Jewish authors Shira Dicker and Don Futterman both grew up in Queens in the 1970s. In many ways, their memories are similar — attending the annual Salute to Israel Day Parade and rallies for Soviet Jewry; playing football on weekends in Flushing Meadows — but they also reflect childhoods spent in very different New York neighborhoods among vastly different Jewish communities.

Dicker, 63, who runs her own communications firm, recently published her first book, a short story collection called “Lolita at Leonard’s of Great Neck and Other Stories from Before Times.” A rabbi’s daughter, Dicker spent her childhood in Douglaston and attended North Shore Hebrew Academy in Great Neck and the Ramaz School in Manhattan. Her family moved to Forest Hills when she was 17.

Meanwhile, Futterman, 66, is the author, most recently, of “Adam Unrehearsed,” a coming-of-age novel about a Queens bar mitzvah boy that came out at the end of last year. Futterman grew up in Flushing — first in an apartment building on bustling Main Street, and then in a ranch house abutting the more suburban Queens neighborhoods of Bayside and Whitestone — and attended public school.

Both authors are appearing together in Manhattan on Tuesday night at The Society for the Advancement of Judaism on the Upper West Side for a discussion, “Two Kids from Queens: On Growing Up Jewish in the ’70s.”

“For me, it was a paradise of security and I was totally free,” Dicker told the New York Jewish Week about her childhood. “It was before the era of kidnapping. My parents, who were pretty much on top of my life, did practice benign child neglect, which I think all parents did. I don’t think they knew what we were up to. I remember going out on bicycle trips at the age of 7 or 8, [biking for] miles, getting lost and finding myself in Jamaica and having to find my way back.”

Futterman, meanwhile, recalls growing up on the 15th floor of a large apartment building. “You had this bird’s eye view of the world from up there and you could throw things down on the kids from 15 floors up,” he said. “It was very entertaining. My grandmother lived with us, she was the sweetest old lady in the world. When they would send people up to find out who these kids were, she would say, ‘There are no children here.’”

Both writers recall feeling a sense of “otherness” as kids: Growing up, Futterman recalls trying to manage his Jewish identity within the mixed community in which he lived; Dicker, meanwhile, longed to spend more time in secular culture, where feminism was ascendant and pop culture more vibrant.

