After Canadian tax authorities revoked the charitable status of the Ne’eman Foundation in August, the organization, which distributes funds to various causes in Israel, began instructing prospective donors to contribute through another recently formed Canadian charity.

Six weeks later, Canadian officials imposed a one-year suspension on that charity, called the Emunim Fund, according to its listing on the Canada Revenue Agency website.

CRA regulators had previously raised concerns about particular Ne’eman Foundation projects in Israel, and a volunteer with Jewish pro-Palestinian group had alleged to the agency that the Ne’eman Foundation was using the Emunim Fund to skirt the revocation.

The agency has not publicly disclosed why it suspended the Emunim Fund, and said in a statement that it is barred by law from commenting on individual cases.

“In cases where we detect a risk of non-compliance posing serious harm to charitable assets or beneficiaries, the CRA will work quickly to address the risk,” said the statement, issued in response to a press inquiry. “The CRA takes any allegations of abuse seriously.”

Still, the swift response by the CRA, the country’s IRS equivalent, surprised Mark Blumberg, an attorney specializing in Canadian charity law.

“I have never seen in my career such swift action from the CRA in dealing with concerns about noncompliance,” Blumberg wrote in a blog post about the suspension, which covers compliance and enforcement issues.

The suspension is the latest in a series of recent CRA actions that have been characterized by pro-Palestinian activists as long overdue, while also putting some Jews in Canada on edge, contributing to a feeling that the country is becoming less hospitable to them, especially a year into Israel’s multi-front war.

The most significant move by the tax agency has been revoking the charitable status of Canada’s Jewish National Fund, which the agency announced in August when it also took away the Ne’eman Foundation’s status.

