It’s the very end of April 2024, and Passover has just concluded. But the senior staff at the Upper East Side’s Temple Emanu-El — one of the largest Reform synagogues in the world — are already sitting down to discuss the logistics for Rosh Hashanah services and events, six months away.

Known as the High Holidays, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services are the most attended of the year among the congregation’s 2,400 member households. From the beginning of Rosh Hashanah, which this year starts on the evening of Wednesday, Oct. 2., through Simchat Torah on Oct. 24, the majestic Romanesque Revival building at 1 East 65th St. will welcome some 6,000 people.

There’s a mind-boggling amount of preparation for the 20 services and events that will take place over the most significant days on the Jewish calendar, and there are tasks for every one of Emanu-El’s 125 employees, from maintenance workers to clergy. From ordering flowers to 40 hours of choir rehearsals to cleaning the 35-foot-tall organ pipes, the High Holidays at Emanu-El are, as deputy executive director Vivien Hoexter puts it, “our Olympic marathon” — except that, unlike the Olympics, which occur every four years, the High Holidays happen every year.

For a glimpse at exactly how, and how long, a large congregation prepares for its busiest season, the New York Jewish Week sat down with six key staff members at Temple Emanu-El to get an inside peek at what it’s like to prepare for the High Holidays at one of the best-known synagogues in the country. Keep reading for our “oral history” of how High Holiday services happen.

Interviews have been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Rabbi Joshua Davidson looks at the bima of Temple Emanu-El where he’s conducted High Holiday services as senior rabbi since 2013. (Julia Gergely)

Rabbi Joshua M. Davidson, senior rabbi: As soon as one set of High Holidays ends, I’m already making notes for the following year — sometimes it’s about things as simple as “that cue didn’t work,” or we need a better transition from this prayer into that prayer, or that service ran long. You have to remember all of those things while they’re still fresh in your mind.

As soon as Passover ends, the Temple Emanu-El staff come together to set the schedule of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services, as well as other events and programs during that period, including guest speakers, study sessions and a new members fair.

Cara Glickman, chief operating officer and executive director: The very first thing I do is confirm with Rabbi Davidson his vision — the services, the schedule, the basic outline of the event. That gives us a frame then we put all the things on top of that frame. It’s like a fine orchestra. We come together to create this very special and important experience, perhaps the highlight of our members’ year.

Cantor Mo Glazman: We have a musical team meeting in April to hammer out a rehearsal schedule that accommodates all these instrumentalists and singers. [The High Holidays] involve over 50 singers, three organists, multiple instrumentalists. It’s a huge musical team, in part because we do multiple services at the same time, and in part because each of these services have somewhat of a different flavor.

Vivien Hoexter, deputy executive director: We have an Excel grid that we work on for months to figure out exactly who should be outside the synagogue greeting people, who should be in the lobby, who should be putting down donation cards.

Throughout the summer — typically a quiet time in synagogues — preparations for the autumn holidays slip into high gear.

Glickman: I always say it’s “the storm before the calm.” We work very, very hard prior to the holidays. If you set it all up right, it’s very calm when you get to the holidays. You’ve really anticipated all the needs, all the circumstances. People know where they’re supposed to be when, all the supplies are in place, all the technology is humming, and so there’s a sense of order to it all.

Hoexter: We have cross-departmental meetings about once every two weeks, and then once a week, and we’re talking about things like, “What stuffed animals do we want to use this year for the young families services? How many do we need? Who’s going to order them?” Every summer, a company shines the images on our bronze exterior doors. This year, we also had the bronze around the five indoor elevators completely cleaned and shined up. Our maintenance team gives the floors a high-gloss polish, they shampoo the carpets.

Hoexter: We do a ritual called “the dig out,” where we get rid of everything we no longer need, from furniture that’s broken to prayer books that we no longer use that need to be buried. We have this huge building and you know what they say — any available space will be filled. This year we filled up a truck and a half of things to be disposed of.

Glazman, meanwhile, works with the musical team to develop a musical program that meets the moment, working with instrumentalists and a large choir, as well as three organists. Temple Emanu-El’s organ is the largest of any synagogues in the world, with 10,000 pipes ranging from the size of a pencil to nearly 35 feet tall.

