JERUSALEM — The whoops and applause felt more suited to a rock concert than a prayer service. But this was a gathering of survivors from the deadliest terror attack in Israel’s history, and Asaf Oren had just recited the blessing traditionally said after surviving a life-threatening event.

Oren, whose arm was partially paralyzed by a bullet on Oct. 7, was one of 180 survivors of the massacre at the Nova music festival last year to attend a Shabbat retreat, or Shabbaton, at a Jerusalem hotel organized by Kesher Yehudi, a movement aimed at bridging gaps between haredi Orthodox and secular Israelis and connecting secular Israelis to Jewish heritage. A group of relatives of Israeli hostages also attended.

Two hours earlier, just before candle-lighting marked the onset of Shabbat, the prominent religious leader Rabbanit Yemima Mizrachi delivered a short sermon highlighting the distinction of that Shabbat — the last before the Rosh Hashanah holiday, which would begin a new Jewish year.

“I’m not nervous about Rosh Hashanah this year. Look how many amazing merits we have as a people. When I come to eat the pomegranate, I’ll be thinking of Aner Shapira, who hurled grenade after grenade,” she said, using the Hebrew word—rimon—for both pomegranate and hand grenade.

Shapira, who attended the Nova festival with his friend Hersh Goldberg-Polin, caught seven grenades in his hand in a roadside bomb shelter, hurling them back at Hamas terrorists and saving the lives of 10 people. The eighth grenade exploded and killed him.

After Friday night dinner, Oren and other attendees shared their survival stories, highlighting the role of hashgacha pratit — the concept that God’s presence can be observed in day-to-day life — which, for many, inspired them to commit to increasing their Jewish observance.

Outside of the hotel, the divide between secular and haredi Orthodox Israelis has in some ways never been starker. Surveys show that Israelis are concerned about religious divides in society. The Supreme Court has ordered the army to begin conscripting haredi men who previously received blanket exemptions from Israel’s mandatory draft to study in yeshivas — a longtime arrangement that many Israelis have no longer been willing to make during the longest war in the country’s history. The issue has long festered and has the potential to collapse the government.

And while there are widespread anecdotal reports about secular Israelis drawing closer to religion after Oct. 7, data has not confirmed a broader trend. A survey in December, two months after the attack, found that most Israelis reported no change in their religious outlook. Of those who had drawn closer to Judaism, the majority were haredi or Modern Orthodox already.

But inside the hotel, there was no sign of tension, and Kesher Yehudi was bullish on escalating religious observance among the participants. Although the group has organized four similar Shabbat retreats since Oct. 7, this was the first where attendees were asked to observe Shabbat according to traditional Jewish law — a request made by the organization’s founder and CEO, Tzili Schneider, as a spiritual effort to help bring about the hostages’ return from Gaza.

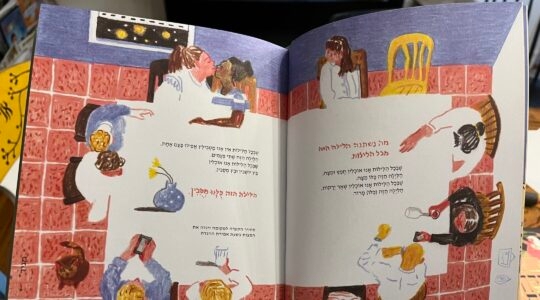

Women light candles at the Shabbat retreat. (Deborah Danan)

In a room adjacent to the one where Oren appeared, a far more somber tone took hold as several dozen family members of the hostages gathered to listen to a lecture by an organizational consultant named Natan Rozen. Offering the caveat that he could never grasp their suffering, Rozen told them they were creating history and could choose to either be consumed by their pain or harness it as the greatest driving force in the world to shape new realities for Israel.

Shelly Shem-Tov, mother of Omer, who was abducted from the Nova party, said Rozen’s words resonated with her.

“I can either take charge and lead others or become a victim,” she said. “This test we’re all going through — as painful as it is — teaches us that we’re all brothers and this Shabbat is proof of that. We must break down these walls — right, left, religious, secular — that we’ve built the past few years. Brothers fight, but they also look out for one another.”

Meirav Berger, mother of Agam, one of five female surveillance soldiers abducted from the Nahal Oz military base, said Rozen’s words struck a chord with her.

