This article is part of a series examining how Oct. 7 and its aftermath have changed the Jewish world. You can see the complete project here.

Wars and crises shape language, in both profound and mundane ways. World War II gave us terms like radar, spam — and genocide. Military euphemisms like “collateral damage” (the first Gulf War) and “friendly fire” (the Vietnam War) become part of everyday speech.

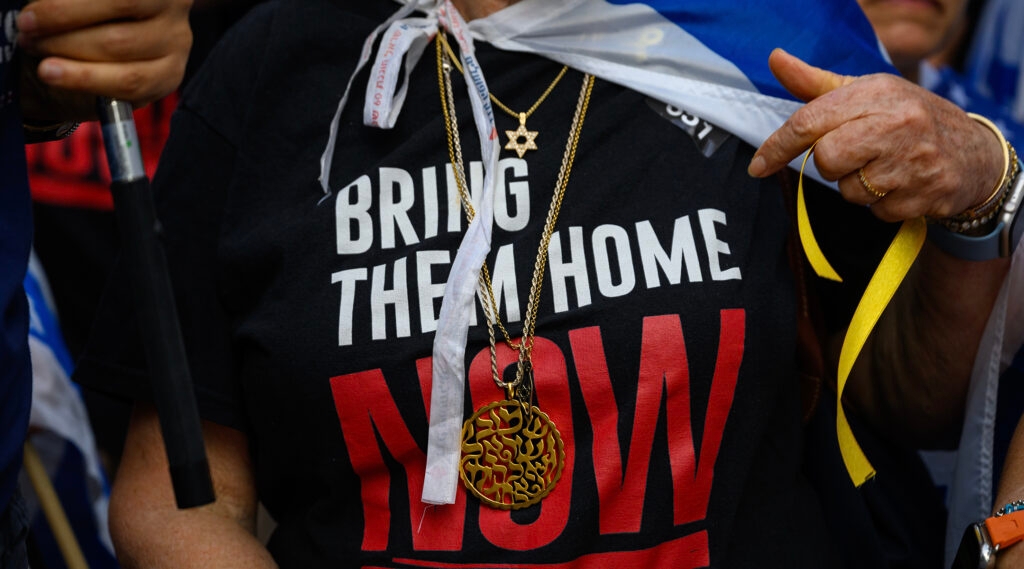

The Hamas attack on Israel and the subsequent war in Gaza and now Lebanon have left their own linguistic legacy, starting with the date of the attacks — Oct. 7 — which, like 9/11, has become a shorthand for the horrors of the day and the trauma and combat that followed. In the United States, pro-Israel demonstrators carry signs reading “Bring them home,” referring to the hostages held by Hamas, while Israelis clamoring for a ceasefire chant “Bring them home now,” adding the adverb to express their impatience.

On the anti-Zionist left, the academic framing “settler colonialism” gained wide currency to describe and deride Zionism, while “Zionism” itself became a dirty word in the protest “encampments” that sprang up on college campuses.

American Jews became familiar with Hebrew words they might never have known before: “mamad” (safe room), “miluim” (army reserve duty), “chayalim” (soldiers), “hatufim” (hostages).

In Israel, the right began applying the term “uninvolved” (bilti me’uravim) ironically to Palestinian civilians, part of the blanket accusation that there are no “uninvolved” — that is, innocent — victims in Gaza. Israeli critics of the government, meanwhile, embraced a lyric from an old Hebrew rock song — “Where is the state?” (“Eifo hamedina?”) — to describe the Israeli military’s failures to prevent the Oct. 7 attacks and the government’s faltering efforts to provide social services in their aftermath.

Demonstrators clamoring for a ceasefire have added the adverb, “now,” to “Bring them home.” (Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images)

The Israeli scholars Michal Kravel-Tovi, Omri Grinberg and Tamar Katriel call these wartime neologisms “tongue prints” — the verbal traces left behind, like fingerprints, after upheaval. In “Speaking After October 7,” a forthcoming Hebrew-language anthology, they enlisted linguists, anthropologists, historians and other scholars to write short essays on an “evolving lexicon of new and repurposed words and phrases” that have gained traction in Israel since the war.

Ahead of assembling our own glossary of such words and phrases related to the war, in English and Hebrew, we spoke to Kravel-Tovi, associate professor of sociocultural anthropology at Tel Aviv University, and Grinberg, an anthropologist and postdoctoral fellow at the Martin Buber Society of Fellows.