Glazman: For our classical service, we don’t change that much of the music, but we still want to connect with people’s musical minds and souls for the moment of the day. These days that would be the State of Israel and antisemitism and Jewish identity. We ask our team, “How would the music reflect those needs?”

This year Glazman and his team put together songs that make sense of the attacks on Israel on Oct. 7 through the lens of High Holiday liturgy.

Glazman: For Rosh Hashanah morning there is a section of the liturgy that reads: “On Rosh Hashanah it is written, on Yom Kippur it is sealed; How many shall pass on, and how many shall come to be; Who shall live and who shall die.” This particular stanza of prayer inspired Leonard Cohen to write “Who by Fire.”

This year, I worked with a composer and colleague, Cantor Jonathan Comisar, to adapt “Who by Fire” as a reflective piece that asks those same liturgical questions with Oct. 7 in mind. In addition to lyrics like “Who in Kibbutz Be’eri? Who in K’far Aza? Who at Nachal Oz? Who in Netiv Ha-asara?” we include an excerpt from Rachel Goldberg-Polin’s eulogy, asking her deceased son Hersh: “Hersh, I ask your forgiveness. If there was something we could have done to save you … my sweet boy.”

Davidson uses the quieter summer hours to begin writing the two sermons he’ll give — one on Rosh Hashanah and one on Yom Kippur. Each sermon is about 25 minutes — around seven single-spaced pages. Rabbi Amy Ehrlich will deliver a sermon on Erev Rosh Hashanah and Rabbis Sara Sapadin and Sarah Reines will deliver sermons on Yom Kippur morning.

Davidson: In June, maybe July, I’m already thinking about sermon topics in a more precise way. I usually try to write one sermon addressing the events of the moment and how we as Jews might experience or approach them. That’s usually Rosh Hashanah. For Yom Kippur, I try to pick a theme which is much more personal, to help people through the challenges that life throws at them, beyond the challenges of the world around us, because we’re all on our own very personal journeys with loved ones and friends and health, and we need strength for that.

On Rosh Hashanah this year, Davidson plans to address the election, the Israel-Gaza war and antisemitism. On Yom Kippur, he plans to talk about “our responsibilities to ourselves and to others.” and the needs of finding balance to fulfill both.

Davidson: I read a lot of articles and books, and I read sermons of rabbis who wrote generations ago, because they always inspire me.

Davidson’s go-tos include “The Gifts of Life,” written by his father, Rabbi Jerome Davidson, and “Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow,” by Rabbi Jacob Rudin.

Davidson: Then I go about my own writing. When I have drafts that I think are worth anybody’s time, I show them first to my father, who was for 40 years the senior rabbi of Temple Beth El in Great Neck, New York and still the best preacher and sermon writer I know. And then my mom, who is brilliant in her own right, reads them. Then I make my edits as I need to. Then I send them to Rabbi Peter Rubenstein, for whom I served at Central Synagogue when I was first ordained, and he has a brilliant eye and mind as well, and he picks up on different sorts of things, and then I make those edits and then I read them out loud to my wife. She is the final judge and will let me know if things are clear or not.

In an ideal world, I try to write the sermons so that I have drafts a month before. Then I spend a month hammering at them, because I think the editing is the most important part of the whole thing. Then in the days leading up, I practice them from the pulpit, because sometimes when you read something and you hear it, you realize that it doesn’t work.

Mike Witman, the director of family and teen services, works with his team to create innovative programming for services for teens, families with elementary school-aged kids, and the young the young family service.

Witman: One of the things we’re trying to do at Emanu-El is create accessible moments for parents to model Jewish life for their kids. This is also an opportunity for families to see clergy as people that are accesible.

On Rosh Hashanah, we’re going to tell the story of creation, but we’re going to do it in a funny, fun, interactive way. We’re going to dress up in these huge, blow-up costumes. We found one for the sun and the moon, and light and darkness, and creatures of the sea and creatures on the land.

For Yom Kippur, we’re going to do a race between the tortoise and the hare — we’ve created our own skit for it and we are using the tortoise as a way for kids to recognize that on Shabbat and on Yom Kippur, the Shabbat of all Shabbats, it’s a time for us to really step back and try to rest and rejuvenate.

