By the time I was 76, I thought I knew my father well. He had been an open person who had spoken about his life and hadn’t avoided (as many of my friends’ parents did) talking about the difficult years of the war.

I also knew that loved the desert near his California home — that was where he would go when he and my mother had a weekend away. But I never appreciated what the desert meant to him.

My father had an unusual life, so one day I decided to sit down and write a short essay about him. I started to write that he was born in Warsaw, but suddenly I wasn’t sure. What about that story he told countless times of coming from Russia to Warsaw as a small child, in a wagon with his family, traveling through woods full of scary wolves? Maybe he was actually born in Russia and grew up in Warsaw.

He had written a memoir late in his life that I had read and then stuck on a shelf and forgotten about. Reading it again I found the answer to my question as well as all sorts of wonderful stories. Instead of writing an article, I set out to write a book.

My father, Rafał Feliks Buszejkin, was indeed born in Warsaw in 1912. His adventures began when he was 3 years old and his family left Warsaw to escape the Germans and went to live in Moscow. When he was 5 they moved back to Warsaw to escape the Russian Revolution.

He was hardly a stereotypical Eastern European Jew of the early 20th century: His family was bourgeois and not observant; he spoke Polish with his parents rather than Yiddish; the only Hebrew he knew was what he memorized for his bar mitzvah. He boxed, raced bicycles and got into fights; rather than attend his last year of high school, he played poker, made mischief with a group of youths, and failed the year; he never liked working indoors and was happy doing physical labor.

The author’s father Rafał Feliks Buszejkin, in long pants, poses with members of Maccabi, the sports club he founded in Algeria in the early 1930s. (Courtesy Dvora Treisman)

Successfully repeating the last year of school, in fall 1931 he went off to university to study medicine at the University of Montpellier in France. It went well until they had to cut up a frog in the biology lab, and he decided medicine was not for him. The next fall, he announced to his parents that he would be going instead to the Institut Agricole d’Algérie in Algiers.

Happily studying agronomy, he explored Algiers and Algeria, and spent time with two new friends, one from Belgium and the other from Laos. One day in late spring he came down with an inflammation of the joints that left him immobilized. He was advised to go to Biskra, a posh oasis town known for its curative facilities, 250 miles away, on the northern edge of the Sahara.

His two friends hoisted him onto an old, overloaded bus where, once seated, he couldn’t move and thus couldn’t relieve himself. Dozing off, he suddenly recognized the familiar scent of gefilte fish! He looked around and saw an Arab who was eating what seemed like this Jewish specialty. He asked the man (in French) where he had bought his lunch. The man said that his wife made it and offered Dad some.

He and the man started to talk. The man asked him the usual: Where are you going? What do you do? Dad explained. The man then told him that he was a Sephardic Jew and he worked as a tour guide in a big oasis at the foot of the Atlas Mountains — Bou Saâda, 100 miles west of Biskra.

His new friend invited him to come there and be cured; it would be far cheaper than the fancy spa. Dad accepted and spent 45 minutes a day buried in a shallow grave in the hot sand with his head shaded by an umbrella. After five days of this torture, he was cured.

Soon after, he commented to his friends that they spent a lot of time sitting around sipping tea, eating exquisite pastries and getting fat. Would they like to start a sports club and get in shape? Not only his friends, but more than half the village, both Arabs and Jews, liked the idea. In three days they raised over 300,000 francs and set out to buy equipment and have uniforms made. The uniforms were white shorts and blue sleeveless shirts with a Magen David on the front. A local lawyer drew up the bylaws and they named the club Maccabi.

Besides coaching the boxing team, during his time in Bou Saâda, Dad rode beautiful Arabian horses, was invited to feast with a sheik, and learned to drive a car when it was time to return from a banquet and all his friends were too drunk to drive. My father left Algeria suddenly in May 1933, called back home when his father went bankrupt.

After his return to Warsaw, Dad worked as a cattle and pig buyer for a big meat packing company. After marrying my mother in 1938, they left Warsaw a few days after the Germans invaded in September 1939. They spent part of the war in Siberia and the rest in Dzhambul, Kazakhstan, where he supervised the agricultural production of five kolkhozes, or collective farms, until they were repatriated after the war ended. When they arrived back in Warsaw they found that everyone in their two families had been murdered by the Nazis.

They lived in Nice while awaiting visas to immigrate to the Dominican Republic where he farmed at a Jewish collective settlement in Sosua. That is where I was born. After two years, we left the Dominican Republic to go live in the United States where more adventures of a different nature awaited.

