Mel Brooks, who mocked Adolf Hitler in his 1967 black comedy “The Producers,” has always made the case for satire as a weapon against tyranny.

“You have to bring him down with ridicule,” he told “60 Minutes” in 2001. “It’s been one of my lifelong jobs — to make the world laugh at Adolf Hitler.”

Of course, Hitler was long dead and there were 6 million fewer Jews on the planet when “The Producers” came out. Before and during World War II, satire proved a futile weapon against the Fuhrer: Charlie Chaplin made “The Great Dictator” in 1940, similarly reducing Hitler to a buffoon. But by the time the movie premiered that October, nearly 3 million German troops had smashed into France, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

The futility of satire was on my mind when, on the Thursday after Election Day, I toured a new exhibit at the Jewish Museum on the Upper East Side in Manhattan. “Draw Them In, Paint Them Out: Trenton Doyle Hancock Confronts Philip Guston” features two artists, one Jewish, one African-American, whose work wrestles with racism, white supremacy and antisemitism.

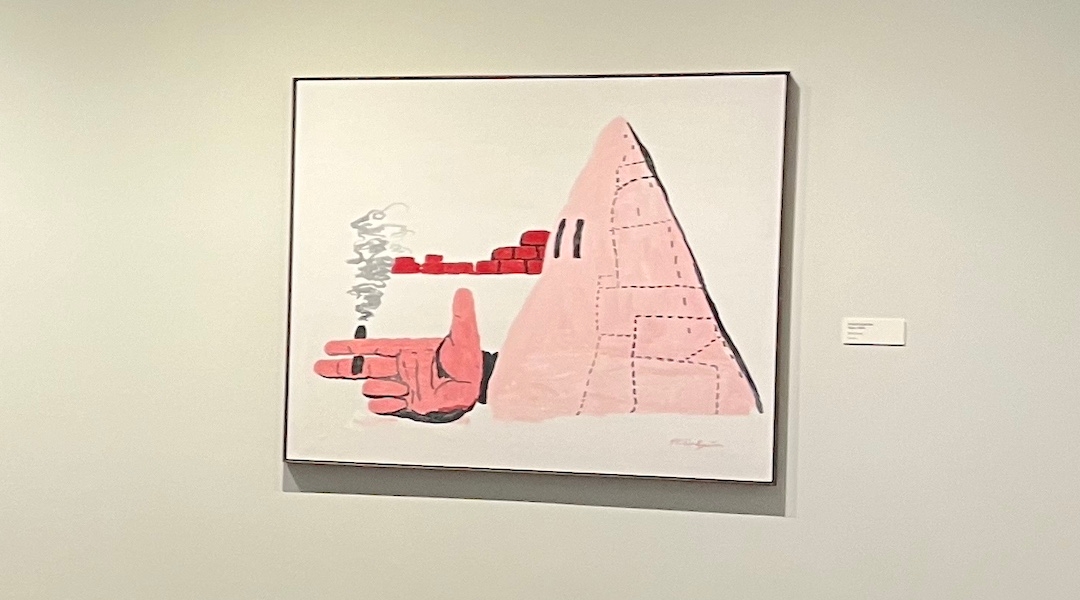

Philip Guston, born Phillip Goldstein in Montreal in 1913, was inspired by the ferment of the 1960s to create a series of cartoonish paintings featuring hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan. In these almost cheerful paintings, the frightening avatars of white supremacy look like costumed children out of a Charlie Brown comic (or, more accurately, from “Krazy Kat,” a popular comic strip in Guston’s youth).

“These buffoonish Klansmen still today are a real rebuke, I think, to bigotry in all its forms,” curator Rebecca Shaykin, who organized the exhibit, said at the press opening. “They’re still just so incredibly powerful.”