We’re going to bring a real tortoise into the sanctuary, and have a projection of hare bouncing around the room. We’ve partnered with Petqua, a neighborhood pet store on the Upper West Side. The tortoise is named George, and we have an exciting plan to bring him to life with the voice of our clergy. Families will have the opportunity to encounter him after the service.

George the Tortoise, who will be in the sanctuary on Yom Kippur for the family services. (Julia Gergely)

Witman’s team had also designed custom swag for the young families service, where he expects about 800 people.

Witman: We’ll be handing out plush tortoises to the kids with the message, “Slow down; you move too fast.” For the adults, we’ll provide Shabbat “cell phone sleeping bags.”

I don’t like to refer to our service as a production, but I do think production value is really important as you’re trying to take people on a spiritual journey. So it matters how you think about transitions, and our clergy do an amazing job of that, and our spiritual leaders do an incredible job of that. We really try to support them and lift them up in order to give everyone we serve meaningful and a spiritual experience.

For the communications team, mailings and emails about the High Holidays are planned during the summer. The department is also responsible for the livestreams of the High Holiday services, something the temple began during COVID-19. Last year, Emanu-El’s services had more than 600,000 views in more than 100 countries.

Bryan Limon, senior director, communications and marketing: There are a ton of emails. There are emails for requesting tickets, emails for getting RSVPs, emailing out the scheduling, emailing the requests for Yizkor [memorial service] — everything you can think of. We also remind people on social media. We meet with all of our stakeholders, from the Men’s Club or the Women of Emanu-El to the Young Families program to make sure that we have runway on their needs and we’re not sending out like 20 emails in one week.

Every year, we send a holiday card and gift to new members, if they’re in their 20s and 30s, we send out candlestick holders for Shabbat, and if it’s a family membership, they receive a round challah and some honey. This year, we decided to also send a High Holiday greeting card to all our members, so we custom designed and printed a really beautiful card with an embossed illustration of the Ark in the Fifth Avenue Sanctuary.

Some of the pre-High Holiday preparations are physical. Glazman, for example, spends time throughout the year strengthening his body and his voice.

Glazman: Part of vocal health is being in good physical shape — I love to work out a lot and lift weights and swim and run and all those things, because at the end of the day, you’re asking your body to do something for a prolonged period of time, and your body has to be there for you in a way that’s supportive and healthy.

I still train my voice twice a week. Similar to if you were a basketball player, you may want to do yoga and also learn how to sprint. It’s the same principle for a singer. I do these lessons which are just like acrobatics of the voice to stay healthy. I’ve been working with the same voice coach, Lenora Eve, for 20 years. She works with several cantors and Broadway singers and opera singers. She can tell everything about my day after about three notes of singing.

In the final weeks leading up to the High Holidays, the clergy, musical team and operations teams conduct “cue meetings” to do run-throughs of the services.

Davidson: I sit down with all of my colleagues, including the organists, and we go through the prayer book from the beginning of Rosh Hashanah through the last blast of the shofar on Yom Kippur. We mark in our books, ‘“Ok, this is where Rabbi Ehrlich is going to pick up,” “This is where Rabbi Davidson is going to pick up,” “This word, amen, is the cue for the singing of that song” and we go through it in great detail.

One of the challenges of this sanctuary is that the organist is up above the sanctuary, out of sight, while the rabbi is on one side of the bimah, and the cantor is on the other. So it’s impossible to elbow somebody and say, “You’re up.” So you have to have it all figured out, otherwise it would look like, “Wow, they really didn’t get it together in time.”

Glazman: The cues have to be clear. The sound engineers have to have a sense of what’s going to happen when, so they’re at the ready. Our livestream video team has to be aware of all the things happening and where all the prayers are in the prayer books so that they can simultaneously broadcast the service and make sure that the right words are popping up on the screen. It’s a multi-team extravaganza to get all of the departments ready for the production of the service.

