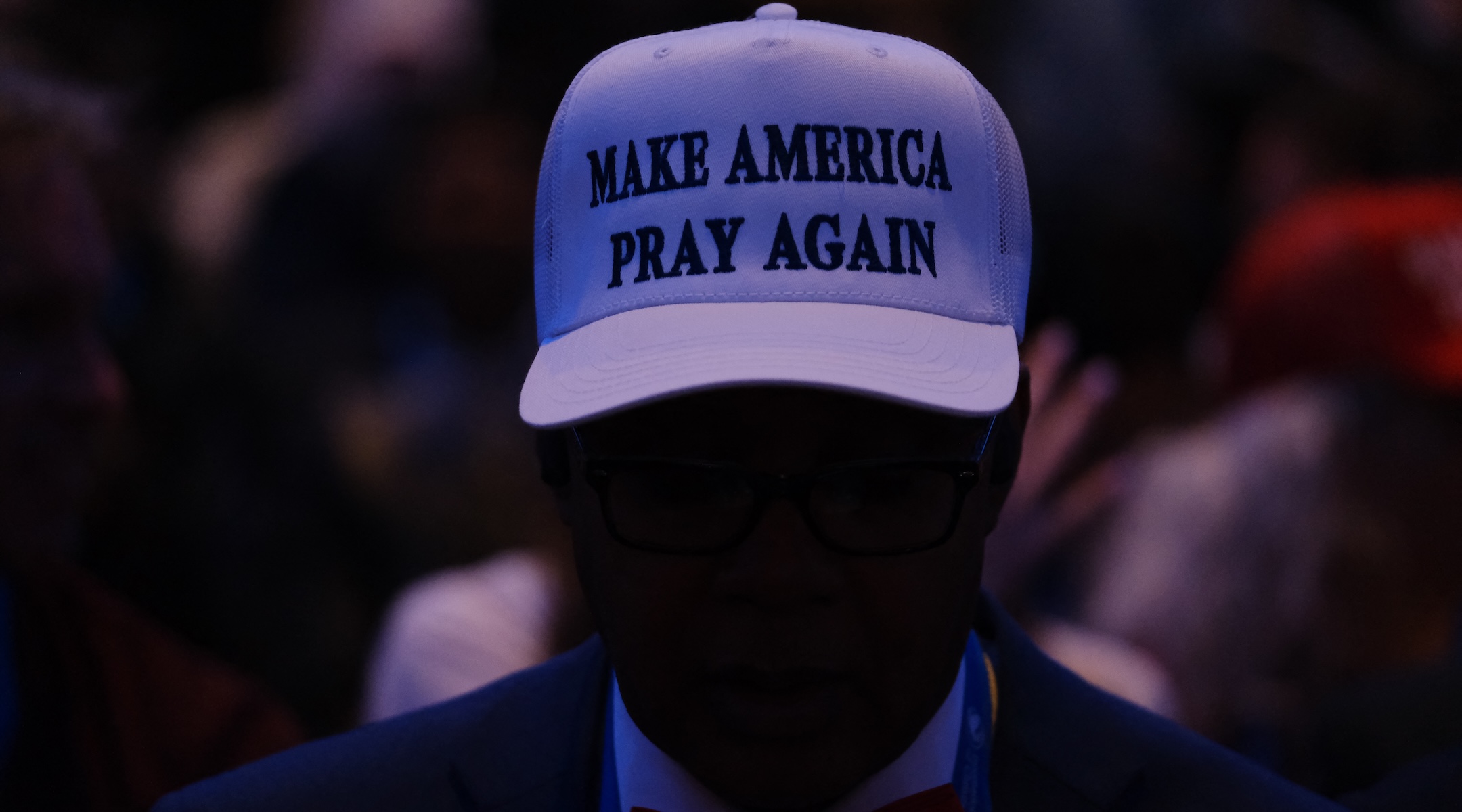

For an energetic subset of supporters, the promise of Donald Trump’s MAGA movement centers on increasing the influence of Christianity in American life and returning the country to what they see as its founding Christian ideals.