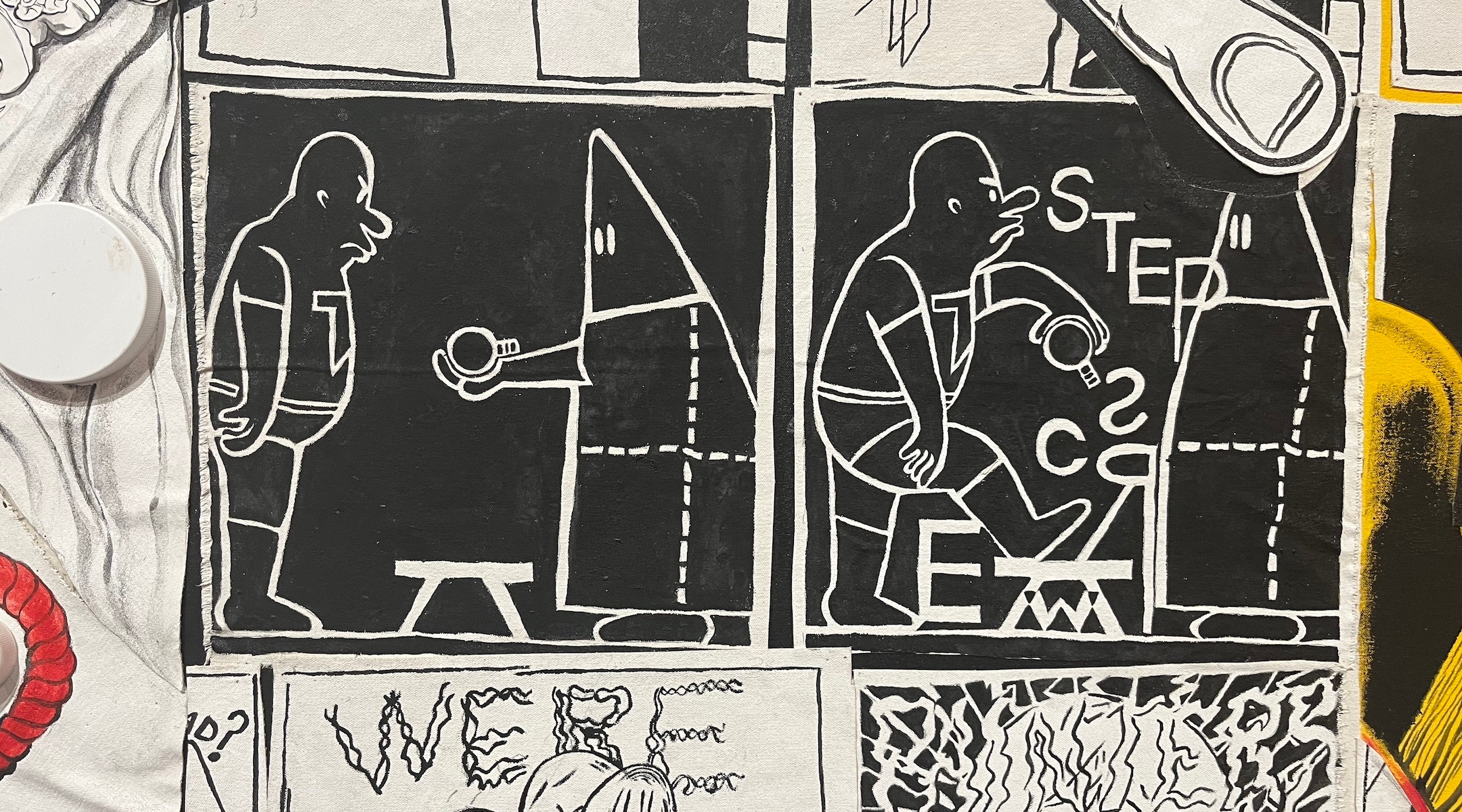

About a third of the gallery is given over to Guston’s Klan paintings, as well as some of his earlier work. The rest features riotous paintings, cartoons and a film by Hancock, a Texas-born artist who was a child when Guston died in 1980 in upstate Woodstock, New York. Many of Hancock’s paintings directly quote Guston’s Klansmen: They are in painting after painting featuring “Torpedoboy,” a sort of Black superhero who Hancock considers his alter ego. The Klansmen try to lynch Torpedoboy; he fights back and, in one painting, appears to drive a spike through a Klansman’s head.

In the exhibition catalog, Hancock describes what attracted him to Guston’s Klan paintings. “I fell in love with the forms, and how he used comedy to take the wind out of the sails of the KKK,” says Hancock. “He helped me understand where I could take” my own characters.”