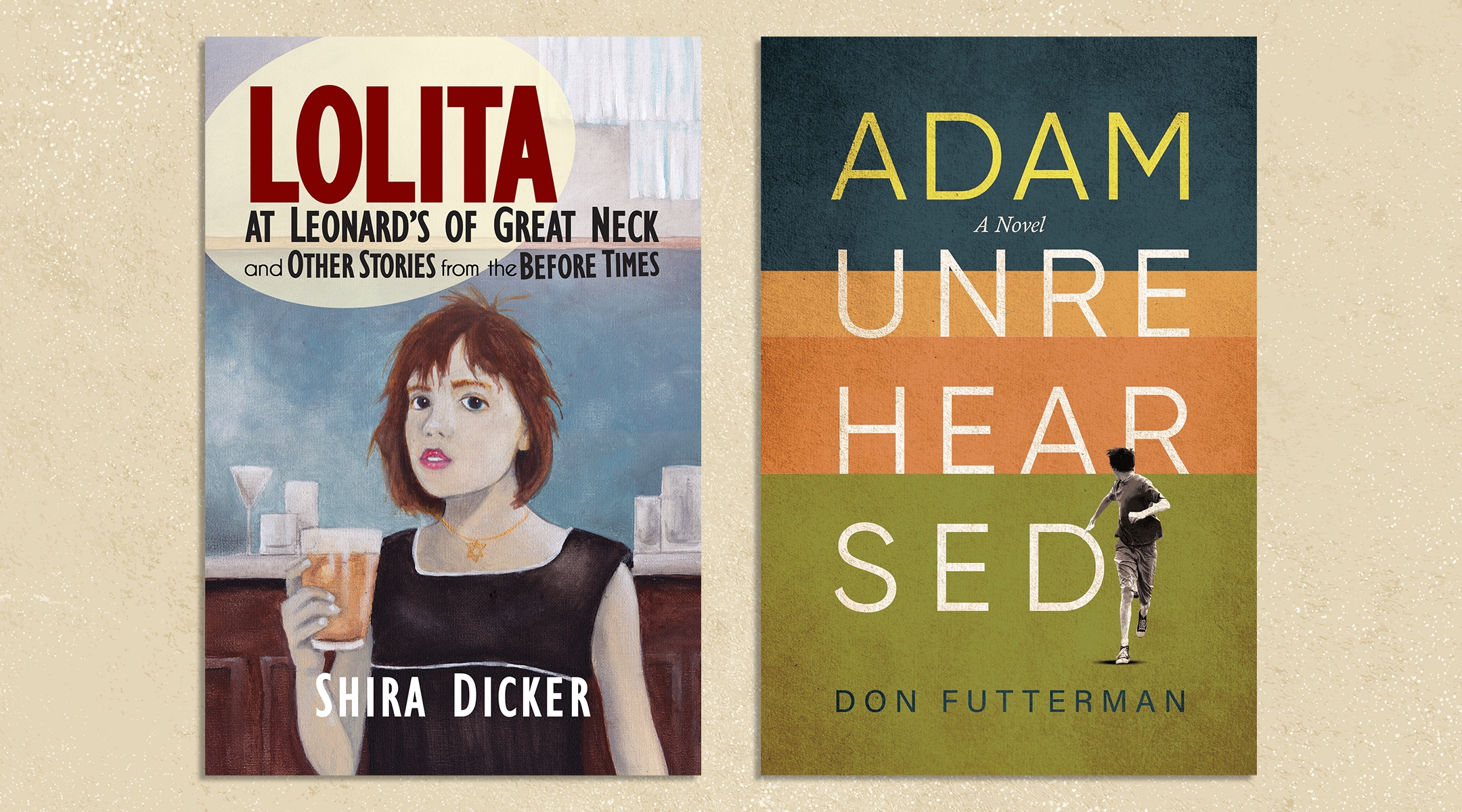

Two recent books that reflect the authors’ experiences growing up Jewish in Queens. (Courtesy Wicked Sons)

These experiences are reflected, both covertly and overtly, in the authors’ recent books. In her anthology, which spans four decades, Dicker’s female characters grapple with their self-image and emerging sexuality. In her first story, innocent 13-year-old Rebecca attends a bar mitzvah at Leonard’s — a popular Great Neck catering hall that both Dicker and Futterman frequented in real life — where she finds herself alone with her crush, a young (but nonetheless too old) male teacher.

In “Adam Unrehearsed” a 12- and 13-year-old Adam Miller struggles with who he is as a Jew in the months leading up to his bar mitzvah, while contending with societal ills like gangs and antisemitism.

Both writers have left their old neighborhoods. Dicker lives in Morningside Heights with her husband Ari Goldman, a journalist who himself has written memoirs about his Jewish life. They have three children: Adam, 40, Emma, 36, and Judah, 29. Futterman, meanwhile, moved to Israel in 1994; after settling in Tel Aviv, he and his wife, Shira, moved to Kfar Saba in 1997, where they raised their twin boys, Nimrod and Yaniv, 27, and daughter, Maayan, 21.

Futterman wrote his book, in part, because he wanted “to share some of his childhood with his Israeli children because it was so utterly different from theirs,” he said.

We spoke with the authors about their books, their early lives, and what it was like growing up in the so-called “golden age” of American Jewish life.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How do your books reflect your childhood and your Jewish upbringing in Queens?

Futterman: Like any kid, I found Hebrew school a burden. It was three days a week. On the one hand, I was the star of Hebrew school, on the other hand it’s like being Miss Subways — it’s not necessarily the crown you want. It was an alternate universe for me. I had a very mixed group of friends. It was like my other world. But it was a very warm place.

I grew up reading Philip Roth and, anywhere in American fiction, any place Hebrew school was written about, it was ridiculed and completely mocked. So I kind of wanted to show it differently and show the positive side of this experience without trying to prettify it. Clearly it turned off generations of Jews, so it wasn’t working, in that way it was catastrophic. On the other hand, there were always those bright spots, and the people who somehow found their way through that to something that was rich and meaningful and helped you and inspired you in your life as well. I was trying to capture that.

