Paul Mendes-Flohr was introduced to the writings of the German-Jewish scholar and philosopher Martin Buber when he was 18 and volunteering on a kibbutz in Israel.

“Of course, I didn’t understand a word,” Mendes-Flohr told an interviewer in 2012.

Later, however, at Brandeis University, he had an opportunity to study Buber in a more rigorous fashion under the tutelage of Nahum Glatzer, an Austrian Jewish scholar and one of the founding figures of the Jewish studies department at the Massachusetts university.

“He took an interest in me and my work and introduced me not only to the writings of Buber, but the whole aura of German-Jewish thought — the earnestness, the urgency of modern Jewish thought as it took shape in Germany,” Mendes-Flohr recalled.

Mendes-Flohr not only came to understand Buber but became what a colleague, Brandeis historian Jonathan Sarna, called “the leading Martin Buber scholar of our time and a central figure in Modern Jewish thought and history.”

Mendes-Flohr, who died Thursday at 83, served as editor in chief, along with Bernd Witte, of a 22-volume German edition of Buber’s collected works. Fellow scholar Robert Alter, in a New York Times review, called his 2019 book “Martin Buber: A Life of Faith and Dissent” a “scrupulously researched, perceptive biography of Buber that evinces an authoritative command of all the contexts through which Buber moved.”

Mendes-Flohr’s expertise extended well beyond Buber to include modern Jewish intellectual history, philosophy and religious thought. The 62 books he edited, wrote and co-wrote include studies of the Jewish anarchist Gustav Landauer; “The Jew in the Modern World, “ a standard text written with Jehuda Reinharz; and “Contemporary Jewish Religious Thought: Original Essays on Critical Concepts, Movements and Beliefs,” edited with Arthur A. Cohen.

When “Contemporary Jewish Religious Thought” appeared in 1987, it was hailed as a landmark survey of how Jewish thought had been shaped by modernity, the Holocaust and the creation of the state of Israel.

Mendes-Flohr, whose titles included professor emeritus of Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University and Dorothy Grant Maclear professor emeritus of modern Jewish history and thought at the University of Chicago Divinity School, was also highly regarded as a friend and mentor.

“I count among the great privileges and pleasures of my life the contact that I had with Paul over the past two decades,” Alan Flashman, a psychiatrist and friend of the scholar, wrote in an appreciation in the Times of Israel. Flashman recalled how Mendes-Flohr supported Flashman’s 2013 Modern Hebrew translation of Buber’s best-known work, “I and Thou.”

Rabbi Shmuly Yanklowitz of Valley Beit Midrash, an adult learning center in Scottsdale, Arizona, recalled that Mendes-Flohr was a frequent and popular scholar-in-residence. “His teaching style was as rigorous as it was warmly inviting,” Yanklowitz recalled in a Facebook post. “His fascination with history and great literature of the past was balanced by his dreaming of a peaceful future.”

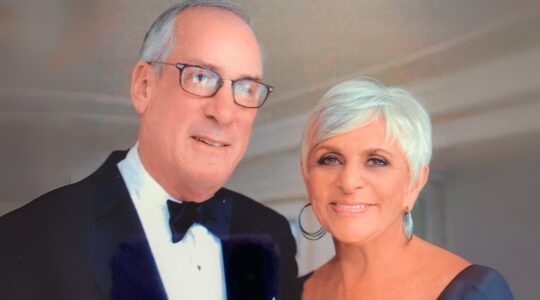

Paul Flohr was born in Brooklyn in 1941. He added his wife’s surname to his own when he and Rita Mendes, a photographer, were married after meeting at Brandeis. The couple moved to Israel in 1970 after he received his Ph.D. from Brandeis. There they raised two children, who, like his wife, survive him.

Mendes-Flohr joined the University of Chicago faculty in 2000, after teaching for 30 years at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

His books include “German Jews: A Dual Identity,” “Progress and its Discontents” (in Hebrew) and “Divided Passions: Jewish Intellectuals and the Experience of Modernity.”

Mendes-Flohr was also the editor of “A Land of Two Peoples: Martin Buber on Jews and Arabs.” Mendes-Flohr took to heart Buber’s notion of “I and Thou,” which describes the basis for genuine dialogue between individuals and between peoples and which Mendes-Flohr sought to apply to the Israeli-Arab conflict.

In a 2022 essay for Sources Journal, “Why Is America Different?”, Mendes-Flohr also remained hopeful for Jewish life in the United States — famously described as the “city on the hill” — despite the country’s growing polarization and intolerance:

Today, at a time when many harbor growing doubts about the promises of America, some historical perspective is in order: in view of the anguished and tragically ill-fated struggle for Jewish emancipation in Europe, American Jews, spared that ordeal, can both avoid complacency and express a healthy mistrust of the city even as they join in a robust song of thanksgiving for their uniquely pluralistic and prosperous home and the unprecedented opportunities it still affords.

Despite his academic accomplishments, what Mendes-Flohr’s students remember most “is his soft voice, warm smile, and earnest effort to personify the dialogical thought he studied,” Samuel Brody, a student and collaborator of Mendes-Flohr, wrote in the Forward.

“The most common word used to describe him, after ‘scholar,’ is mensch,” wrote Brody, associate professor in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Kansas, using the Yiddish term for a kind, decent person. “At office hours, he would ask about his students’ families with such sincerity and persistence that they would sometimes forget what they had come to talk to him about.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.