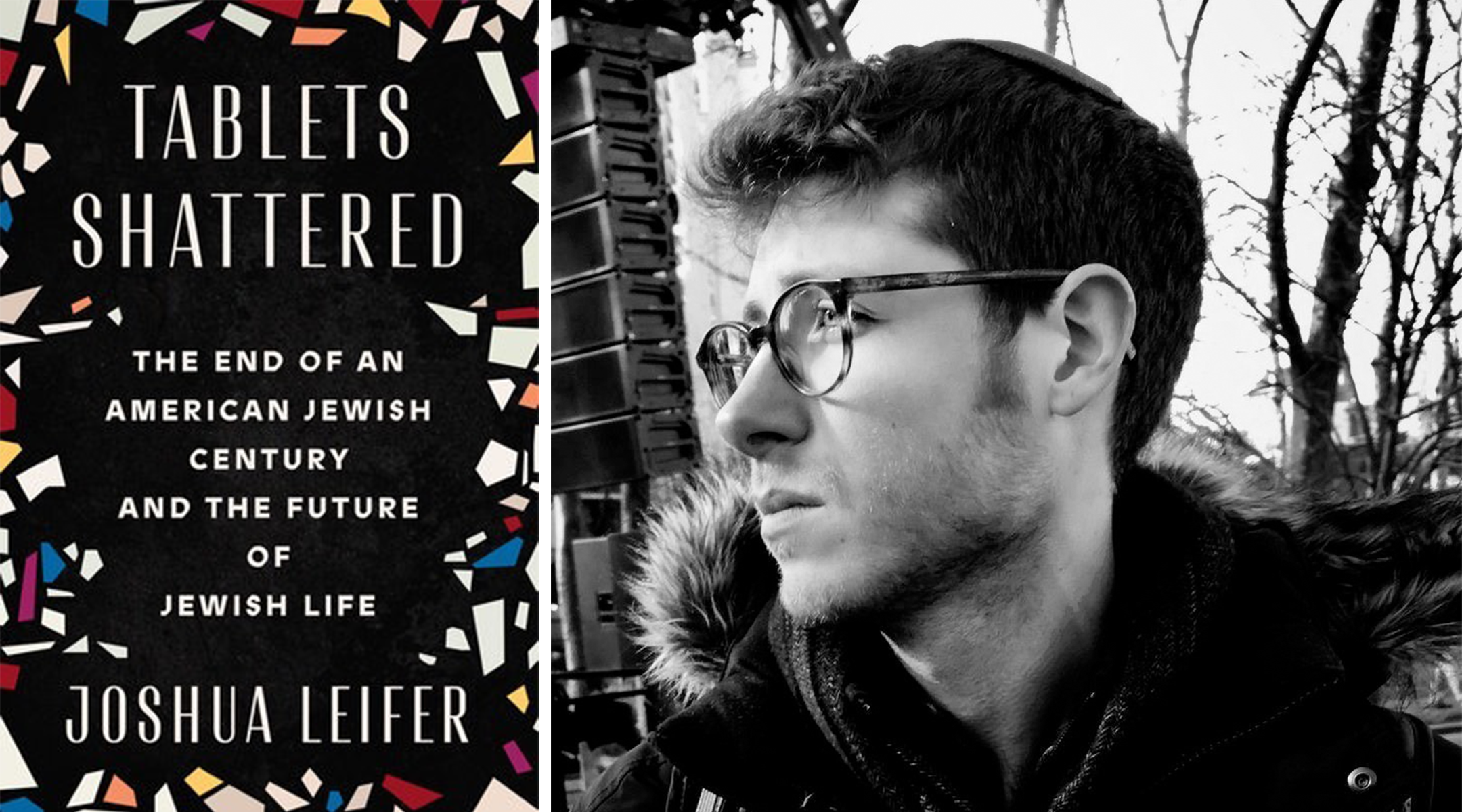

Joshua Leifer suspected that his new book about the history of American Jewish identity might challenge some on the pro-Palestinian left, but he never expected to be cancelled. After all, he is himself a high-profile Jewish progressive whose critiques of Israel have appeared in the left-wing publications Jewish Currents, Dissent and Israel’s +972.

