This article is part of a series examining how Oct. 7 and its aftermath have changed the Jewish world. You can see the complete project here.

“How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?” (Psalm 137)

That, according to Psalms, was the lament of the Jews exiled from their homes in Israel to the land of Babylon, where a harsh new reality made the old prayers and songs seem irrelevant.

It has become a mantra that “everything changed” for Jews and their allies after the deadly attacks of Oct. 7. Grief and anger shattered their beliefs and certainties. Some prayers felt impossible to say; others took on new meanings.

How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? We asked a number of writers, thinkers, rabbis and everyday folk to consider a Jewish text that they held dear and how its meaning changed for them since Oct. 7 and the war that followed. Is there a prayer — or a proverb, a song lyric, a quotation, a poem or piece of prose — that became harder to say or more difficult to believe? Is there a verse that has become particularly resonant, or a phrase that has taken on new important meanings?

Their answers appear below, showing the evolution of Jewish thought in a year that literally and figuratively defied belief.

Psalm 121: “The guardian of Israel neither sleeps nor slumbers”

Dr. Erica Brown is the vice provost for Values and Leadership at Yeshiva University and the director of its Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks-Herenstein Center for Values and Leadership. Her forthcoming book is “Morning Has Broken: Faith After October 7th” (Koren).

Prayer, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik once wrote, helps us articulate “thoughts and emotions, deliberations and troubles” that surge through the depths of our souls where “hopes and aspirations” live in close proximity to “despair and bitterness.” For these past 12 months, Psalm 121 and its continuous recitation in community has been the text of my soul. One verse of it permits me to rest: “See, the guardian of Israel neither sleeps nor slumbers” (121:4).

Since Oct. 8, I have gone to bed with the dread of knowing that in the morning terrible news is likely waiting for me, afraid that the morning will bring fresh violence, more retaliation, another photo of a soldier, a beautiful smiling face of one already dead. The time difference is a distancing mechanism that keeps Diaspora Jews slightly out of step with Israel. In three places, the sages of the Talmud ask, “Does God sleep?” (See here, here and here.) Stay awake, we beg God, “when the Jewish people are in a state of suffering.”

I am comforted by words of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks: Prayer “gives sacred space to the tears that otherwise would have nowhere to go.” Across the abyss, I reach out to God — the guardian of Israel who neither sleeps nor slumbers — for our protection. These are my very last words that put the distractions of the day to bed as I prepare for the darkness of night’s uncertainty.

Unetaneh Tokef: “Who shall live and who shall die”

Letty Cottin Pogrebin is an author, activist and founding editor of Ms. Magazine. She is the author of 12 books, most recently “Shanda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy.”

The third paragraph of the Unetaneh Tokef, recited on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, has never failed to stir within me a roiling tide of awe and reverence, fear and hope. But last year, when I stood before the open ark and heard those quake-worthy words, they aroused only dread and tears. Bert, my husband and soulmate was sick, his strength waning, the brilliance of his mind fading along with his sight, voice and hearing. So, for the first time in our profoundly blessed 60-year marriage, I went to shul alone and “who shall live, who shall die” was no longer hypothetical. I knew the answer. No amount of “repentance, prayer, and righteousness” could “avert the severity of the decree.” The only remaining question was would he “have rest…be at peace” and be “serene?” I prayed for the strength to help him achieve all of that. When my silent weeping escalated to heaving sobs, I left the sanctuary.

Then came Oct. 7, a shock unimaginable just days before when we’d collectively intoned “who shall live, who shall die.” Five months later, Bert passed away, compounding the pain of my peoplehood grief with the most momentous personal loss of my lifetime. Today, the world is a different, emptier, more menacing place. I’m pretty sure that when I hear the Unetaneh Tokef, the weight of all these bereavements will once again send me out of the sanctuary weeping.

“Hatikvah,” Israel’s national anthem

Idit Klein is the CEO of Keshet and is an Israeli-American living in Boston with her family.

A friend once said to me, “You look at a glass with a single drop of water in it, and immediately imagine the glass as full.” Hope has always been my inner compass. As the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, I grew up with a sense that anything was possible because they had survived the impossible — survived, and even more astoundingly, rebuilt lives of love and joy. So Israel’s national anthem, “Hatikvah,” The Hope, always felt like a personal anthem, too.