Ironically or not, they told us, one of the most common Hebrew phrases to come out of Oct. 7 and the war is “ein milim” — that is, there are “no words” to describe the horrors of the day or how people are feeling since. Days after Oct. 7, Kravel-Tovi, who was on sabbatical in Berlin, was asked by an organizer to speak to colleagues about the attacks. “I didn’t have a voice, and I found myself telling her I have no words. I don’t know how to talk with anyone,” she recalled. Back home, other Israelis were similarly unable to articulate, ending conversations and emails with the phrase.

“I think there is a certain level of resistance to talk,” she continued. “Because if we talk, we indulge in an illusion of order. Language usually orders reality. It comforts us. It gives us some clarity of mind. And with the fogginess and messiness [that came after Oct. 7], I think there is a level of resistance.”

And yet, people must find a way to describe even a foggy reality. Everyday conversations are shaped by the crisis, and a simple phrase like “how are you” — whether asked at a North American synagogue or in an email between Israeli friends — is loaded. Kravel-Tovi and Grinberg say that Israelis are saying goodbye and signing off emails with the phrase “in hope of better days.” Even young secular Israeli Jews have begun saying “besorot tovot” — “may we hear only good news” — a phrase long associated with the Orthodox community.

“We noticed that there are all these different ways of marking what we know is not a regular time,” said Grinberg. “What do you say to each other when you know things just get worse and worse?”

Below is a glossary of some of the words and phrases that have gained currency since Oct. 7.

One of the most common Hebrew phrases to come out of Oct. 7 and the war is “ein milim” — that there are “no words” to describe it all. (Leon Neal/Getty Images)

Bring them home: The phrase became a mantra of the movement to free the hostages, although it took on different meanings to Jews in the United States and Israel. In America, it was a reminder of the fate of the missing, like hostage “dog tags” — gestures of solidarity without any specific political ask; in Israel it is a highly politicized phrase often used to urge the government to strike a deal and negotiate a ceasefire.

Encampment: One of the first references to a campus pro-Palestinian “encampment” came on Oct. 28, 2023, when The Dartmouth newspaper reported on the arrests of students on the front lawn of the Ivy League university’s Parkhurst Hall. By the following May, after a full academic year, the trade publication Campus Safety reported that more than 100 colleges in 45 states had encampments or ongoing protests. In April and May, there were over 3,000 arrests nationwide linked to campus demonstrations of the war, after colleges cracked down on the tent cities.

The encampment as a means of protest owes something to the Occupy movement starting in 2011 (the same year that Israelis protesting high prices set up a tent city in Tel Aviv). “A physical encampment is an activist tactic that escalates activism beyond ephemeral protests like rallies,” according to a sympathetic article about the campus protests in Lookout, a news site in Santa Cruz, California. Critics of the encampments say they make Jewish students feel unsafe, disrupt the campus and discourage constructive dialogue — “a home for a separationist community whose valor was proved by its refusal of entry to persons whose clothing or other outward signs rendered them alien to the communion,” wrote David Bromwich, a professor of English at Yale.

Since Oct. 7, the phrase, “From the river to the sea,” has become ubiquitous at pro-Palestinian protests. (Justin Tallis/AFP via Getty Images)

From the river to the sea: The slogan, in wide circulation before Oct. 7 and included in Hamas’s 2017 charter, generally appears as the first half of the chant “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” — referring to the area between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, which encompasses Israel, the West Bank and Gaza. Since Oct. 7, the phrase has become ubiquitous at pro-Palestinian protests, leading to complaints by Jewish groups that its intent is genocidal. Defenders of the slogan, including Rep. Rashida Tlaib of Michigan, say that freedom for the Palestinians does not preclude an arrangement that allows Jews and Palestinians to both live in historic Palestine. Earlier this month, Meta, the social media giant, determined that the phrase is not necessarily antisemitic.

Moral clarity: Defenders of Israel often use the term to suggest that its critics are hypocritical in not recognizing the uncomplicated villainy of Hamas’s attacks on Oct. 7 or the West’s interests in defending democratic Israel against extremist neighbors who include Iran and its proxies, Hamas and Hezbollah. “In the four months since Hamas’ inhumane Oct. 7 attack on Israel, I have developed more — not less — moral clarity,” New York City Rabbi Elliott Cosgrove wrote in the Forward in February. Rep. Elise Stefanik, the upstate New York Republican, decried “Harvard’s unacceptable lack of moral clarity” on the day she grilled the university’s president, Claudine Gay, over its handling of anti-Israel student protests. After that hearing, Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff also criticized Gay and another university president, saying their “lack of moral clarity is simply unacceptable.” Attorney Alan Dershowitz helped popularize the phrase in the Israel context with his 2009 book, “The Case for Moral Clarity: Israel, Hamas and Gaza,” written a few years after the conservative author William Bennett published the best-selling “Why We Fight: Moral Clarity and the War on Terrorism.”