Scholars say that through their devotion to Trump, these Christian nationalists have claimed a prominent, mainstream place in Republican politics — a phenomenon that has alarmed Jews and other religious minorities.

And regardless of the result of the presidential election, they aren’t going away, said Julie Ingersoll, a professor of religious studies at the University of North Florida.

“One of the reasons they’ve been successful is they focus on the long-term. To give just a couple of examples: It took them 49 years to overturn Roe v. Wade and they’ve been working on dismantling public education for the same length of time. We can see the impact of that effort all over the country,” she said.

Christian nationalists left their fingerprints all over Project 2025, the controversial proposed 900-page blueprint for a second Trump administration published by the Heritage Foundation and other conservative groups. They also run for office at every level of government, turn out in large numbers for campaign events, and are proving to be a powerful voting bloc in many places. A little more than half of Republicans are “adherents or sympathizers” of Christian nationalism, according to a survey of 22,000 Americans in all 50 states that was carried out last year by the Public Religion Research Institute.

Opposition to the separation of church and state, abortion and LGBTQ rights are among the principles that unify the Christian nationalist movement, but it has no central leadership or theology.

As the movement grows more confident about the prospect of a Christianized America, leaders representing different streams have made some specific proposals. Some want to shutter the Department of Education, seeing it as an obstacle to religious schooling, while others target the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention because they see vaccines as a danger. To crack down on abortion, some suggest using the death penalty as a deterrent. At least one pastor suggested repealing the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote.

In contrast to these concrete plans, Christian nationalists have spoken more vaguely about what would happen to Jews and other religious minorities if they were given the chance to enact their vision for the United States, according to interviews with scholars who track the movement.

“I’m scratching my head to identify any specific policies or even comments that have been proposed from these groups that speak to the status of Jews in a realigned Christian nationalist America,” Matthew Taylor, a scholar at the Institute for Islamic, Christian, & Jewish Studies, said in an interview.

Taylor said the lack of specificity is not an oversight.

“They know that it won’t be popular to describe such an end state as being exclusive and dominated by Christians, so they tend to pitch it in more vague terms about Christianity triumphing or Jesus being glorified and lord over the United States, leaving the rest implied at best,” he said.

The most specific articulation found by Chelsea Ebin, a Drew University professor who studies the Christian right, is one she recently extracted from an influential pastor in an interview. She documented the exchange in a draft of a forthcoming academic paper, which she shared with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Ebin asked Ken Peters, the pastor of Patriot Church ministry, for his position on repealing the 14th Amendment, which was enacted to guarantee citizenship and equal protection under the law to formerly enslaved Americans following the Civil War, and was at the heart of the federal abortion protections guaranteed by Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court decision overturned in 2022. Peters said that ending slavery was the right thing to do but that the amendment had otherwise moved the country away from God. He opposes birthright citizenship and protections for immigrants and LGBTQ people.

Ebin asked him how felt about ending protection from religious discrimination under the 14th Amendment. “I’m cool with that,” Peters said.

For less forthcoming Christian nationalists, parsing their public statements requires an understanding of how they differ in their theological frameworks. The spectrum of possibilities can result in a wide variety of attitudes toward Jews: Some are traditional antisemites, but many proclaim a love for Jews while actively trying to convert them as part of an eschatological prophecy that also undergirds their support for Israel.

Calvinist theology and the Baptist church are the origin point for a strand of Christian nationalism known as reconstructionism. This movement sounds obscure — and it is, said Ingersoll, a scholar of reconstructionism. But the admittedly small number of reconstructionists has been extraordinarily impactful, she said.

“They’ve had a lot of influence shaping our broad evangelicalism because of the fact that they got Christian schools — and then Christian home schools — going, and they shaped what those schools look like,” Ingersoll told JTA.

Reconstructionists envision a society based on biblical law and would support whatever form of government is able to enact it. “If a monarch does that, fine. If a democracy or republic does it, that’s fine, too. Or a dictator — they don’t care about the structure,” Ingersoll said.

Regardless of the structure, Jews and other religious minorities must be marginalized in this vision of America.