Davidson stands at the bima of the main sanctuary. (Julia Gergely)

Davidson: All told, it probably takes six hours for us to go through all of these cues. This year, we were also working hard to try to figure out how and where to place into the context of the traditional High Holiday liturgy, prayers and meditations that allow people to reflect on the tragedy of Oct. 7 and what has occurred since, because obviously the High Holidays literally bookend Oct. 7 this year.

Hoexter: We actually create a guide each year for the maintenance team so they know what each setup is — where the musicians are going to sit, if we’re going to use clear glass podiums or wooden ones. The clergy is mostly up on the bimah — is there any point at which they’re going to come down off the bimah and would need a microphone when they’re off?

Glazman: The choir gets four three-hour rehearsals, and we layer in instrumentalists on top of that, and then I’ll meet with the organists privately for a few sessions. If there are people who are singing duets with me, we will rehearse separately. It’s somewhere in the ballpark of 40 hours of rehearsal.

Davidson: There are some services where we have a choir on the bimah, and other services where we have instrumentalists on the bimah. So sometimes the choir is up above with the conductor and the organist and the instrumentalists are down here, and they have to figure out how to stay in time when they’re not together, and by virtue of their not being together, the instrumentalists and the cantor actually hear them a split second after they’ve sung.

With services happening in two different sanctuaries throughout High Holidays, it’s crucial for clergy to know exactly where they need to be.

Davidson: On Rosh Hashanah morning, we have to cycle the people through and we also have to cycle the clergy through. There’s a service going on in the main sanctuary at 10 o’clock and then there’s service in the Lowenstein Auditorium at 10 o’clock. I preach in Lowenstein first, while the Torah is being read in the main sanctuary. Then we flip and I come into the main sanctuary and preach while the Torah, haftarah and shofar are being blown in there. There have been years where I’ve finished and I’m like, “Why didn’t the Torah reader come in yet? Am I going to walk in there and I’m going to walk in at the wrong time? Who’s going to be leading this service if I leave right now?” We don’t have walkie-talkies so we just have to work on it, and we try to time everything out, just to make sure it works.

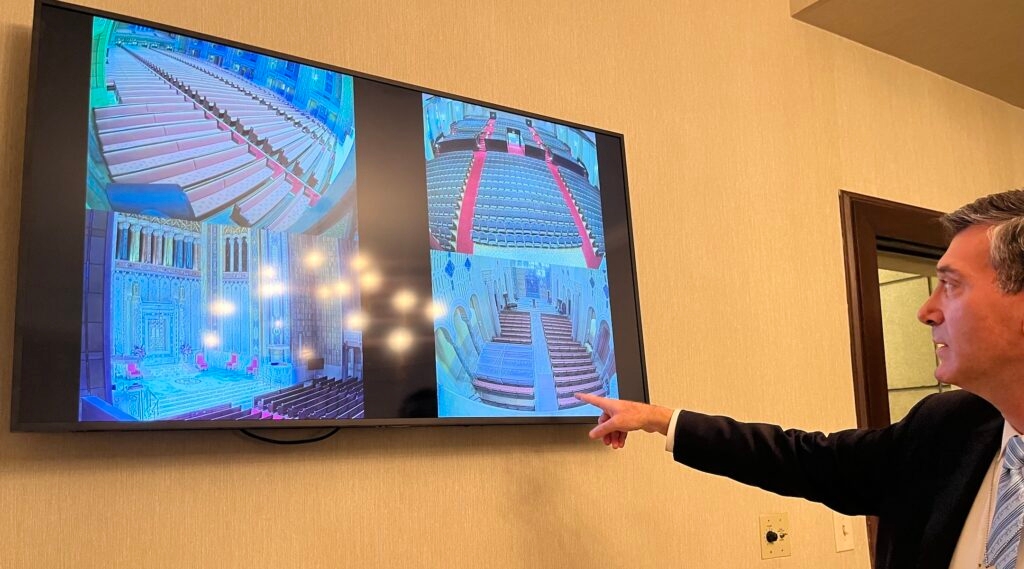

A live feed of the rooms streams in a small room in between the Main Sanctuary and the Lowenstein Sanctuary so clergy and staff can keep track of where in the service each room is while they run at the same time. (Julia Gergely)

In the main sanctuary on Fifth Avenue and the adjacent sanctuary at Lowenstein, members receive High Holiday tickets with assigned seats. Hoexter and Glickman work with the operations, membership and volunteer team to develop the best system for laying out personalized donation cards on each member’s seat on Rosh Hashanah. (Temple Emanu-El declined to share financial information with the New York Jewish Week, but according to their web site, an annual family membership starts at $3,000).

