Last month, clergy from 15 faith communities in Northern Virginia — Jewish, Evangelical, Mainline Protestant and Muslim — gathered at a local park to plant an elm tree. It was an optimistic gesture (they called it “Growing Hope in Democracy”) inspired by the anxiety all of their congregations were feeling about the upcoming election — not just the outcome, but the violence, polarization and discord that has surrounded the entire campaign.

“If God forbid things go sideways after the election, look around at your neighbors,” Rabbi Michael Holzman, of Northern Virginia Hebrew Congregation, recalled saying at the event. “We are going to be the people that hold together our local community.”

A sapling might not strike you as the boldest response to an election that some are calling the most divisive in American history, but Holzman, 50, said that interfaith gatherings like the one in Northern Virginia “create a moral ballast that holds the ship of state upright.”

Holzman is committed to using faith as an antidote to political polarization. At NVHC, a Reform synagogue, he helped create the award-winning Rebuilding Democracy Project to bring Jewish values and texts to bear on creating constructive civic and communal dialogue. A national, nonsectarian version, the American Scripture Project, launched in 2022.

Holzman has also partnered with Rabbi Rachel Schmelkin, the former director of Jewish programs at the One America Movement, an interfaith effort to cool “toxic polarization” and bridge community and political divides. Schmelkin, 36, now an associate rabbi at Washington Hebrew Congregation, created a ritual during the COVID pandemic that inspired this month’s tree planting.

In 2017 Schmelkin was the associate rabbi at Congregation Beth Israel in Charlottesville, Virginia, when neo-Nazi marchers came to town. The experience inspired her work at One America and now at Washington Hebrew, an 1,800-member Reform congregation and fixture among the capital’s political and government class.

I spoke to Holzman and Schmelkin Thursday on Zoom, days before the 2024 election, in the hope that they could provide some encouragement, Jewish wisdom and practical advice for voters who can barely hold it together in the midst of a deadlocked campaign. Does Judaism offer perspective on overcoming political strife? Are houses of worship closing or widening the divides between Americans? And is civil dialogue what anybody needs right now, when the stakes in the election feel so high?

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Rabbi Holzman, I know you’ve been doing this work about democracy and polarization at least since 2016. How are you feeling about the progress that has been made, or the lack thereof, whether in your corner of the world, or more broadly?

Holzman: It’s hard to determine at the moment, because we’re right in the middle of the noise and conflict that is natural around elections. On the positive side, since 2016 there has been a tremendous upswing in the number of organizations that are working to strengthen our civil society. Philanthropy has poured in a ton of cash into this area, including in supporting the work that faith communities are doing, from the more mechanical things like making sure the vote is secure and fair, to the more cultural, values-based things like strengthening norms and teaching people skills of dialogue.

The negative has been that we’ve seen a real rise in political violence. It was bad in 2016 and it’s worse now, and I have really deep fears of political violence, which hopefully people’s better angels will work against in weeks and months to come.

Rabbi Schmelkin, I want to ask about your congregants. What are their fears about the next couple of weeks, and maybe, what are they feeling hopeful about?

Schmelkin: I do think people are concerned about political violence. There’s a lot of fear right now that the wrong candidate will win, whoever they feel is the wrong candidate, and what that will mean for this country and in their personal lives.

I also sense some confusion, and that the Israel-Hamas war has made people second-guess who they should vote for and are surprising themselves.

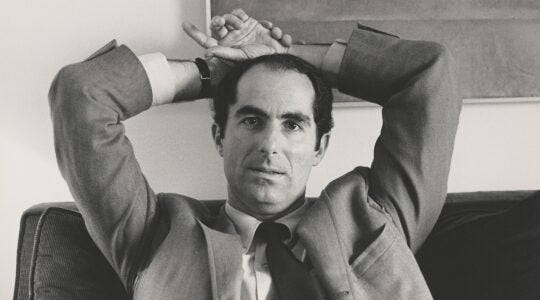

Rabbi Michael Holzman of the Northern Virginia Hebrew Congregation speaks at an interfaith ceremony in Herndon, Virginia, Oct. 20, 2024. Clergy from an array of denominations planted an American Elm tree as part of the “Growing Hope in Democracy” event. (Andy Lacher)

Is the dialogue in your communities civil? How willing are people to debate across political lines?

Holzman: Before Oct. 7, I was operating under the assumption that my community had largely sorted itself, like the rest of American society had sorted itself. In that way, a small minority of people were very quiet conservative and Republicans; almost nobody was a MAGA Republican. Oct. 7 elevated people’s emotions, and in the Jewish community created divisions around support for the State of Israel. I don’t think I have a lot of anti-Zionists in the congregation, but certainly a lot of people who are more willing to criticize the conduct of the war and the number of Palestinian casualties, and other people who felt like the real topic was Palestinian terror and the barbarism of Oct. 7.