Early one morning a few days after Oct. 7, I moved between sleep and wakefulness thinking and dreaming about the hostages. Suddenly, I woke up when I heard myself singing, “Od lo avda tikvateinu,” “We have not yet lost our hope.” Immediately, I cried and then laughed; and cried and laughed some more. Since then, those words have echoed and reverberated within me. In moments of sorrow, anguish, uncertainty and fear, “Od lo avda tikvateinu” are the words I return to over and over. These words have anchored and buoyed me. They remind me of our people’s long history of survival and resilience, and that choosing hope is the only way forward. I am bound to hope and every day, I am grateful for the words that remind me that hope is bound to me.

(Sarayut Thaneerat/Getty Images)

Job 14:7: “There is hope for a tree”

Rabbi Shai Held is president and dean at the Hadar Institute and author, most recently, of “Judaism is About Love.”

The world seems so dark and so hopeless so much of the time. To buoy myself lately, I have been reflecting on the Hebrew word for hope, tikvah, which also means “thread,” as in the phrase tikvat hut ha-shani, the cord of crimson thread that Rahab hangs outside of her window as a sign for Joshua and the Israelites to let her family live (Joshua 2:18). I find myself thinking: Sometimes hope is little more than a very slender thread, but that thread is everything, almost literally separating life from death.

A verse in Job reflects on the hope suggested by a tree:

There is hope (tikvah) for a tree;

If it is cut down it will renew itself;

Its shoots will not cease.

A chopped-down tree may look dead but under the surface there is the possibility of more life. Perhaps this is our task: to affirm (to insist) that even if much of what we most value and treasure is cut down, growth and change, and renewal can (will?) yet come.

I am not optimistic, but I am hopeful — at least some of the time. We should not confuse hope with optimism. If anything, the literary critic Terry Eagleton writes, “hope and temperamental optimism are at daggers drawn.” The point Eagleton is making is profound and essential. Optimism, he says, is “a form of psychological disavowal… a moral evasion”; it “does not take despair seriously enough.” Perhaps counterintuitively, optimism is thus “the enemy of hope, which is necessary precisely because one is able to confess how grave a situation is.” So what is hope? It is, in the philosopher Paul Ricoeur’s wonderful phrase, “a passion for the possible”; it is, Eagleton explains, “a movement toward the good, not simply a craving for it.”

In other words, hope involves commitment. (Wanting things to change without committing to help making them change is wishing, not hoping.) So as we enter these days of reflection, let us examine both our lives and the world in which we live them, and let us grasp for hope, however slender and vulnerable it may be.

Birkat Shalom: “Grant us peace”

Rabbi Joshua M. Davidson is the Peter and Mary Kalikow Senior Rabbinic Chair at Congregation Emanu-El of the City of New York.

“Grant us peace, Thy most precious gift, O Thou eternal source of peace, and enable Israel to be its messenger unto the peoples of the earth.” The Union Prayer Book’s 19th-century rendering of Birkat Shalom, though now modernized, is still recited in Reform synagogues across America. For many Jews, this bracha, or blessing, in any language expresses their highest ideal: peace.

And yet the words stuck in my throat for much of the past year. For months after Oct. 7, I would recite them aloud, while saying to myself, “No, not yet.” Peace won’t come until Israel is safe, and Israel isn’t safe while Hamas still threatens it. “War now, peace later,” I thought at the time.

Who ever heard of a rabbi who couldn’t pray for peace? It’s how I felt.

But now it’s later. Hamas may still threaten Israel. Hezbollah surely does. And Iran too. But with 100 hostages still to return home, most, please God, to the arms of their families, others sadly to the soil of the land — with all the heartache and loss on both sides of the fight — now I pray desperately that Israel can be that “messenger” of peace, or dispatch its messengers to end this war. There must be peace in the land and between the lands. For Israel’s sake.

“Praised be Thou, O Lord, Giver of peace.”

Pirkei Avot 1:14: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? If I am only for myself, who am I? And if not now, when?”

Rabbi Dr. Haviva Ner-David is rabbinic founder of Shmaya: A Mikveh for Mind, Body, and Soul, on Kibbutz Hannaton. She is the author of “Dreaming Against the Current: A Rabbi’s Soul Journey” and the novels “Hope Valley” and “To Die in Secret.”

I am a rabbi, author and peace activist. Living in Israel, where Jews are in power, my activism — although based on partnership among Palestinian and Jewish Israelis and the holding of both narratives as equally true but only half-true — emphasized Palestinian suffering and oppression.

Then Oct. 7 happened.