If anything, he braced for criticism from the Jewish mainstream, which, as he writes in “Tablets Shattered: The End of an American Jewish Century and the Future of Jewish Life,” has been known to quash dissent in the name of a pro-Israel “consensus.”

But when objections from an employee at a Brooklyn bookstore led to the cancellation of an event featuring Leifer — the employee complained that the moderator, Rabbi Andy Bachman, was a “Zionist,” turning a normative position among American Jews into a disqualifying slur — Leifer’s book became a cause célèbre. The incident also represented in fractal form many of the themes of the book: A yawning gap between the Zionist Jewish mainstream and young activists who view Israel as a pariah. An inability of some to talk about Israelis and Palestinians without embracing the binaries of good and evil. And, reflected in the autobiographical sections of the book, Leifer’s attempts to reconcile his deep connection to Judaism with his disappointment in a Jewish state that he believes has become increasingly authoritarian and extreme.

“We are caught between parts of an activist left demanding that we disavow our communities, even our families, as an entrance ticket, and a mainstream Jewish institutional world that has long marginalized critics of Israeli policy,” Leifer wrote this week in The Atlantic, about the bookstore cancellation. “Indeed, Jews who are committed to the flourishing of Jewish life in Israel and the Diaspora, and who are also outraged by Israel’s brutal war in Gaza, feel like we have little room to maneuver.”

“Tablets Shattered” is a history of the social and political priorities of American Jews since the early 20th century, and how they shifted to reflect the crises and opportunities of their day. Chief among these shifts is the central role Israel came to play in the Jewish imagination and in communal politics, often eclipsing other homegrown issues and challenges.

Leifer, 30, also writes about how younger Jews no longer accept Israel as an organizing principle for their Jewish lives, and are looking for alternatives that feel authentic to their Jewish, liberal selves. And while Leifer aims most of his criticism at the Jewish establishment that kept dissenters at arm’s length, he has harsh words for Jewish progressives, especially since Oct. 7, who are “callous” about the lives of fellow Jews who happen to live in Israel.

Leifer also tells his own story — a New Jersey kid who attended a Solomon Schechter day school through sixth grade; an alumnus of a prestigious Israel program for American high schoolers; a Jewish student activist at Princeton; a member of IfNotNow, a group that calls on American Jewish organizations to end their “support for the occupation”; a writer who reported on anti-government and pro-Palestinian demonstrations in Israel.

Leifer told me he calls himself a “connected critic,” political philosopher Michael Walzer’s term for a dissenter who is deeply attached to the target of his criticism.

“We are part of the community,” Leifer said of Israel critics like him. “We come from the heart of the mainstream Jewish community, and we want to call that community into account for failing to uphold the values it claims to profess explicitly.”

Leifer is currently pursuing a PhD at Yale University; “Tablets Shattered” is his first book. Currently living on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, he’s considering a return to Tel Aviv with an eye on eventually splitting his time between Israel and the United States. On Thursday, we spoke about his Jewish upbringing, the mistakes made on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian debate, and what he’s learned about obligation from his wife’s haredi Orthodox family.

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

I want to start with your own personal evolution — a day school student in New Jersey who was disillusioned precisely by things you saw in Israel as a teenage visitor. What messages did you absorb about Israel growing up and how were they dispelled by what you saw in the country?

Israel was the glue, the core and the lens through which Jewishness and Jewish practice was refracted. At school, every form of religious observance that we did had some kind of connection to Israel. Many of the teachers at school were Israelis, the children of Holocaust survivors or survivors themselves, and people who had fought in Israel’s wars. It was a super-immersive, Israel-connected community.

But that also meant that the more that I encountered Israel, the more I came to see its faults. I was already in the process of a kind of ideological transformation when I went to Israel for my sister’s bat mitzvah, which was held at the egalitarian side of the Western Wall. Already then I was struggling with the news that I was reading, including in Hebrew.