I’ve been quite impressed with the way in which people have been able to talk about that openly and disagree with each other within the congregation, largely because we have drummed it into the congregation’s head about the values we have around respect and honesty and courage when we talk with each other. We use the language of covenant, and that membership in the congregation has moral value, not just a financial responsibility.

What does Judaism bring to bear on these notions of democracy and ending polarization?

Schmelkin: Judaism is replete with all kinds of examples of rabbis who disagree with each other. We see this in the Talmud, where the minority opinion is preserved and articulated over and over. There are also these incredible texts that teach us that we should show compassion even to our enemies. So for example, if your enemy’s ox has strayed from their home, or is stuck down under some kind of a heavy load, you’re supposed to return the ox or lift the ox up. And among the many answers to this in the Talmud is that we should prioritize helping our enemy because we likely have feelings of negativity, ill-will, distance, estrangement, etcetera towards them. By helping our enemy, we force ourselves to suppress these feelings and express compassion instead.

That raises for me the question of reciprocity, especially in terms of meaningful conversation across political divides. What happens when one side seeks a conversation in good faith, and the other side says, well, you’re the enemy. How am I supposed to have a civil conversation with someone who doesn’t want to have a civil conversation with me?

Holzman: Well, they’re probably not the person to have the conversation with, from my view. Because you’re right: There does actually have to be an openness from both parties to do this or it won’t work. One of the things that I have learned since Oct. 7 is that sometimes it’s actually not the right time to try to have the conversation. It doesn’t mean not ever, but not now, because we’re too agitated, we’re too emotional, we’re too upset, and we’re actually going to hurt each other more and do more damage.

Right now, when we’re feeling really vulnerable as Jews, it’s natural that we would feel like support for Hamas verbally is harm to us personally here in America, even though I’m not worried that I’m going to be attacked by a terrorist. But, God willing, that will pass, and in months or years to come we can sit down and have an intelligent conversation with someone we disagree with, who holds views that we find to be atrocious, because we’ll be in a stronger place emotionally.

But what happens when the harm isn’t emotional or hypothetical, but real? What if the other side represents a series of values, policies or opinions that really will cause objective harm in the real world, either to a class of people, or the environment, or public health? Do you still have to enter into that conversation in the spirit of, “I respect what you’re saying,” or is it time to take the gloves off?

Schmelkin: I don’t think that you have to choose. I am in dialogue with people who are anti-abortion, even though I am very much in favor of reproductive rights and choice. I’m in those conversations at the same time that I’m showing up to protest Supreme Court decisions on abortion. Those people know that, so I’m making my voice heard while at the same time trying to understand another perspective and share mine with the people who are willing to listen — not to convince them, but to share my own human story behind that issue, and to hear their human story behind that issue.

Holzman: Rachel facilitated a group at my synagogue with an evangelical church, and brought that group to a point where the two sides were ready to talk about abortion together, and it was one of the most spiritually powerful experiences in my entire life. Tears were just flowing as people told their stories and what was meaningful to them and why this issue touched them so deeply. The group felt closer together afterwards, after talking about abortion together. That’s what we’re supposed to do as human beings.

In this election you have one candidate, Kamala Harris, who in her closing arguments has said she will listen to everyone, including “people who disagree with me.” By contrast, Trump has spoken of his opponents as “the enemy within,” and at a North Carolina rally Wednesday afternoon referred to Democrats as “horrible people,” adding, “Some people you just can’t get along with.” Do you have hope in a country where a major party leader appears to reject the very idea that polarization is bad for the country and bad for democracy? Do you worry that for all the great work being done on the ground, you can have leadership that just really undermines all that?

Holzman: Donald Trump is a uniquely talented wannabe authoritarian, and I don’t think there’s much debate about that. But what’s more important is to look at the voters. The man has 50% of the country behind him, and we should be asking why, and we should be trying to understand our fellow citizens and the reasons they’re supporting him. I just saw data that the biggest divide in our country is between non-college-educated white men and college-educated white women. It’s just a gigantic gap on every subject, on every policy topic. How often do college-educated white women interact with non-college-educated white men, and vice versa? How do we get people to interact with each other? How do we get people to hear each other’s stories, to understand what they’re struggling with?

What’s your advice for people come next Wednesday morning, when neighbors are going to be angry at neighbors, no matter who wins — assuming we have a winner. How do you engage as a community in the wake of a bitter campaign?

Schmelkin: I’ll share what I once learned from Rabbi Michael Holzman — that at least at synagogues, we need to do what we do best, which is provide Jewish ritual and prayer and music and spirituality and study. We’re not going to solve it, but what we can do is lean into the things that bind us together. If we’re lighting Shabbat candles on Friday night, it doesn’t matter who voted for which candidate, because we’re lighting Shabbat candles together. If we’re in Torah study and we’re studying the parsha [the weekly portion], it doesn’t matter. It shouldn’t matter who you voted for, because we’re studying Torah. And I think that we’re going to have to elevate that idea and do it more and more.