Seeing the brutality of Hamas and the support they received, shifted something inside me. For years, it had been my custom to stand for “Hatikvah” without singing the words, which alienate Palestinian Israelis who also have a deep connection to this land. But when I went to Hostages Square right after Oct. 7, I sang along, weeping, affirming for myself Jews, too, have a right to live in security on this land. “If I am not for myself, who will be for me?”

At first, I supported the war in Gaza. Israel has a right to defend itself. But when I saw the extreme suffering in Gaza, realized the hostages’ release is not a top priority of this war, and understood that a Palestinian state alongside a Jewish one is not Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s endgame, I started demonstrating for a hostage-ceasefire agreement. I told myself: “If I am only for myself, who am I?”

And so, I have revved up my activism over the past year. This is not how I want my reality to be, but it is the reality I am living in. When my grandchildren ask me where I was this year, I will tell them: on the streets fighting for peace, security and freedom for all. The urgency of the moment calls for action. “If not now, when?”

Tikkun Olam

Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie is the co-founding spiritual leader of the Lab/Shul community in NYC and the creator of the ritual theater company Storahtelling, Inc.

The hopeful, well-worn slogan “Tikkun Olam” feels different these difficult days, one year after the horrors of Oct. 7, as the violence and uncertainties persist. I vaguely knew that the origin of this phrase, often used to express Judaism’s hope in fixing the world, was linked to the moral dilemmas of freeing captives. But I didn’t fully grasp that our people have faced such heartbreaking challenges throughout history. I didn’t grasp that the original meaning of this call for repair was rooted in rupture.

During Roman times, the Talmudic sages sought to balance communal obligation to redeem every sacred soul held captive with the public responsibility — mipnei tikkun ha-olam — to avoid escalating ransom demands. Tikkun Olam originally referred to maintaining the system as a whole — tragically, sometimes at the cost of individual lives. Yet the law remains unresolved, recognizing that when loved ones are at stake, rules can bend.

Today, we confront this terrible reality, on a scale of sorrow and strife that strains the fabric of Israeli society and Jewish communities worldwide. How do we bring them home? How can we repair this rupture and co-create a better world?

Our sages taught us to navigate the tensions between law and love, firm policies and flexible compromises, to honor every life and the diversity of opinions. However we emerge from this tragic chapter, it must be done through respectful dialogue despite deep differences, as our tradition models. We must ensure the endurance of our community and humanity. We must reclaim, repair and reimagine what it really means to rebuild, together, a much safer, kinder and more hopeful world.

Parashat Shoftim: “Our hands did not shed this blood”

Ilana Kurshan is the author of “If All the Seas Were Ink” and “Children of the Book,” forthcoming from St. Martin’s Press.

The week that Jerusalem buried the Israeli-American hostage Hersh Goldberg-Polin included the Shabbat when we read Parashat Shoftim (Deuteronomy 16:18-21:9), which focuses on leadership and justice. The final verses of this Torah portion teach about eglah arufah, a ceremony that is performed when someone is killed in the middle of nowhere. When the dead body is found, the community leaders measure to find the closest town. The elders of that town take a calf that had never been worked and bring it down to the river, where they chop off its head. They then wash their hands over the calf and say, “Our hands did not shed this blood, nor did our eyes see it done,” and ask forgiveness from God.

Hersh’s parents were members of our shul — my husband had met with Hersh’s father Jon to roll the Torah back to the beginning on the night before that fateful Simchat Torah when Hamas attacked. “If only we could roll back time to that moment before everything changed,” my husband has often lamented. But it was not to be. Hersh’s body was found and all the members of our community streamed down like a river, lining the streets leading from the Goldberg-Polin family home to the cemetery, holding Israeli flags and weeping and singing through our tears. Many of the balconies of the houses in our neighborhood are draped with large black-and-red posters reading “Bring Hersh Home,” and in the wake of his death, these posters have been scribbled with the word slicha, “I’m sorry.” Because who among us can truly say that our hands did not shed this blood? Who among us can say that our elders and leaders did not see it done? In this season of Elul, what can we do but ask for forgiveness?