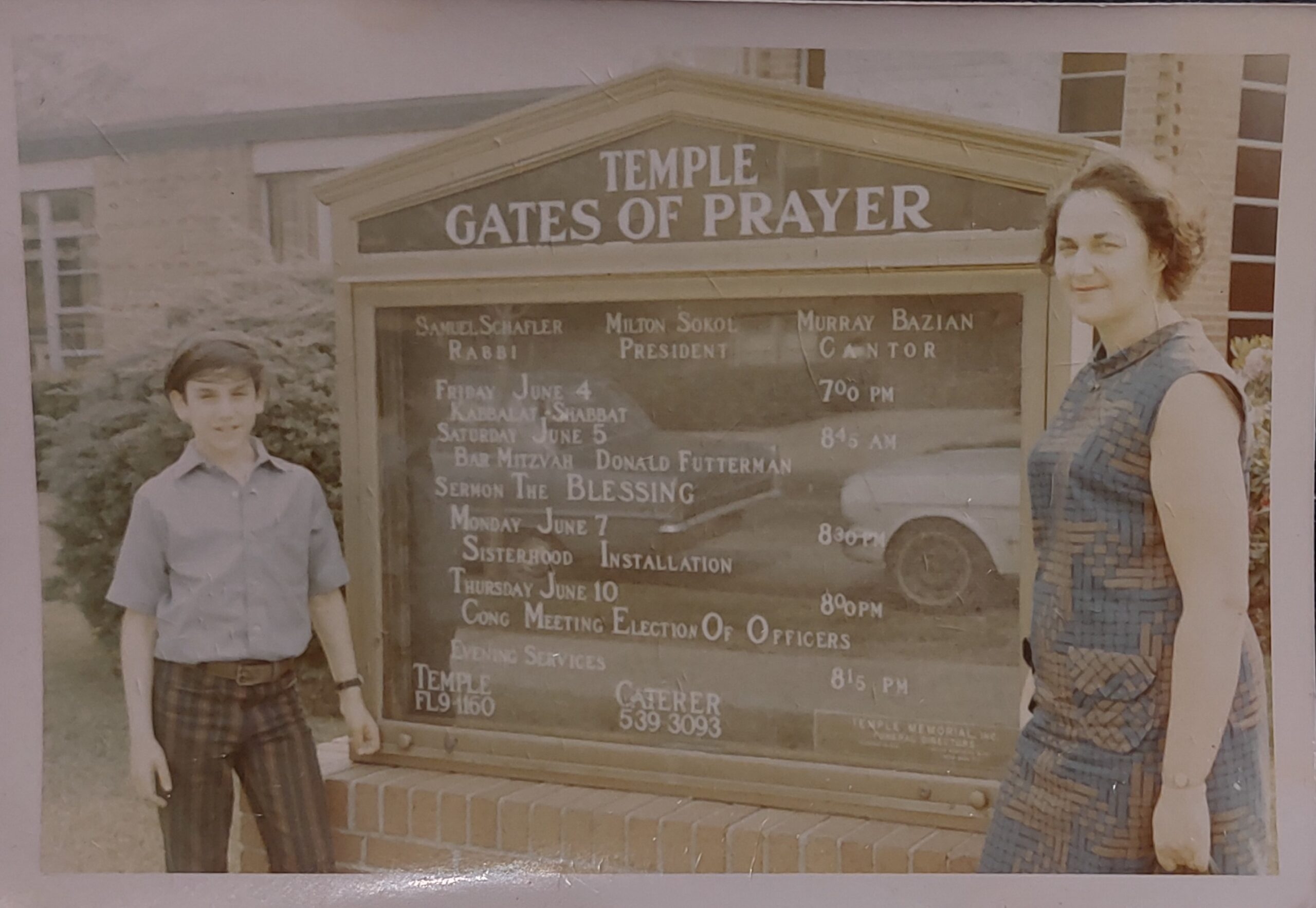

Don Futterman, left, and his mom, Ruth, ahead of his bar mitzvah at Temple Gates of Prayer in Flushing in 1971. (Courtesy)

Dicker: This is a work of fiction. The characters themselves are not stand-ins for me. Everything we do as creative people is a reflection that comes from the self, comes from the id. My stories have sparks, real-life sparks.

[In the short story] “Persephone’s Palace,” the 18-year-old girl has just come back from a summer when she ran away from a summer camp in Ojai, California, that her parents forced her to get a job at. Well, as it turns out, when I was that exact age, my parents forced me to take a job at Camp Ramah in Ojai. I did not want to be there. I set about finding a boyfriend, making him do all kinds of things. I left, I ran away. I did, very irresponsibly, bolt out on everybody, so the beginning of this story happened.

I was then at a diner [in Queens]. It was not Persephone’s Palace — it was called the Georgia Diner — and a businessman comes over to me. I see him staring at me the whole meal, and [he] tells me how beautiful I am and he’s enchanted and gives me his business card. He’s at the Hilton, room 1207. I have the card. That’s the spark. Everything after that point is fiction. It’s a “what if” story.

What was your relationship with your Jewish identity when you were growing up?

Futterman: The whole attachment to the Jewish world growing up in New York — it was a way to single myself out; it was a way to make myself different from all the other kids in my class. One of the things that was really special about me and my circle was that we took the Jewish stuff seriously and we were very committed to it. And at the same time we took the other stuff very seriously. We were very passionate baseball fans, football fans, Knicks fans. Very much part of American life — we didn’t look at it from the outside.