Israelis set up a tent city on Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv in protest of high housing prices, Aug. 10, 2011. (Liron Almog/Flash90)

So this would have been in your mid- to late teens?

I was 17, and I had already developed a pretty strident left-wing critique of Israel, not in an anti-Zionist way, but in a kind of anti-occupation, Noam Chomsky informed way. I went on the Bronfman Youth Fellowship as a high school senior [when Bachman was a teacher on the program], and the encounter with Israel there was very powerful in lots of ways. One is that the more you encounter real Israeli society, the more you realize it’s flawed, just like any other society, which in some ways was a heretical thing to say coming from a community where Israel was so idealized.

The other thing that happened was that I was there during the 2011 social protest movement, and I walked among the incredible tent city that had been set up on Tel Aviv’s Rothschild Boulevard [to protest the high cost of living]. That was my first encounter with a politics that was Jewish, Israeli and also left-wing and to which I had never had access before.

That continued during my gap year before college at BINA, the secular yeshiva, which plunged me directly into Israeli progressive activist society. I lived in South Tel Aviv. I was immediately going to protests against the deportation of the Darfurian and Eritrean refugees. This was 2012, at the peak of the refugee crisis. I started to go into the West Bank a lot on tours with [the anti-occupation group] Breaking the Silence, and then with activists doing what they call “protective presence” at Arab houses slated for demolition in East Jerusalem. I became an activist. I was very involved in the creation of a group that still exists today in Israel called All That’s Left, which is an anti-occupation collective.

So at this point you are very, very critical of Israel’s control and treatment of Palestinians in the West Bank, and of the social inequities built into Israeli society. How far did you take it? Were you prepared to sever your relationship with Israel, and ask yourself why you were so invested in a country whose values you didn’t share?

There was a time when that happened. I came back to the States after my gap year before college, and basically after the first year in college, in 2014, Operation Protective Edge [Israel’s third major conflict with Hamas since 2008] and I got swept up in the activism. I was involved in different kinds of activist initiatives in college and started a group called the Alliance of Jewish Progressives, a way to give space for Jewish students on campus who, for political or identity related reasons, weren’t finding their home at Hillel.

The paradox is, the more you do these sorts of things, the more you get attached to the thing that you’re criticizing. So at a certain point, I said, “Well, I’m spending all my time talking about Israel and arguing about Israel in college. I probably should just go back.” I went back after I graduated, which is when I worked at +972 Magazine as an associate editor between 2017 and 2018, and it was during that year that I became the most radical I had been. Reporting daily on the occupation, being exposed to that level of both Israeli violence and Palestinian suffering — I don’t think I ever contemplated being able to disconnect from Israel, because my Jewishness was so Israel-centric. But I did invest more time in traditional textual learning in part because I was looking to ground my Jewishness in something other than Israel.

You write about this in the book as a period of “gradual disillusionment,” in which you and other critics of Israel’s control of the West Bank were beginning to doubt the future of liberal Zionism, which was predicated on a two-state solution.

I began to seriously contemplate what it would mean if a two-state solution was not going to happen. It seemed to me that the settlements were there to stay, and that there wasn’t ever going to be the political will to remove them, and that those of us who were attached to an Israel that could be democratic were going to have to face a really difficult reckoning with what happens if this place can’t be democratized. I had an argument with Michael Walzer in the pages of Dissent in 2019 that’s probably the closest I came to a position that some people call anti-Zionist, in that I argued that values should take precedent over an a priori commitment to one or two states. But I’m not an anti-Zionist and never identified as one publicly. I was never a person who thought Jews aren’t a nation, or Jews don’t have the right to self-determination.

In your book, you are critical of anti-Zionists, especially since Oct. 7, accusing many of a “cruel disregard for the lives of Jews in Israel” and harboring “fantasies of turning back the clock” to a time before there was a Jewish state. Why did you feel the need to call out putative allies on the left?