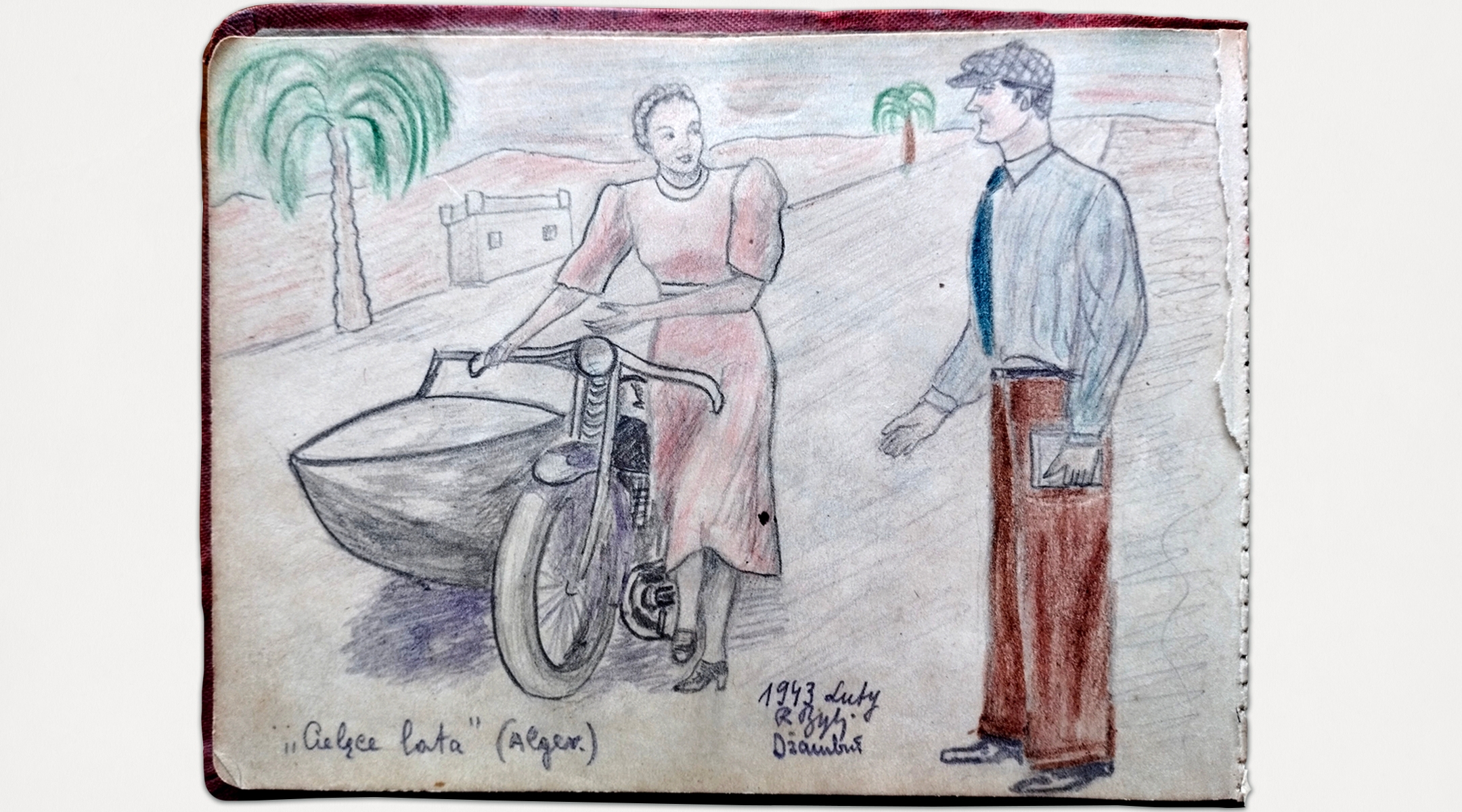

As I was finishing my book, I remembered a small, faded red notebook that I had tucked away years ago in a drawer and went to find it. It was nothing special, old, faded, and there wasn’t much in it, just some drawings and some writing that I couldn’t read. There was a shopping list and the lyrics to a popular song. The drawings were done in colored pencil; three were by my mother and three by my father. Each drawing was signed, titled and dated “Dzhambul, February 1943.”

One drawing was of a woman, nicely dressed in European clothes, holding the handlebars of a motorcycle with a sidecar, and talking to a man at the side of a desert road with two palm trees behind them. It was by my father. At the bottom he had written “Cielęce lata” and “Alger.” Alger is Algiers in French, but what did the Polish say?

I found out that “Cielęce lata” means “calf years” and has the same meaning as “salad days” in English. In the middle of the war, in far off Kazakhstan, he was remembering the halcyon days of his youth in Algeria. That is when I realized that through most of his life, his favorite stories tended to be from his time in Algeria, even the embarrassing one when the javelin he threw pierced his friend’s leg. It also explained why he always wanted to go to the desert for weekends, and why it was to the desert that he went to spend his last years.

Parents have stories to tell, but we don’t always pay attention; sometimes we don’t listen at all. Sometimes we listen, but we don’t get the meaning. Eventually it becomes too late. No more stories, no more opportunities to ask questions. I was lucky that my father wrote some of his life stories down so that someday I might pay attention. And yet it was that small pencil drawing that explained what words didn’t.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.