Hoexter: In our sanctuary, it’s a little bit like a Broadway show, in the sense that closer to the bimah the seats are more expensive because you have better sightlines. People who have assigned seats hold onto them for years, and sometimes they pass them to their children. We were founded in 1845, so we have a number of three- or four-generation families who are members of the synagogue.

On Erev Rosh Hashanah, the team of ushers has a 15-minute window to collect the donation cards from seats and place down new cards for the Shir Hadash service.

Hoexter: One of the things we talk about is how to do the laying down of the cards in a 2,500-seat auditorium to make sure that every seat has the right card with the right name. We have only 15 minutes between services to collect and put down new cards — we’ll have at least a dozen people putting down cards — so you can imagine it takes a lot of planning to do that quickly.

Keeping up adrenaline is an important consideration for Emanu-El employees during the holidays, and Glickman and Hoexter, who are in charge of staffing, make sure that the staff is taken care of.

Hoexter: We try to schedule the staff so that every single staff member has a break during the day on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, because some of our key staff, like our membership staff and our help desk, are running around and making sure that everything is going well.

Glickman: We don’t want people to have to worry about what they’re having for lunch, breakfast or dinner. All of the Jewish holidays start in the evening, so we’ll have a Rosh Hashanah evening dinner provided for our staff and our security team as well. We serve traditional foods that we would have in our own homes — kugel and chicken and brisket. The day of the holidays, we always serve breakfast and lunch, again just so everybody has easy access to stay nourished and hydrated. There’s lots of coffee and lots of water, so everybody keeps going. It’s a long day on your feet, seeing our members and dealing with small issues here and there, so hopefully it makes everyone’s day a little bit easier.

Hoexter: We definitely feed our staff members on Yom Kippur, for those that need it. Most of us find it extremely difficult to work without eating and drinking.

For the clergy, who do fast on Yom Kippur, fasting is not as big of an issue as one might think.

Davidson: Those of us who are leading services are operating on adrenaline. We’re just so focused on what we’re doing that I think we just kind of keep at it. For people sitting in the pews, I’m sure they feel the hunger pangs in a different way.

Despite all the hard work, the High Holidays remain a special time for the congregation’s clergy and staff.

Davidson: Looking out [at the congregation] on the High Holidays, maybe at the beginning for me, it was daunting — and I’m still always nervous, because one should be a little bit nervous when you do your work — but now I look out and I see faces of people who I’ve come to know and love and who shared some very wonderful moments with, and for some, some very painful moments with, so I’m not talking to a group of strangers here.

Mike Witman, Mo Glazman, Joshua Davidson and Sarah Reines with a confirmation class of teens at Emanu-El. (Courtesy Emanu-El)

Glazman: There’s a general buzz in literally every department, because this doesn’t happen without every single person’s help. Sometimes those of us on the bimah are the most “out front” for this by design, but literally everyone in this building has a responsibility that is critical to make this into something special. So the overall feeling is we have this buzz, this energy, this responsibility.

At Neilah, which is at the close of Yom Kippur, we’ve all been fasting and we’re at those waning moments where the gates of destiny for us are about to close, it feels to me like almost a mystical experience. Your body feels depleted and at the same time, completely energized. It’s a time where that intensity and desperation of prayer feels like not only I’m feeling it, but hopefully everyone else is as well, it’s unbelievable. It’s affirmation to me that what we’re doing matters, and it matters for everyone.

Davidson: It’s a tremendous amount of work, but there’s great camaraderie and joy in it. And then, when it’s all done, we look back on it and say, “Thank goodness we don’t have to do that for another year.”

My favorite moment, not just because the holidays are now done, but my favorite moment is at the end of Yom Kippur, when the shofar is blown. Because the tradition is that you’ve been renewed and reborn for another year. If you really stick it out till the end of Neilah, you’ve given yourself such a gift.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.