“When a lady whistled at you on Allen Street, you knew she’s not calling you to a minyan!”

So goes a particularly illuminating quote from a lawyer named Jonah Goldstein, describing just how derelict life on the Lower East Side was in July 1913, when gangs, pimps and assorted crooks ran rampant in the neighborhood.

In his new book, Jewish lawyer-turned-author Dan Slater details the immense scale of crime in the neighborhood at the turn of the last century, where famed Jewish gangsters like Meyer Lansky, Lefty Rosenberg and Dopey Benny got their start. But he doesn’t stop there.

In “The Incorruptibles: A True Story of Kingpins, Crime Busters, and the Birth of the American Underworld,” Slater spotlights a group of wealthy Jewish reformers uptown who waged war on the Lower East Side’s pimps and gangsters. The shocking tale is largely forgotten by American Jews today, even if it’s also part of the dramatic backstory behind legacy Jewish institutions like the Educational Alliance and the American Jewish Committee.

“I’ve been a big reader my whole life and this stuff was new to me,” Slater, 46, told the New York Jewish Week, “so it must be new to other people.”

“The Incorruptibles” describes the tactics employed by Jewish clergy, civic activists and law enforcement officials to clean up the Lower East Side, including an undercover stakeout to document prostitution at a gritty hotel and one of the first uses of an NYPD wiretap to capture a murder suspect involved in the underground gambling scene.

From the late 1800s to the 1920s, Jewish residents of Manhattan inhabited two vastly different worlds. The affluent, assimilated German Jews mostly lived on the Upper East Side, where many lived in luxurious mansions and summered in massive country estates. Meanwhile, their more recently arrived brethren from the Pale of Settlement lived below 14th Street on what was referred to back then as simply “the East Side.” The immigrants struggled to make a living in crowded, impoverished conditions that inevitably bred disease, vice and crime.

“Today we don’t think of ourselves as Russian or German, we just think of ourselves as a Jewish-American,” Slater said. “But back then that distinction meant everything.”

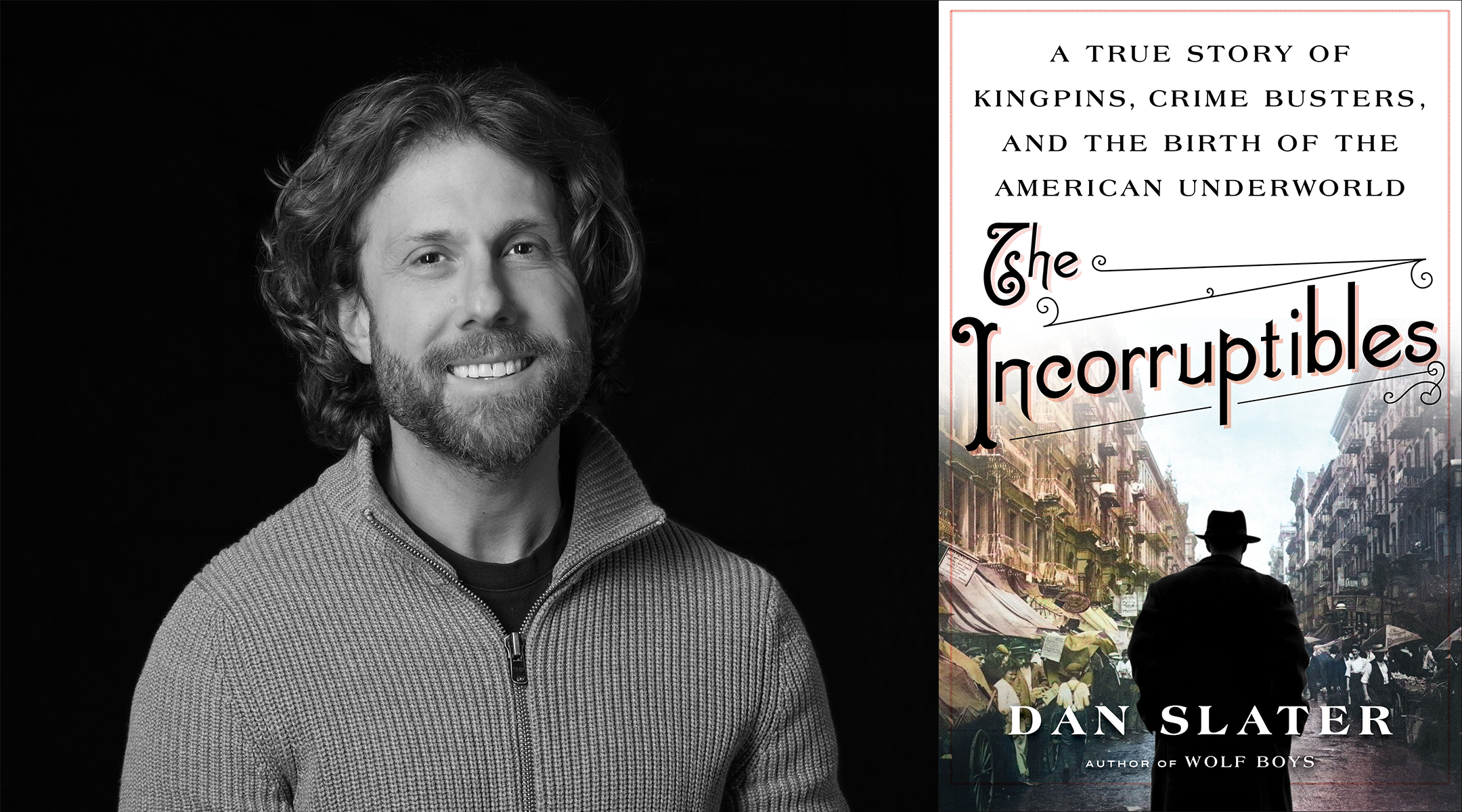

Author Dan Slater, left, and the cover of his new book, “The Incorruptibles: A True Story of Kingpins, Crime Busters, and the birth of the American Underworld.”