In May 2024 the trade publication Campus Safety reported that more than 100 colleges in 45 states — including UCLA, above — had encampments or ongoing protests. (Keith Birmingham/MediaNews Group/Pasadena Star-News via Getty Images)

Settler colonialism: An academic historical theory, popularized over the past two decades, settler colonialism understands powerful countries through their mistreatment and displacement of indigenous populations. Over the past year the term became a catchphrase at pro-Palestinian street protests and was deployed at times to justify calls for the elimination of Israel. Activists who apply the model to Israel say the political Zionism of the late 19th and early 20th century was inspired and abetted by European colonial powers, and that Jewish immigration to and the “conquest” of Palestine represented the domination of the land’s indigenous population by white, European Jews. “The plight of European Jewry had some of its roots in colonial conquest,” and “many of those practices have been reproduced in the settler colonial machinations of the State of Israel,” the left-wing magazine Jewish Currents editorialized in August.

Adam Kirsch, author of the 2024 book “On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice,” counters that Zionism was not the project of any great power, while less than half of the Jewish population of Israel has roots in Europe. “The Zionist movement never saw itself as white Europeans colonizing someone else’s land,” he told JTA. “It was a return to the Jewish homeland by Jews who had been in exile for hundreds of years, thousands of years.”

Slicha: The word, meaning “I’m sorry,” can convey a range of meanings — from a casual “excuse me” to a profound request for forgiveness. In the days after six hostages, including Israeli-American Hersh Goldberg-Polin, were reported murdered in Gaza, the word began appearing on placards at rallies in Israel and the United States. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu used it in an address to hostage families. Kravel-Tovi said the impulse to apologize may be a simple expression of condolence, an expression of survivor’s guilt by Israelis, or a lament that they or the government didn’t do more to bring the hostages home.

In the days after six hostages, including Israeli-American Hersh Goldberg-Polin, were reported murdered in Gaza, the word “Slicha” (“I’m sorry”) began appearing on placards at rallies in Israel (above) and the United States. (Chaim Goldberg/Flash90)

Swords of Iron War (Milchemet Charavot Barzel): The government named the operation in Gaza “Swords of Iron,” in keeping with a tradition of naming previous wars in Gaza and Lebanon. Netanyahu was reportedly unhappy with the name, preferring, among other choices, the “Simchat Torah War” for the day on which Hamas attacked. “Swords of Iron” has not become part of everyday conversation in Israel, although it is used by some Israeli media and in official communiques by the Israeli government.

The day after (hayom she’acharei): Used mostly in Israel, it refers to the uncertain future when the war ends — and often frustration with a government that hasn’t shared a detailed plan for what happens when it’s over. “The ‘day after Hamas’ will only be achieved with Palestinian entities taking control of Gaza, accompanied by international actors, establishing a governing alternative to Hamas’ rule,” Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant said in May. “Unfortunately, the plan was not brought for discussion, and worse, an alternative discussion was not raised in its place.” It has also been used in foreign policy and diplomatic circles. “In the absence of a plan for the day after, there won’t be a day after,” U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken told reporters on May 29.

Together we will win (yachad nenatzeach): Before Oct. 7, “Together we will win,” the lyric of a pop song, was a slogan of solidarity chanted by Israelis protesting the Netanyahu government’s plans to strip power from the state judiciary. An article in “Speaking After October 7” describes how after Oct. 7, government officials began using the phrase as a rallying cry — one embraced by some Israelis as patriotic, and ridiculed by others as an appropriation of a slogan associated with the opposition. Today, visitors to Israel are as much or more likely to see “yachad nenatzeach” signage in right-wing areas than any variation on “Bring Them Home.”

Originally a slogan of solidarity chanted by Israelis protesting the Netanyahu government, government officials began using the phrase “beyachad nenatzeach” (“together we will win”) as a rallying cry — one embraced by some Israelis as patriotic, and ridiculed by others as an appropriation of a slogan associated with the opposition. (Miriam Alster/Flash90)

Total victory (nitzachon muchlat): In a speech to Congress on July 24, Netanyahu pledged to achieve “total victory” against Hamas, a phrase he has used in Israel since the start of the war. The phrase is polarizing in Israel. For some, it means the goal of destroying the terrorist group once and for all and ending the possibility of another Oct. 7. For others, it suggests that the government is prioritizing military victory over Hamas at the expense of rescuing the hostages.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.