Even in my most strident and foundational critiques of occupation, I always was attached to the idea of a connection and mutual responsibility with Israeli Jews and feeling part of a broader Jewish collectivity. I think it’s wrong to say, “Well, those Jews over there, we are so disgusted by what they’re doing that we can’t have anything to do with them. And not only can we have nothing to do with them, but that whatever happens to them is probably justified.” That’s a morally reprehensible view, even if I can understand it at a kind of visceral, kishkes level.

There’s also a contradiction, because Jewish left-wing activism is based around a certain kind of Jewish identity politics. It presupposes a Jewish collectivity, but then it’s a Jewish collectivity that’s limited, basically, to America. That doesn’t make much sense.

Members of the advocacy group IfNotNow cover their eyes at a protest in Brentwood, California, Oct. 19, 2023. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Let’s widen the lens a bit, as your book does. Your book deals in depth with a shift in Jewish communal priorities, from what the immigrant generation and their children held approximately up to the Six-Day War of 1967, and a new set of priorities that developed in the wake of Israel’s lightning victory and other social upheavals. You describe it as an inward turn, from a more universal politics — of labor unions and civil rights and intergroup relations — to one in which Jewish organizations no longer felt the community had an ”obligation to care for their non-Jewish neighbors.” What is your evidence for this shift?

Coming out of World War II, into the ‘50s and ‘60s, Jewish organizations, both for reasons of self-interest but also out of genuine commitment, often framed their goals in terms of benefiting the greater good. We think about the Jewish participation in the early stages of the civil rights movement and the elimination of barriers to discrimination and restrictive covenants — it was always done in the interests of all people in the United States, or in the interests of democracy or the interests of equality. In the book I write about Rabbi Joachim Prinz [of Newark, New Jersey, who spoke at the 1963 March on Washington], an exemplar of this kind of Judaism.

After the Six-Day War, and also with the rise of what we today call identity politics, it became possible for American Jews to speak about Jewish interests explicitly. The neoconservatives were really at the vanguard of articulating what this would mean politically, linking the defense of Jewish interests with the defense of America. And then there’s the Soviet Jewry movement, which juxtaposed the Soviet Union, with its structural antisemitism, with the freedom and success that Jews have in America. Out of the Soviet Jewry movement, a new cohort of American Jewish leaders emerges, and they are shaped by what a lot of people called the inward turn of the 1970s, away from the universalist rhetoric and towards a defense of Jewish interests. The [late educational theorist] Jonathan Woocher called this “survivalism,” in that all of the energies of Jewish life are now oriented around the protection and defense of the Jewish people, whether in Israel against the threats that it faces militarily, or in America, against the threats posed by intermarriage, by antisemitism, by critics of Israel.

Still, many of the threats identified by the “survivalists” were very real, Israel’s enemies were legion, and there was the sense that if Jews didn’t speak up for their own self-interest, no one else would. I don’t want to ask you to be the voice of your generation, but what is it about this “survivalist” Judaism that no longer speaks to people, let’s say, your age and younger?

It’s a good question. There are demographic realities and there are political realities that have challenged survivalism. Israel has gone from being a moral exemplar and an encapsulation of American Jewish values, to being a source of shame — a much more right-wing and much more religious place than it was. A lot of young American Jews, especially those who grew up outside the Orthodox world, feel they have very little in common with Israel or very little to be inspired by.

I’m 30, which means I am old compared to the college activists who are really being mobilized [since Oct. 7]. I don’t remember the hopes of the Oslo period, I was 1 when Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated. I grew up post 9/11, post-second intifada, when Jews were doubling down on the inward turn. But people who are in their 20s now were born after the second intifada. Not only do they have no recollection of that period of Israeli vulnerability, they also don’t have any recollection of the hope of the Oslo Accords. They only know [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu, and Netanyahu is Israel. I don’t think it occurs to them that Israel could or was different at any point

And then there were the social movements and the upheavals that have happened since the financial crisis [of 2008]. For a generation of young American Jews that made them more interested in being in solidarity with marginalized people. Black Lives Matter has had a huge impact on American Jewish activism. If anything, I think it is remarkable that there are so many American Jews, despite all of these things, who want to be Jewish in public and who want their Judaism to be relevant to them. They might not know where to start.