As the book details, the scope of prostitution on the Lower East Side in the early 20th century was greater than some historians have chosen to admit. (“Communities struggling for survival seldom rush to announce their failures,” Irving Howe wrote in his 1976 book about the era, “World of Our Fathers.”) There were brothels above, below and next to synagogues. They were also situated next to schools, soup kitchens and wedding halls. There was even a fraternal group of pimps on the Lower East Side incorporated under New York State law: The Independent Benevolent Association supplied members with employment insurance and burial plots. The Forward estimated in the early 1900s that close to 4,000 Jewish women went missing from New York City each year, many of them, ostensibly, to a life on the street as sex workers.

Despite all these sordid details, Slater feels that “The Incorruptibles” is ultimately a story of hope. That’s because it shows a community taking matters into its own hands in order to create a better future for all its members, he said.

“What you had was the Germans spending a ton of money to elevate the refugees to provide all these services that were not yet available to the poor because there was no welfare net yet,” Slater said, noting that federal income tax wasn’t imposed until 1913. “The wealthy didn’t even pay taxes. So, anything that was going to be done for a poor person would have to be done based on the good will and benevolence of a wealthy person. And fortunately, these German Jews, for whatever reason, felt this moral imperative to do whatever they could do.”

Well-heeled Jews who had already formed the American Jewish Committee to represent their interests joined with an alliance of downtown organizations to form the Kehillah, a clearinghouse to “study and ameliorate [the] social, moral and economic conditions” of the city’s Jewish poor, according to its 1914 charter. The organization, as Slater points out in the book, was an outgrowth of the age-old tradition of self-governance in Jewish communities in ancient Israel and afterwards in Europe.

The Kehillah enlisted people like investigator Abe Schoenfeld, a Wall Street lawyer named Harry Newburger and Rabbi Judah Magnes, who was spiritual leader of Temple Emanu-El, the Reform congregation on Fifth Avenue. The fiery rabbi was not pleased with what he deemed as his congregation’s lack of empathy for the hardscrabble lives of the Lower East Side Jews and eventually went to work for the Kehillah full-time. (Magnes later moved to Palestine and co-founded Hebrew University, serving as its first chancellor.)

The Germans who funded and were active in the Kehillah included Jacob Schiff, the investment banker who was dubbed “the Jewish J.P. Morgan” by the New York Times, and his son-in-law Felix Warburg, a member of the oldest banking family in Europe. (Warburg’s home on 92nd Street and Fifth Avenue now houses the Jewish Museum.) Other wealthy uptown German Jews included the Ochs family, which owned the New York Times, and the progenitors of future Wall Street powerhouses named Goldman, Sachs, Lehman and Solomon.

A milk depot dispenses bottles of pasteurized milk for pennies on the Lower East Side sometime around the turn of the 20th century. (Courtesy Dan Slater)

“It was quite a crowd and they partied, they lived it up with all that untaxed wealth,” Slater observed. “Those mansions they lived in uptown were no joke: vacation homes on the Jersey shore and in Maine; yachts and horse farms. It was pretty insane.”

Nevertheless, out of a combination of self-interest and charitable impulse they funded an asylum for orphans, provided free healthcare for the poor and created, in 1889, the Educational Alliance, a settlement house for newly arrived East European Jews. Financing the reform effort on the Lower East Side, however, “was always kind of hush-hush,” according to Slater.

Despite the assistance from their uptown brethren, to some degree, the Eastern European Jewish immigrants themselves were also responsible for turning the neighborhood around, Slater said.

“The immigrants had not lived in a free world for centuries,” he noted. “They had lived under severe oppression, survived massacres, adjusted to laws that restricted which professions they could pursue, laws that pushed them into crime. When they arrived on the Lower East Side, even though it was a ghetto with many problems, it was still a country where, theoretically, they could do anything.”

The one thing the uptown and downtown Jews did have in common was they both left observant Judaism.

“The children of the immigrants [downtown] saw [Judaism] as an old thing. They wanted to become American, they wanted to assimilate,” Slater said. “They didn’t want to be involved in some fusty religion thing and that was what united a lot of them with the German Jewish uptowners because the children of those people were the same way.”

Slater — whose previous book was 2016’s “Wolf Boys,” a true story of two American teenagers who served as assassins for a Mexican drug cartel — spent seven years researching and writing “The Incorruptibles.” That included reading through transcripts of the trial of seven members of the United Hebrew Trades, a federation of Jewish labor unions, for the murder of a strike-breaking Jewish tailor. (They were acquitted.) He also had a translator comb through the 13 Yiddish newspapers published in the Lower East Side, as well as unpublished volumes of the Yiddish autobiography of Abe Cahan, founder and editor in chief of the Forward.

A crime scene photo from the 1920s shows the body of a “maker of men’s shirts” who allegedly resisted union demands. (New York City Municipal Archives)

The book also benefits from Slater’s personal collection of period photographs purchased during online auctions of the Brown Brothers Collection. A valuable collection of hundreds of thousands of pictures dating back to 1904 that included photos of slums, immigrants and crime scenes, the images were auctioned off one at a time and Slater bought 700 of them.

“It was just amazing. All these characters and episodes and incidents that I’ve been researching and writing about like the horse poisoners– all of a sudden [they’re] in front of me on my computer,” Slater recalled. “I was seeing original and beautiful photographs of these very things and I was, like, ‘Oh, my God! This stuff is real. There it is.’”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.