jeanne Haffner of Thinc Design, “Dance to Belong” moves across five major themes. The first focuses on education and community building, and includes photos of children’s classes; senior adults standing at a ballet barre, legs lifted; and Israeli folk dance sessions led by Fred Berk, founder of the Y’s Jewish dance division in 1951, who introduced Israeli folk dance to Jewish communities across the U.S.

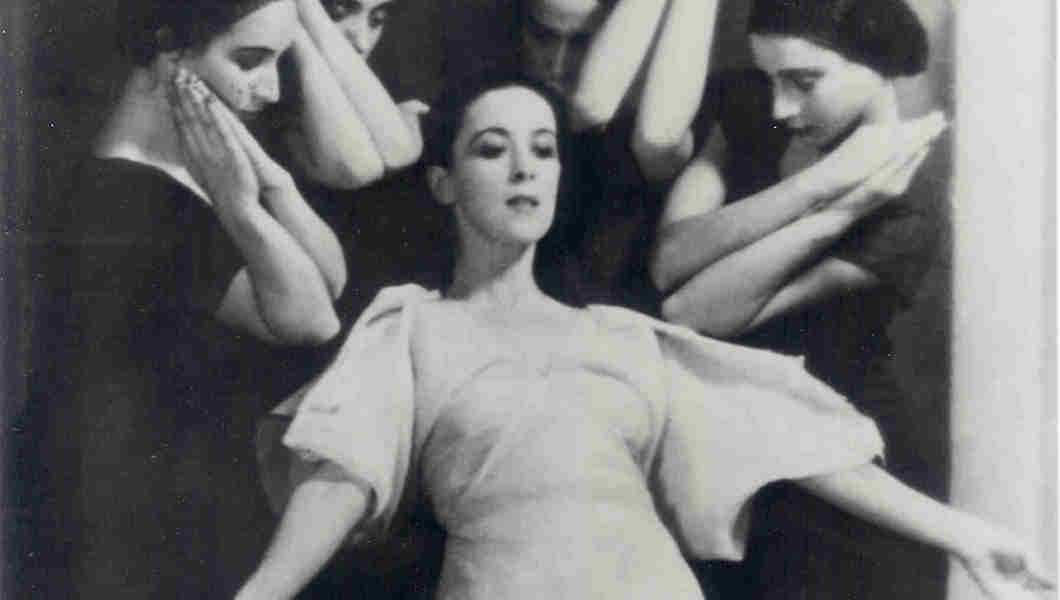

Modern dance pioneer Martha Graham, pictured here in the 1930s, was a mainstay at the 92NY. (Courtesy)

Other sections include “Black Moderns,” which spotlights the 1960 premiere of a then-unknown multi-racial company helmed by the now-renowned Alvin Ailey, whose choreography examined challenges of being Black in America, and “Dance As Political Manifesto,” which traces how Eastern European Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side used dance and choreography as protest, and how successive generations followed suit.

Dance continues to thrive and evolve at 92NY; upcoming performances include former street-dance krumper-turned-ballet dancer Babatunji Johnson on Dec. 14 and, on Jan. 11-12, 2025, “A Dance of Hope” from Carolyn Dorfman Dance that draws upon Dorfman’s “rich Jewish legacy.”

“This exhibit confirms the Y’s longevity and significance of community-based dancing not as something tertiary, but as something primary,” Bennahum said of “Dance to Belong,” emphasizing that the institution has “creat[ed] a continuous space for dance in always giving sanctuary to contemporary artists, in believing in Jewish dance artists and in believing in all artists.”

“Dance to Belong” is on view at the Milton J. Weill Art Gallery and the Kaufmann Concert Hall lobby at the 92nd Street Y (1395 Lexington Ave.) through Dec. 31. Admission is free.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.