Berger, who was there with her husband and younger children, said that since Oct. 7, her family had begun observing Shabbat. The most recent news the Bergers received about Agam came from members of the Goldstein-Almog family, released from Hamas captivity in November, who shared that Agam had been praying frequently and observing Shabbat while in captivity.

“There’s no doubt about the magnitude of our role in this,” she said. Referring to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, whom many Israelis blame for scuttling efforts to secure a hostage release deal, she continued, “It’s just a shame he can’t do what’s right by history.”

Shortly after she made her comments, news trickled in of the assassination of Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah. While some people expressed shock or glee, the news barely registered for Shira Cohen, who, like many participants, was observing Shabbat according to Jewish law for the first time.

“I’m in a total bubble,” she said. “Who cares about Nasrallah?”

A month before Oct. 7, Cohen’s brother was killed in a motorbike accident, plunging her into depression. In a bid to lighten her mood, her best friend, Livnat Levi, convinced her to go to the Nova festival. Cohen resisted, saying she wasn’t a fan of trance music, but Levi insisted. Cohen recalled Levi kissing her at the festival several times on the cheek and repeating, “I love you.” Cohen barely made it out alive, while Levi was killed.

Cohen had decided to keep Shabbat at the retreat in honor of her brother and Levi. The hardest part, she said, was resisting the urge to smoke, so before Shabbat she handed her cigarettes over to one of the organizers to avoid the temptation. Levi’s brother, Eitan, was also at the Shabbaton, though he admitted he was not observing Shabbat, saying that Oct. 7 had jolted his faith in God.

Two days earlier, his family had gathered at his sister’s grave to mark the first anniversary of her death, a difficult day made even more harrowing when a rocket siren yanked him from sleep. Hezbollah had launched a ballistic missile at Tel Aviv for the first time, triggering sirens across central Israel at 6:29 a.m.—the same time rockets had filled the skies on Oct. 7, when the music at Nova abruptly stopped.

Sivan Dabush, too, kept Shabbat for the first time in her life, and like Cohen, refraining from smoking was the toughest part. Dabush is the aunt of Rom Braslavski, who was also kidnapped from the Nova festival where he was working as a security guard. Dabush was originally meant to accompany her sister, Rom’s mother Tami, to the Shabbaton, but Tami pulled out.

“She’s closed herself off to the world,” Dabush said of her sister. “It’s my duty to remain strong for her and the rest of the family. That’s what helped me push through the urge to give up on observing this Shabbat.”

Rabbanit Yemima Mizrachi was one of the leaders at the retreat. (Deborah Danan)

In the hotel lobby, participant Livnat Or shivered from the icy blast of the air conditioning. “They did it on purpose to make sure we dress modestly,” she said, laughing, and referencing another norm of Orthodox life that frequently creates a visible distinction between religious and secular Israelis.

Oren, whose survival story has been dramatized in a play on Oct. 7 currently touring Ivy League universities, stood in the Shabbat elevator with the doors open, waiting for it to begin its automatic ascent. “So I don’t get it, what happens now? God closes the doors?” he quipped.

Having grown up in the haredi Mea Shearim neighborhood of Jerusalem, Schneider said that unlike many of the participants, she had never had the “privilege of devotion” for Shabbat, which she believes allows people to heal from the worst kinds of trauma. In 2012, Schneider founded Kesher Yehudi with a mission to combat mistrust between haredi Jews and other groups, rooted in her belief that the Jewish people are united at the core.

“Certain elements like the media and the government would have you believe we’re divided, but we’ve proved them wrong over and over again,” she said. “The problem is, we’re just not given the opportunities to meet.”

The organization’s activities have grown exponentially since Oct. 7, and in addition to the Shabbaton programs, now includes 14,000 study partners joined in pairings, known in Hebrew as hevrutas, between secular and haredi Israelis. The group also runs learning programs in pre-military academies.

“People are asking what it means to be Jewish. They understand now that it doesn’t matter what your background is, the Sinwars and the Nasrallahs don’t differentiate between us,” she said, referring to the Hamas chief in Gaza. “They hate us because we’re Jewish.”

For Meirav Berger, Nasrallah’s assassination encapsulated the essence of her Shabbat experience.

“He’s dead. You could say, that’s the whole Shabbat,” she said. “Who ever thought we would manage that? It’s God, revealing himself. Now he will reveal himself more and more. From here, the only way is up.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.