“These folks say that pluralism is heresy, and they argue that in a biblical society, people who weren’t Christians could still be there, but they would clearly be second-class citizens,” Ingersoll said.

One of the most prominent pastors in this camp is Joel Webbon, the head of Right Response Ministries and the senior pastor of Covenant Bible Church in Austin, Texas. He promotes hatred as virtuous when aimed at the enemies of God, including other religions.

“I hate Judaism, but I love Jews and wish them a very pleasant conversion to Christianity,” he said in a social media post on X on Saturday.

Webbon’s directness and his explicit attack on Judaism are characteristic of his type of reconstructionist Christian nationalism. There’s another major strand of the movement where such talk is not typical. Scholars refer to it as“charismatic,” meaning that adherents believe in the power of spiritual gifts such as divine healing, miracles, and speaking in tongues.

With their focus on the End Times, these nondenominational Christians are usually not very specific about what the country would be like if they held sway. They tend to talk about politics through biblical analogies, such as the prophecy that Trump will defeat Kamala Harris like the warrior king Jehu vanquished wicked Jezebel in the book of II Kings, and then proceeded to reverse the moral decay in the Kingdom of Israel.

Charismatics are Taylor’s primary subject of scholarship and he says that it’s clear enough they too would prioritize Christianity in the public square and in policy-making, especially around questions of abortion and gender and sexuality. As for their treatment of minorities, he said, it’s a little complicated.

“I would separate out the question of what happens to Jews from what would happen to other religious minorities,” Taylor said. “The way that these folks talk about Muslims is different from the way they talk about Jews. The way they talk about Hindus is different from the way they talk about Jews.”

They are sentimental about Christianity’s origins in Judaism; the fact that Jesus and his apostles were Jews is front of mind for them. There’s even a fondness for Jewish ritual, which is why rallies organized by charismatic groups such as the New Apostolic Reformation tend to feature the blowing of shofars and Christian men wrapped in Jewish prayer shawls. In and near this camp are many people who identify as Messianic Jews, meaning they believe that practicing Judaism and worshiping Jesus are compatible, a belief rejected by all major Jewish denominations.

Jews by the ordinary definition of the term, however, would likely be relegated to a protected second-class citizenship akin to the dhimmi status of Jews under Islamic law, Taylor said.

“There’s a sense of recognition that they are, that Jews are, contiguous with Christian belonging in some way, but that definitely would not give them an equal voice in terms of policy-making or setting the political agenda or having civil rights,” he said.

Muslims, meanwhile, would be treated far worse.

“The charismatic world views Islam as a demonic religion,” he said, referring to the fringe belief that the Muslim faith was inspired by evil demons. “And so I think they would seek to curb, if not eradicate, some Islamic prayer and practices, at least in the public square, if not also destroying it in private.”

There’s a third major category: Christian nationalists who are Catholic. Their handiwork can be found in the work of Project 2025, according to Ingersoll.

“The basic tenor of it and the underlying assumptions, especially the pro-family politics, are drawn from Catholic natural law theology,” she said. Project 2025 is considered perhaps the most mainstream articulation of Christian nationalism. It’s controversial enough that Trump distanced himself even while dozens of his former staffers were involved in drafting its proposals.

There’s less attention paid to Jews and Israel by the Catholics than by the other two groups, which are Protestant, because their theological framework is different and they have different beliefs about the end of the world.

Historically, divisions among the different strands of Christian nationalism have been bitter, but they have made common cause in their support for Trump. Taylor predicted the fissures would reemerge if Trump takes office and the different visions compete for influence.

“They are drawn to Trump for different reasons, but they are all unified in supporting him, which has given at least a veneer of unity to the movement,” Taylor said.

But even if Christian nationalists don’t ultimately agree on exactly what a Christian America would look like, they are working to pull the country in the same direction — one that scholars agree isn’t very hospitable for Jews.

In one vision for the country that has allowed Jews to thrive, what it means to be fully American is ever-expanding. But pluralism isn’t this country’s only political tradition.

“There’s a growing movement that thinks what being American means should be held tightly,” Ingersoll said. “Held tightly by Christians.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.