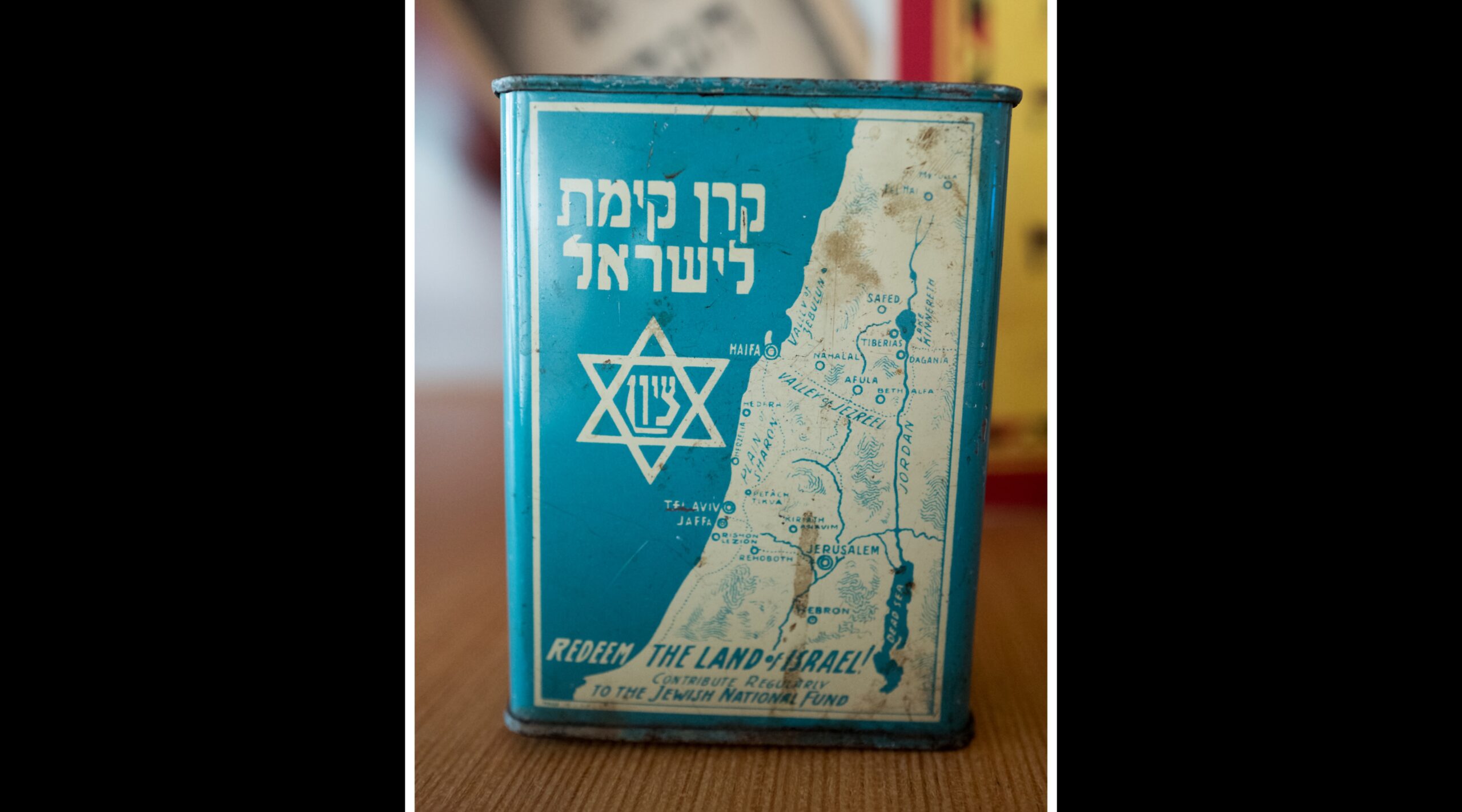

The crackdown has reverberated widely both inside and outside of Canada because the JNF name is linked to the very establishment of the Zionist movement. Many associate JNF with tree-planting in Israel and with once-ubiquitous JNF donation boxes — of the type that even U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris has spoken about nostalgically on the campaign trail this year.

While the Canadian organization is an independent charity, it grew out of and shares a name with Israel’s Jewish National Fund, which was founded in 1901 during the Ottoman era to purchase land for Jewish settlement and exists today as a quasi-governmental body.

Tin with a map of the country of Israel, with text reading “Redeem the Land of Israel, Contribute to the Jewish National Fund”, part of the Jewish Zionist movement, with a Star of David inscribed with Zion, Sept. 20, 2017. (Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images)

“There’s no doubt that the [CRA] revocation fuels the perception that the Jewish community is under assault,” Shimon Koffler Fogel, the CEO for the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “JNF really is the oldest and most widely recognized charity that connects the diaspora community with Israel.”

From the outset of the controversy, JNF Canada framed itself as a victim of antisemitism.

In late July, the group disclosed in a press release that it had been accused by the tax agency of violating the law and warned of an impending withdrawal of its charitable tax exemption.

The press release also said that JNF filed an appeal and was preparing to fight the tax agency in court. Alluding to a multi-year audit of the organization, JNF claimed the tax agency’s “review process was flawed and fundamentally unfair.”

The impropriety stemmed, JNF said in another statement on the same day, from the influence of outside actors who managed to bias government officials against the organization — an apparent reference to a longstanding advocacy campaign against the JNF led by pro-Palestinian groups.

“As a Zionist-inspired organization, JNF Canada has many vociferous antisemitic detractors who we believe have influenced the decision-making process in this matter,” the statement said.

Many activists, themselves stunned at the news of the impending revocation, were only too glad to declare victory and celebrate the tax agency’s move against an organization they have accused of funding Palestinian dispossession.

Corey Balsam, head of Independent Jewish Voices, a pro-Palestinian group, for example, posted on social media that his group had been advocating for government action against JNF for 15 years, with others starting decades earlier.

“We doubted it would ever come to pass, but never gave up and kept on pushing,” he wrote. “JNF is appealing, so we’ll see, but for now this is a big win for justice.”

Many JNF supporters, meanwhile, felt the organization was vindicated in its suspicions when, a few days later, the union representing employees of the tax agency put out a statement connecting the charity to prevailing allegations about Israel’s conduct during the war in Gaza.

“As the union representing over 17,000 CRA professionals, and an organization that will always stand for human rights, we commend CRA’s decision to revoke the Jewish National Fund’s charitable status,” the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada wrote on social media.

“No organization that uses tax-deductible donations to support war or genocidal efforts in an occupied territory should be able to benefit from Canadian charitable status,” it added.

JNF expected to continue operating as usual while mounting its legal challenge, which is why the organization said it was “blindsided” on Aug. 10 when the tax agency finalized the revocation with a published notice. That the date of the notice fell on a Saturday, during Shabbat, only contributed to the JNF’s perception of a “targeted bias.”

The same notice also revealed the tax agency had revoked the status of a second Jewish charity, the Ne’eman Foundation, which came as a surprise because, unlike the JNF, the foundation did not previously disclose that it was in jeopardy. With an affiliated American branch and an office in the Israeli West Bank settlement of Shilo, the Ne’eman Foundation solicits donations on behalf of various Israeli charities serving the settlements and the broader Israeli public.

“CRA seemingly demonstrated that its interest lies in the persecution of Jewish charities that support Israel, not supporting the generous, charitable acts of loyal Canadians,” the foundation said in a statement to eJewish Philanthropy. It did not respond to a Jewish Telegraphic Agency request for comment.

The decisions meant that JNF Canada and Ne’eman were no longer allowed to issue tax-exempt recipients for donations. They were also required to dispose of their assets and stop operating as a charity within a year.

The revocations occurred as many Canadian Jews expressed anxiety amid a reported increase in antisemitic incidents and the Canadian government’s sanctioning of certain Israeli individuals and groups in response to escalating violence in the West Bank. Tension in the community over what the revocations represent is reflected in extensive coverage by The Canadian Jewish News.

