In 2021, the Orthodox Union declined to put its kosher certification on Impossible Pork, even though similarly vegan “Impossible” foods — its burger, its chicken nuggets — carried the OU seal of approval.

“The Impossible Pork, we didn’t give an ‘OU’ to it, not because it wasn’t kosher per se,” said Rabbi Menachem Genack, the CEO of the Orthodox Union’s kosher division, told JTA at the time. “It may indeed be completely [kosher] in terms of its ingredients: If it’s completely plant-derived, it’s kosher. Just in terms of sensitivities to the consumer … it didn’t get it.”

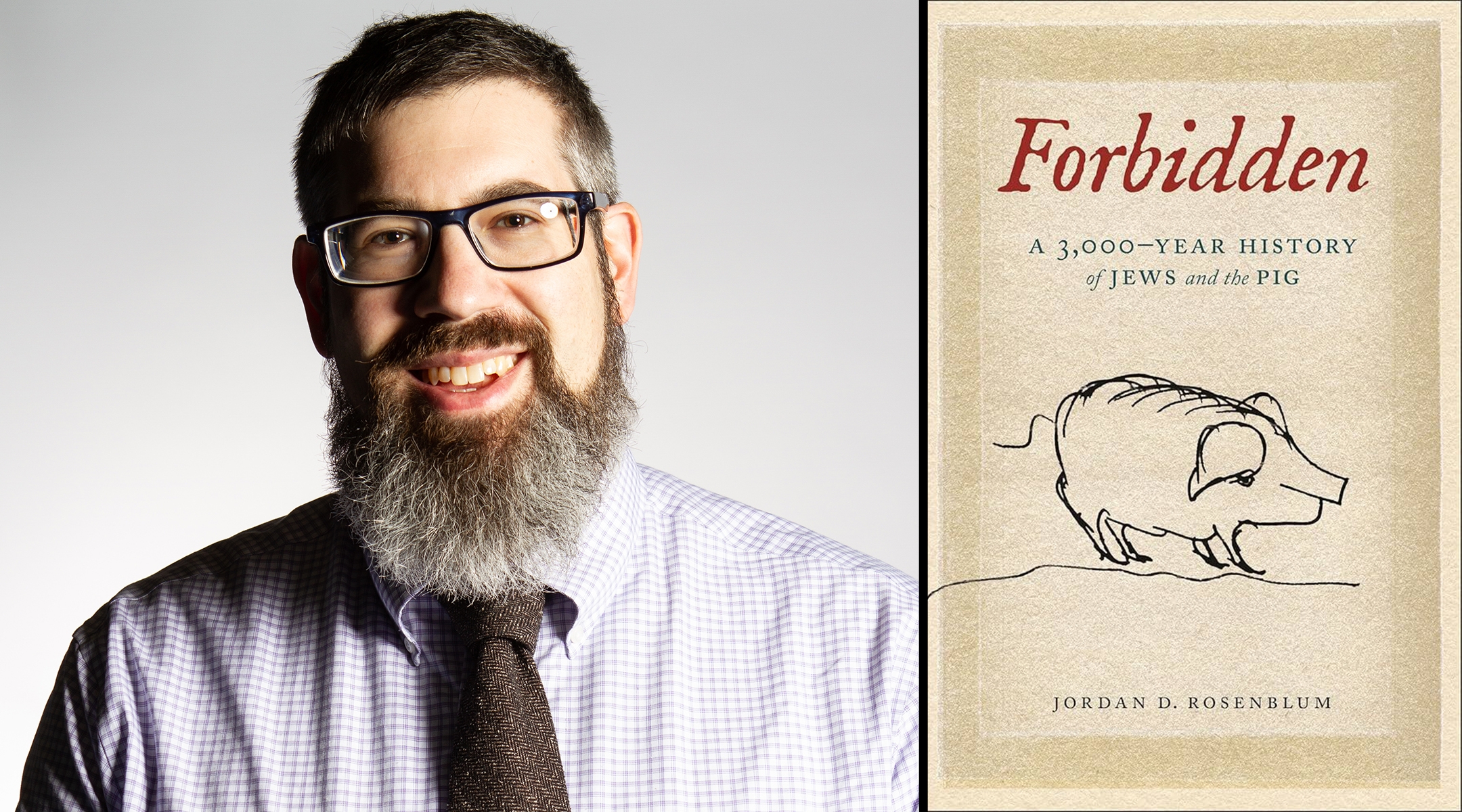

It’s a delicate phrase, “sensitivities to the consumer,” that hints at a long and fraught history explored in Jordan D. Rosenblum’s new book, “Forbidden: A 3,000-Year History of Jews and the Pig.” The “consumer” of course is the Jew, and those “sensitivities” are the result of a history that turned the pig not just into the ne plus ultra of the taboo, or treyf, in Judaism, but, as the symbol of what Jews do and don’t do, an inadvertent marker of Judaism itself.

Rosenblum, a professor of religious studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who has written three other books on Jews and food, has spent 20 years pondering the question, “Why the pig?” After all, in the Torah the pig is no less kosher than other animals Jews were forbidden to eat: shellfish, rabbits, raptors, camels.

“That’s a central part of the argument, that the pig is something so different,” Rosenblum told me. “I love the quote from David Rakoff, the humorist, where he says, ‘Shrimp is treyf, but pork is antisemitic.’ If you go back to the Hebrew Bible, it would make no sense.”

The cover of Jordan D. Rosenblum’s history of the Jews and the pig includes a doodle by Isaac Bashevis Singer. (NYU Press)

The pig’s exceptionalism is undeniable: There are plenty of good jokes about rabbis and ham sandwiches, but hardly any about rabbis and oysters. When formerly Orthodox Jews sit down to write their memoirs, nearly all include the pivotal moment when they first tasted bacon — the ultimate symbol of their exodus. And when the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College celebrated its break with tradition and its first graduating class in 1883 — at the so-called Trefa Banquet — they served clams, crabs, shrimp and frogs, but drew the line at pork.