“Draw Them In, Paint Them Out: Trenton Doyle Hancock Confronts Philip Guston,” at The Jewish Museum, features works by Guston, left, and Hancock, right. (JTA)

Whether audiences appreciate the comedy depends on their sensibility; remember, it was decades before “The Producers” lost its “notorious” label and became a beloved institution, at least in its adaptation as a Broadway musical. For some, the Klan paintings by both artists could be triggering. In 2020, at the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, four major museums certainly thought so, and postponed a comprehensive survey of Guston’s work. They explained that “the powerful message of social and racial justice that is at the center of Philip Guston’s work can be more clearly interpreted.”

When the exhibition did open at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 2022, the museum offered a pamphlet from a trauma specialist and a detour allowing visitors to skip the Klan-themed works.

The Jewish Museum seems unfazed by that controversy. When I asked Shaykin about it she said the Guston-Hancock show had already been percolating when she learned of the postponement controversy. “It just made it more imperative, I think, that we bring Guston into the present moment and pair him with a contemporary artist,” she said. The only suggestion that images might be controversial is a sign outside the gallery, warning that the exhibit contains “explicit language” and “depictions of violence and lynchings.”

James Snyder, director of the Jewish Museum, also said the exhibit is right for the political moment.

“We don’t do politics,” he said at the press preview, “but if you think about what happened the other day in the election, and where we actually really need to go, this show could not be more timely.”

What happened, of course, was the election of Donald Trump to a second, non-consecutive term. And if ever there was a rebuke to the power of satire, it is Trump. Trump was a nightly target of nearly all the late-night talk shows, where he was mocked as a racist, a would-be authoritarian, a grifter and a vulgarian. With just a week to go before the election, Jimmy Kimmel made a direct appeal to Republicans to reject Trump, calling him “the exact meeting point between QAnon and QVC.” For years Stephen Colbert wouldn’t even say his name.

A detail from “Step and Screw Part Too Soon Underneath the Bloody Red Moon” (2018), by Trenton Doyle Hancock, depicts the artist’s alter ego, Torpedoboy, left, and a figure based on Philip Guston’s images of Klansmen. (Collection of Mandy and Cliff Einstein, Los Angeles)

Deserved or not, the jokes about Trump didn’t make a dent in his popularity — and perhaps they only added to it. In a recent episode of his podcast, “Revisionist History,” Malcolm Gladwell talks about the “satire paradox”: the idea that satire, by making the targets entertaining, actually makes them more sympathetic. He quotes Jonathan Coe, a British writer who argued in a 2023 essay that “laughter is not just ineffectual as a form of protest, but that it actually replaces protest.”

“Laughter, in a way, is a kind of last resort,” Coe tells Gladwell. “If you’re up against a problem which is completely intractable, if you’re up against a situation for which there is no human solution and never will be, then OK, let’s laugh about it.”

Not that Guston and Hancock are not deadly serious in their aims. The art is provocative and appropriately disturbing. The exhibit suggests that Guston, who changed his name from the identifiably Jewish “Goldstein” in 1935, later felt guilty about abdicating his identity — and as a result felt complicit with the Klansmen who sought to erase both Jews and Black people. “They are self-portraits,” Guston once said of the Klan paintings. “I perceive myself as being behind the hood.”

Hancock’s seemingly humorous works are also working through extremely grim themes. The Klan was active in his hometown of Paris, Texas, and in 2021 a KKK chapter planned a “White Unity Conference” there before it was blocked by the city council. Born in the mid-1970s, Hancock acknowledges in the catalog that he had benefited from the “heavy lifting” done by his elders in the Civil Rights Movement. But as a Black man and Black artist, he couldn’t ignore the legacy of racism. “It wasn’t until I was much older that I started to peel away those layers, or have them peeled away for me,” he says.

That’s why the most effective works in the exhibit aren’t satirical. At all. They include early work by Guston, who already as a teenager was depicting the Klan and lynchings in the social realist style of the day. Nothing about these dark, frightening images is cartoonish or ambiguous.

And perhaps the most arresting work in the show is a video installation by Hancock, showing scenes from the fairgrounds of Paris, Texas, juxtaposed with photographs of the lynching of a Black teenager, Henry Smith, which took place on the same site in 1893. Hundreds gather around the makeshift gallows to watch the execution. They seem to be having a very good time.

“Draw Them In, Paint Them Out: Trenton Doyle Hancock Confronts Philip Guston” is on view at The Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Ave., through March 30, 2025.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.