In that regard, and feel free to disagree with me, your book takes a surprising, small-c conservative turn when it comes to religious practice. You write about how your own religious and communal practice — keeping Shabbat, donning tefillin — has become more important to you, and you call on fellow activists to take on a Judaism that is more traditional, embrace obligation and intentionally distance themselves from the mainstream of American cultural life. How did you arrive there?

In academic terms, I think I was trying to develop a kind of left communitarian politics from a Jewish perspective. I think that critique emerged in part out of living in the progressive Jewish world for a long time and, through my wife, who grew up in Lakewood [a haredi Orthodox town in central New Jersey], having been thrust into the thickness of an obligated community. I was also always sensitive to a certain irony that, in the activist world, we’re harsh critics of America and of American capitalism, but we live the epitome of the kind of life it offers by identifying with consumerism, worshiping individual choice and celebrating self-gratification.

Progressive secular Jews are infuriated by this. They ask how I could be inspired by praying with, you know, homophobic misogynists who justify an oppressive patriarchal society. And because the book argues for obligation, they think it rejects the huge changes in gender and sexuality that have unfolded in liberal Jewish life. But what the book asks is if we can build communities that are obligated without giving up the values that we care about: feminism, inclusion, LGBT rights, anti-racism, opposition to the occupation. Many people on the more progressive side of social issues aren’t interested in that reconciliation, but I hope the book is a starting point.

Marchers call for the release of hostages in Gaza at the annual Israel parade in New York City, June 2, 2024. (Luke Tress)

Tell me about your experience of Oct. 7 and its aftermath — your book was largely written and researched before then, but how did the war and the various reactions either reinforce or undermine the ideas you’d been forming in writing your book? You write about the Jewish left facing and failing a serious test. What was the test and how did they fail?

I handed in the manuscript in the week before Oct. 7, and went back and changed or rewrote about 20,000 words. The critique of where some of the Jewish left went was not in the book at all.

I felt the task of connected criticism was trying to change the politics of the American Jewish community. And then it seemed to me, in the wake of Oct. 7, that idea was completely dropped in favor of a certain kind of deference to more hardline, radical Palestinian positions. I realized that things I thought didn’t need to be said actually had to be said, for instance, that both Israelis and Palestinians aren’t going to go anywhere, and it would be unjust to require either one of those peoples to be forced out of the land in which they’re living. I thought that that was a given on the left, except for a hard core of territorial maximalists who negated Israel’s right to exist. But it wasn’t the dominant tenor of progressive politics until very recently.

One indication of this is the way the term “occupation” has disappeared from the conversation. We went from talking about ending Israel’s military occupation to ”liberating Palestine.” I don’t think it’s wrong: Palestine should be free in the sense that the Palestinians deserve a state and self-determination, but almost overnight the litmus test for progressive politics on Israel became supporting the dismantling of Israel. That took me by surprise.

You also write that the organized American Jewish community failed a test, “even more spectacularly.” How?

I think there was an opportunity with this war to learn from past mistakes and to not close ranks and to not give in to a kind of nationalist hysteria that’s intolerant of dissent, and that didn’t happen in a lot of places. I can be sympathetic as to why, because of how afraid and attacked people felt. But it’s depressing to be around people who say repugnant things about Palestinians or say they don’t believe there are innocent Palestinians, the way some on the far left will say there are no Israeli civilians. It’s demoralizing to see the way these two discourses have mirrored each other. The cheerleading for the war has been very depressing, and that’s the tenor of a lot of mainstream Jewish spaces.

What had you hoped to see?

I think that the Jewish community could be empowering people in Israel who were trying to challenge the Netanyahu line. If we’re actually serious about bringing home the hostages, then we should support Joe Biden putting more pressure on Netanyahu to reach an end to the war. And it drives me crazy, because I think it’s an abdication of responsibility that the organized Jewish community has the power to actually move the needle on these things, and it’s not using that power. Instead, it has enabled Netanyahu to extend this war that’s had hugely destructive consequences already and potentially greater ones to come.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.