Dicker: Don, we were both differentiating ourselves, given our setting. I had nothing but disdain for the kids who hung out in the kosher cafeteria and I even mention that in the story [“Persephone”]. I had 12 years of this. I need to engage with life, with other people, with culture.

I think there’s autobiographical elements throughout. We both tried to recreate that atmosphere, that world, the places you would go. There’s a whole bunch of similar places mentioned in our books: That was our world.

Futterman: Queens was our little universe. In some ways it was very safe. The antisemitic incidents I mentioned in the book, some of them happened the same, some of them happened differently. There weren’t that many of them.

Are any of your characters like you?

Dicker: The character closest to me is Anna in “Persephone’s Palace.” Her struggle was she needed to get away from her parents, whom she loved, but they were clinging to her. That’s a conflict I had with my parents when I was an adolescent and I went to Queens College. I wanted to go away, but my parents wouldn’t let me. And they pointed to all the other Jewish parents in Queens who seemed to have this secret pact, like the devil worshipers in “Rosemary’s Baby,” that all their kids were going to go to Queens. That was a very, very big thing in my late adolescence.

Futterman: Adam has a lot of me in him. I’d say the character is a much more self-aware version of who I was at 12, partly because I was writing in a close third person. It’s not a first-person narrative, and there are reasons why I didn’t do it that way, but I was trying to look at the world through a kid’s eyes as he’s discovering the world, but still be able to make more sophisticated comments or commentary than a child.

Do you ever visit your old neighborhoods? How did they change?

Dicker: I go back all the time. I haunt places where I grew up. The Marathon Community Jewish Center [where Dicker’s father was the rabbi] first merged several years ago and that section of Queens became very Asian. I would come to visit and sit in the sanctuary. I got a call from the shul about a year ago that the building was finally being sold and they invited me to come and pick up my father’s bimah chair.

Futterman: I left home at 17 and never actually lived in Queens again, although I did visit my parents a lot. Temple Gates of Prayer was there just a few years ago, now the building’s gone and the community has been relocated. And it’s become a largely Asian neighborhood. There have been big waves of immigration, first the Koreans and then the Chinese.

Shira Dicker, third from left, with her mom, her sister and her father in their living room in Douglaston, Queens. (Courtesy)

A recent article in the Atlantic claims the 20th-century “Golden Age of American Jewry” — described as Jews’ “unprecedented period of safety, prosperity, and political influence” — as having come to an end. Does this resonate with you? Did your childhood feel like a “golden era” and do you think that it is over?

Dicker: Oct. 7 brought the sense of living in a Golden Age to a screeching halt. For me, I think I became aware, slightly after Sept. 11, that what I had lived up until that point was a blip and an exception to the rule. I was in the haze of just happiness. Everything was not perfect — we had conflicts, we had fights — but there was an overarching remove from the experience of Jews throughout much of history. I could’ve felt marginalized as the rabbi’s oldest daughter; [instead] I felt admired, not just in my Jewish community, but at large. In New York City, everyone admired Jews, and it was great to be Jewish. It was an aspiration. We were a social elite. There was no self-consciousness to Jewish humor.

Now look how radically everything has changed. Jerry Seinfeld can’t make shows without being heckled. I think it started to unravel before Oct. 7, but Oct. 7 gave permission to those who were thinking it to start thinking it loudly. I don’t think it’s all gloom and doom. I don’t know. I feel something has changed locally and globally. But I knew even before Oct. 7, that we lived something special.

Futterman: I see it a little differently and I think partly because I’ve been living in Israel for so long, and seeing American Jewry evolve from the outside, as someone who drops in occasionally, it’s very hard to have a real perspective of an event that is still going on. We’re still in this event, since the Hamas attack and hostages were taken and the horrific war in Gaza and in the north.

The era we’re writing about, I don’t want to imagine that period as better than it was. There were plenty of problems; there were refugees and people were struggling. I think the glory of that moment is that we grew up in the first generation that felt completely accepted and completely at home in America. And when our parents would say those things about being careful not to make a shanda for the goyim, be careful how you behave in public, don’t feed the antisemitic undertow, ever, we thought they were being paranoid.

We’ve reached the highest pinnacles of power in the United States of America: in the arts, in culture and in broadcasting. In all kinds of professional fields from which we were once excluded in our parents’ generation. I don’t know if the Golden Age is over. I think we’re facing challenges we thought were history. I don’t know where we’re going. A lot of it has to do with how American Jewish leadership reacts. And what Israel does influences American Jewish life and security as well, in quite dramatic ways.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.