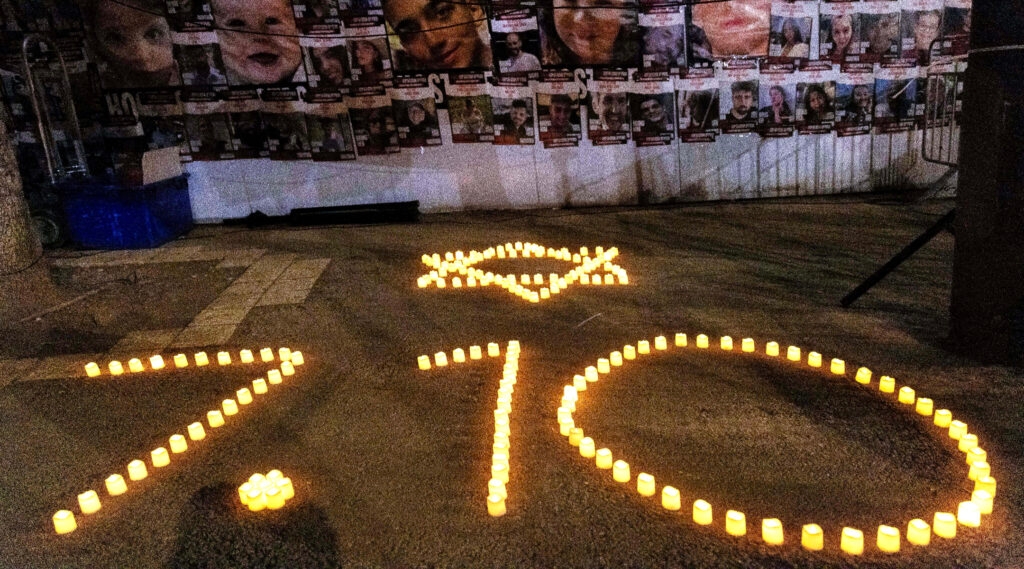

Candles arranged in the shape of the date “Oct. 7” and a Star of David at a vigil in Jerualem, Nov. 7, 2023. (Ahmad Gharabli/AFP via Getty Images)

Birkat HaChodesh: The blessing of the new moon

Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander is president and Rosh HaYeshiva of Ohr Torah Stone, a network of 32 Orthodox educational institutions and leadership development initiatives in Israel

The routine prayer of Birkat HaChodesh, recited on the Shabbat preceding each new Jewish month, has taken on more meaning in the wake of Oct. 7. It enumerates a myriad of bold and courageous wishes for the upcoming month, each beginning with the word “chayim” (life), which now evoke a new deep emotional response within me.

Standing in synagogue together with the community, I now ask God for:

A long life: I no longer take this for granted as I contemplate the precious souls we lost — including relatives, friends and students.

A life of peace: Though still in the midst of war, I pray for true peace to be achieved.

A life of goodness: Recalling the overwhelming solidarity of the war’s early weeks, I pray for a return to that spirit of unity.

A life of sustenance: For the displaced evacuees and reservists’ families struggling with trauma and their physical livelihood.

A life with awareness of heaven: That we should seek a rendezvous with God, even when He may appear to be hiding.

A life without shame or humiliation: I pray for Jews worldwide to walk freely without fear of attack.

I then ask God: If my prayers go unanswered, then please heed those more righteous: the soldiers, their spouses and children; the families of the hostages and the fallen; those forced to flee their homes. In their merit, may the upcoming month bring only goodness and blessing, with the safe return of our hostages, soldiers and everlasting peace.

Psalm 27: “Hope in the Lord but also be strong”

Shuly Rubin Schwartz is chancellor of The Jewish Theological Seminary.

I’ve always looked to Psalm 27 to guide me through this season. This psalm cuts right to the trepidation that the Yamim Noraim, the Days of Awe, conjure up in each of us. As the liturgy reminds us repeatedly, we are at God’s mercy; our prayers evoke vulnerability and expose our deepest fears.

Post-Oct. 7, the intimate first-person psalm reads differently to me. This year, the “I” captures not individual longings but rather the collective yearnings of Am Yisrael. We mourn the murdered and the captured, we feel abandoned by a world that has grown more receptive of antisemitic rhetoric and behavior, and we worry about the mounting consequences of a yearlong war with so many victims.

We yearn desperately for the release of all the hostages, a lasting peace that will enable Israel to thrive and the Palestinians to cultivate a home with dignity, and a global repudiation of antisemitism. Sadly, we also long for an end to internal communal division and to the distancing we feel from those whose choices differ from our own.

The soul of the Jewish people has been frayed in both body and spirit after this pain-filled year. But I take comfort in the psalm’s conclusion: “Hope in the Lord but also be strong, take courage.” As one people, we need to build upon our strengths and courage — physical and spiritual — and each do what we can to bring about the future we long to see.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.