Again, talk of what the revocations meant for Canada’s Jews flared up. One conservative columnist, for example, cast the news as evidence against the liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, which “has revealed itself to be no friend of Israel or the Jewish community” since Oct. 7.

“It confirmed rumors that have been flying in the charitable sector that Trudeau’s government was on a campaign to kill off pro-Israel and pro-Jewish charities,” Warren Kinsella wrote in the Toronto Sun.

Fogel, head of the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, however, said that while he believes the tax agency erred, he is hesitant to connect what happened to larger political and social currents.

“I’m not sure that I would assert a direct relationship between the dramatic spike in hatred being directed towards Jews and the CRA decisions,” he told JTA.

A view into the thinking of Canadian tax regulators has emerged from hundreds of pages documenting years of exchanges between the agency and the two charities. These records were released to journalists by the agency after the revocations were finalized.

Blumberg, the charity law expert, who has examined the exchanges, said they contain plenty of evidence of noncompliance by the charities and that he doesn’t find the allegations of bias against the tax agency compelling.

Jewish leaders, he said, are not the only ones who have accused the tax agency of discrimination; Muslim and Christian groups have lodged similar complaints.

“Many secular and religious groups have complained that the CRA is biased against their group when their status is revoked,” Blumberg said in an interview. “A recent extensive study of the CRA by the Canadian Taxpayers’ Ombudsperson on Islamophobia found no bias, and if another study were done on antisemitism, I doubt they would come to a different conclusion.”

In the exchanges, regulators raised objections to particular Israeli projects the groups funded.

These included Ne’eman’s support for programs serving “lone soldiers,” foreigners who join the Israeli military without a familial support structure. Because most lone soldiers are immigrants, this is a popular cause supported by countless other Jewish charities across the Diaspora. Regulators also singled out JNF Canada’s funding of recreational and aesthetic projects on Israeli military bases.

“Increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of Canada’s armed forces is charitable, but supporting the armed forces of another country is not,” regulators wrote to both organizations.

Regulators also objected to activities in areas where the Canadian government doesn’t recognize Israeli sovereignty. For Ne’eman, this included support for Women in Green and the Ir David Foundation, which aim to bolster Jewish presence in areas of East Jerusalem and the West Bank, territories Canada does not consider part of Israel. JNF Canada, regulators noted, supported land reclamation and reforestation projects in the West Bank and Golan Heights, including Canada Park, its flagship project on land formerly belonging to three Palestinian villages.

A donation cannot be considered charitable if it supports activities that are “contrary to Canadian public policy,” regulators wrote to JNF Canada, citing prior court rulings. Support for Israeli military infrastructure has led to JNF Canada being audited in the past, and to the CRA revoking the charitable status of other Jewish organizations.

Charitable organizations supporting the Israeli military and projects located in the West Bank also attract millions of dollars of contributions from American Jews, a reality that has attracted little scrutiny unless the donations are suspected of funding anti-Palestinian extremists.

The significance of these complaints in the revocations remains unclear, as neither particular issue was specifically mentioned in the final notices regulators sent to the charities. The notices contained legal language outlining the alleged violations of Canadian charity law. For both JNF Canada and Ne’eman, authorities accused the groups of failing to properly oversee how funds were distributed in Israel and of using tax-exempt funds to support causes that do not qualify as charitable under Canadian law.

JNF Canada has said it revised its practices in response to feedback from the CRA and that it repeatedly asked for additional guidance to ensure it is in compliance before the eventual revocation. It did not respond to a press inquiry for this story.

Activist groups have continued applying pressure on the CRA. An Independent Jewish Voices volunteer noticed that Ne’eman had changed the “how to donate” page on its website, instructing donors to send contributions to another charity called the Emunim Fund. Incorporated in 2023 under the name Maison Yeshaya 5756, the organization received charitable status in April and changed its name to the Emunim Fund on July 31.

The IJV volunteer took a screenshot of the donation page and filed a complaint with the tax authority on Aug. 12, just after the revocations were made public. On Sept. 26, the CRA issued Emunim a one-year suspension without publicly disclosing the reason. It is unclear whether the complaint triggered the suspension or if officials acted independently.

While suspended, Emunim can continue to operate, but it may not issue tax-exempt receipts and must inform donors of the suspension before accepting a gift.

The longer-term impact of the revocations remains to be seen. On his blog, Blumberg acknowledged that while JNF has major brand recognition, the significance of its case has been overblown.

Using publicly available data, he calculated that Canadian charities sent $362 million Canadian dollars in donations to Israel in 2022, with JNF contributing $4.6 million, or just 1.3%. The Jewish community, with its 950 organizations and $9.2 billion in assets, hardly depends on JNF for its Israel philanthropy, Blumberg wrote.

“There has been a lot of coverage of the JNF Canada revocation and lots of discussions, especially in the Jewish community,” he wrote. “The short answer to the question, ‘How much of an impact will the revocation of JNF Canada have on Canadian Jewish groups doing work in Israel?’ is that there will be almost no impact whatsoever.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.