Rosenblum traces the unique symbolic power of the pig to the Second Temple period, roughly 515 BCE to 70 CE, through the ways that Jews and their Greek and Roman neighbors wrote about Jewish identity. “It was Jews saying that’s weird that you eat it, and Greeks and Romans saying it’s weird that you don’t,” said Rosenblum, pithily summing up a surprisingly vast ancient literature about Jews and pigs whose authors range from the Roman poet Juvenal to the Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo.

In the apocryphal Book of Maccabees, there is the story of Eleazar, a Jewish elder who opts to die rather than eat the pork forced on him by his tormentors — an early version of stories in rabbinic literature in which the pig is not only taboo but the embodiment of the foreign oppressor.

“One of my favorite ones is they say the pig is like Rome, because they’re both deceptive,” said Rosenblum. In an elaborate metaphor, the rabbis note that while pigs have split hooves – a requirement for a kosher mammal – they do not chew their cud, another requirement. Rome, they say, similarly boasts about its courts of law, but they are notoriously corrupt. (Echoes of the metaphor are heard in the Yiddish expression “chazer fissel,” or pig’s foot, referring to people who present themselves as something they are not.)

By the Talmudic period, the pig has become so basted with symbolism that rabbis refer to it only via euphemism – “dvar acher,” or “the other thing” (a weird foreshadowing of the late 20th century marketing of pork as “the other white meat”).

In the millennia to come, Jews and gentiles would deploy the pig in their attacks on each other. The medieval sage Maimonides, writing in Muslim Spain where pigs were also considered unclean, derided Christian Europeans for raising and eating the animals. Christians turned this around on Jews, saying Jews were averse to eating pigs because they reminded them of themselves. Starting in the 13th century, German church and folk art often depicted the Judensau, or Jews’ pig, a grotesque image of Jews suckling from, having sex with and eating the excrement of a sow. The term for a Jewish convert during the Spanish Inquisition, “Marrano,” means “swine,” while conversos were charged with avoiding pork.

“One of the hardest moments of researching this book was when I got to the medieval and early modern chapters, because it’s just antisemitic reference after antisemitic reference,” said Rosenblum. “Take all of the antisemitic stereotypes of Jews as money grubbers and usurers, and stick it into the pig. Throw in some vulgar references. And then it leads to metaphorical and real violence.”

While such anti-Jewish feeling hardly disappeared, the emancipation of Jews in Europe created a new stage in the relationship between Jews and pigs: temptation. Allowed into gentile society or at least its perimeter, Jews were literally served a difficult choice: to eat or not eat the pig.

The last chapters in Rosenblum’s lean but meaty book are a survey of the many ways Jews navigated, and occasionally regurgitated, this dilemma. While some were happy to indulge in the forbidden, others had to decide between transgression and survival, like the Jewish Civil War soldiers whose meager rations were heavy on pork. Rosenblum shares the famous scholarship of Gaye Tuchman and Harry G. Levine, who in 1992 described why American Jewish immigrants fell in love with Chinese food. In “Safe Treyf,” they explain that the pork is almost unidentifiable in one-pan noodle and rice dishes and, what with names like chow mein and moo goo gai pan, who knew what was in them anyway? Chinese cuisine also tended not to mix dairy and meat, avoiding another emblematic kosher prohibition.

And at some point, eating Chinese food itself became an American Jewish tradition, no less than lavish bar mitzvah ceremonies or serving pizza and sushi at an Orthodox simcha.

A Yiddish poster promotes the Soviet pork industry circa 1930. For Jews in the USSR, “Breeding pigs was an effective means to communicate their complete participation in Communism,” writes Rosenblum. (Central Publishing House for the USSR Peoples via Blavatnik Archive)

Rosenblum is as interested in Jewish identity as he is in Jewish gastronomy, and reinforces repeatedly that eating habits are statements of who Jews are, even when the diet is strictly unkosher. Two years after the Trefa Banquet, Reform Judaism produced the “Pittsburgh Platform,” which rejected “all such Mosaic and rabbinic laws as regulate diet,” including the prohibition on pork. But like a militantly secular kibbutz that would serve ham on Yom Kippur, or communist Soviet Jews who promoted pig-breeding, the terms of these various rebellions were still expressed in relation to the rebels’ Jewishness.

Borrowing a term from psychology, Rosenblum calls this “ironic process theory” — what you and I might call “don’t think of elephants.” Or, as Rakoff wrote in his essay “Dark Meat”: “I almost never feel more Jewish than in that moment just before I am about to eat pork.”

“And it’s a wonderful thing,” said Rosenblum, “because the paradox is, how do you show that you’re rejecting your Judaism, but at the very moment, everything you do is pointing back to your Jewish identity?”

As for his own identity, Rosenblum — who earned his Ph.D. at Brown and his bachelor’s degrees at Columbia University and the Jewish Theological Seminary — declined to describe his own relationship, culinary or otherwise, with pork. “Because I found that whatever I say, people will then read everything through the lens of it,” he said. “And my response is, why does it matter? How does that change the story?”

Because, he insists, no matter what they eat, every Jew is in a relationship, metaphorical and historical if not gastronomical, with the pig. Rosenblum sees a through line between Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the 19th-century Reform leader who would not eat pork but kept a pair of pigs named “Kosher” and “Treyf” (to eat his compost) and Rabbi Genack, the OU kosher supervisor who said no to Impossible Pork.

“Probably one of the few things that Isaac Mayer Wise and Menachem Genack can agree on,” he said, “is that there’s just something different about the pig.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.