Rabbi Rachel Schmelkin, left, moderates a debate between Rabbi David Saperstein, a liberal, and former White House official Tevi Troy, a conservative, at Washington Hebrew Congregation in Washington, D.C., Oct. 14, 2024. (Courtesy Washington Hebrew Congregation)

Holzman: Judaism teaches us that we’re supposed to believe in atonement and forgiveness. We’re supposed to believe that the people who disagreed with us in this election are still in community with us, and we have to find ways to heal our disagreements. And so if we’re the ones who are afraid because our side lost, then that is precisely the time to find our neighbors and say, “Hey, we’re afraid. Can we talk about it?” Can we come together and show compassion to each other and heal? And the people who are more confident because their side won should be the ones who are showing compassion and embracing those who are afraid because their side lost, and that’s how democracy survives.

That assumes a lot of good faith on both sides. What in your work as rabbis or advocates for democracy suggest that people are willing to reach out across these divides?

Holzman: Going back to your previous question of what Judaism offers here, most local Jewish communities, especially the Reform Jewish community, often serve as the glue of a network of interfaith clergy and institutions that get together on a regular basis and create a network of civic health all over the country, for decades. You see it after a natural disaster or an act of violence. Suddenly, the police and the county officials are calling the local clergy and saying, “Can you help us?” We are in these relationships with Christian and Muslim clergy partners, and we can create a moral ballast that holds the ship of state upright.

Can either of you give me an example?

Schmelkin: I was in Charlottesville at ground zero of the Unite the Right rally in 2017, and the story of that entire summer leading up to that horrible event was the multifaith community showing up together and standing strong together. There were times when the multifaith community literally stood around the perimeter of my former congregation, because local law enforcement was not showing up the way we needed them to. And after that horrible, horrible shooting at the mosque in New Zealand in 2019 — the Muslim community in Charlottesville was really scared after that and I went with a group of local clergy and local activists and we stood outside the mosque during their morning prayers. And it was really a beautiful, beautiful relationship.

Holzman: There was a murder here, in 2017, and it was a Muslim girl who was killed on the street during Ramadan. And everybody thought it was a hate crime. It turned out to be a hate crime, but not an anti-Muslim hate crime, but an anti-woman hate crime. But we stood together as a faith community and produced a ritual that was peaceful, that brought together young people, that helped hold up our local values, and that could not have happened without the cooperation between all the different institutions that existed for decades. That’s a new thing in Jewish history, that we’re serving that role, and I think that in the months to come, that may be a super necessary role.

Has there been talk in the faith community about worst-case scenarios, and what clergy are prepared to do in case of violence surrounding the aftermath of the election?

Holzman: There are already groups that are training clergy on how to be poll chaplains, who stand outside the polling area to be a calming presence on Election Day. And A More Perfect Union: The Jewish Partnership for Democracy has a whole resource center with scenario planning and thinking about how clergy can participate in efforts to tamp down any kind of unrest or potential violence.

As you mentioned, Rabbi Holzman, more and more Americans have been sorting themselves along political lines, and it’s true for Jewish communities as well: Most Jewish congregations tend to be pretty homogenous socially and politically, with Orthodox synagogues tending to be politically conservative and Reform, Conservative and Reconstructionist synagogues leaning liberal, sometimes very liberal. How do synagogues become comfortable places for people in the political minority? Should they be?

Schmelkin: There are lots and lots of synagogues where people feel like they can’t disagree with whoever the Democratic candidate is, and that they’ll be ostracized. I’ve had people come to me and say, “I don’t tell anybody I’m a Republican, because I’ll have no friends.” That’s terrible. We’re bigger than our political identities. I don’t want to be part of a community where people who are Republican think they have to be in the closet. That’s why I’ve been teaching the classes I’ve been teaching at Washington Hebrew. One class I am doing right now is called “Holding Together: Navigating a Divisive Election.” That’s why our senior rabbi, Susan Shankman, in her Rosh Hashanah morning sermon, said that while in order to be authentic she needed to talk about Israel, she understood that people might disagree with her and her office door would be open to those who wanted to discuss it with her.

Their perspective is valued here, and we want to hear their voice.

Holzman: I had a conversation with one of the authors of “The Great Dechurching: Who’s Leaving, Why Are They Going, and What Will It Take to Bring Them Back?” (2013), about why people say they’re leaving their churches and what it would take for them to rejoin. And the number one thing they said would bring them back was a healthy governance, a healthy community where dialogue and relationship was respected. People are hungry for places where they’re not going to be ostracized because of the people who want to make churches and synagogues and mosques monocultural and mono-political.

This week we are studying Parshat Noach. I don’t want to live in the world that Noah was living in, where everyone was doing each other harm. Why would I seek to contribute to that world? That’s the message I’m trying to preach as much as possible to my congregation through this election and through the inauguration, when there’s going to be prophets of fear and harm rampant in our media ecosystem, and I don’t want my congregation to buy into that culture and create the world that Noah was living in before the flood.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.