By day, Yitzchak Meyer Twersky is an IT specialist for a healthcare company who lives in the Kew Gardens Hills section of Queens.

But in his free time, Twersky, 59, who is known as Yitz, has become the world’s leading authority on the globe-spanning Twersky rabbinic dynasty — one of Hasidic Judaism’s most prominent families, and his own.

The family, which dates to 18th-century Ukraine, boasts tens of thousands of members around the globe, and Twersky has spent the last 37 years researching, documenting and preserving everything he can learn about them.

The result: “The Twersky Dynasty,” a 522-page coffee table book published by Menucha Publishers, a Brooklyn-based Orthodox press, came out earlier this year. Rich in photos of family members, historic synagogues and ritual objects rescued from Ukraine, the book details the history of a clan whose descendants have left a mark on Hasidic Judaism and in fields as varied as the law, addiction treatment, journalism and acting.

To this day, the family maintains an outsized influence even among those not named Twersky: In 2017, Yitz Twersky conducted a study with amateur genealogists Jeffrey Briskman and Jeffrey Mark Paull, who studied hundreds of Y-DNA tests submitted by men in 31 countries to establish the genetic signature of the Twersky dynasty’s founder. They discovered that nearly every major Hasidic sect today — including the Belz, Bobov, Lubavitch, Satmar, Stolin and Vishnitz — is led by biological descendants of the family’s patriarch.

“The Twersky dynasty is still important today because there are currently thousands of Hasidic people under the leadership of the Twersky rabbis,” Shmiel Gruber, a 49-year-old rabbi who researches Hasidic history, told the New York Jewish Week.

The family tree begins with Menachem Nachum Twersky, who was born in 1730 and became a disciple of the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidic Judaism. It extends through more than 300 Twerskys who arrived in New York between 1885 and 1957, where family members established what would become thriving Hasidic communities in the city and its northern suburbs. (Other branches of the family landed in Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago and Canada, where they also built Hasidic communities.)

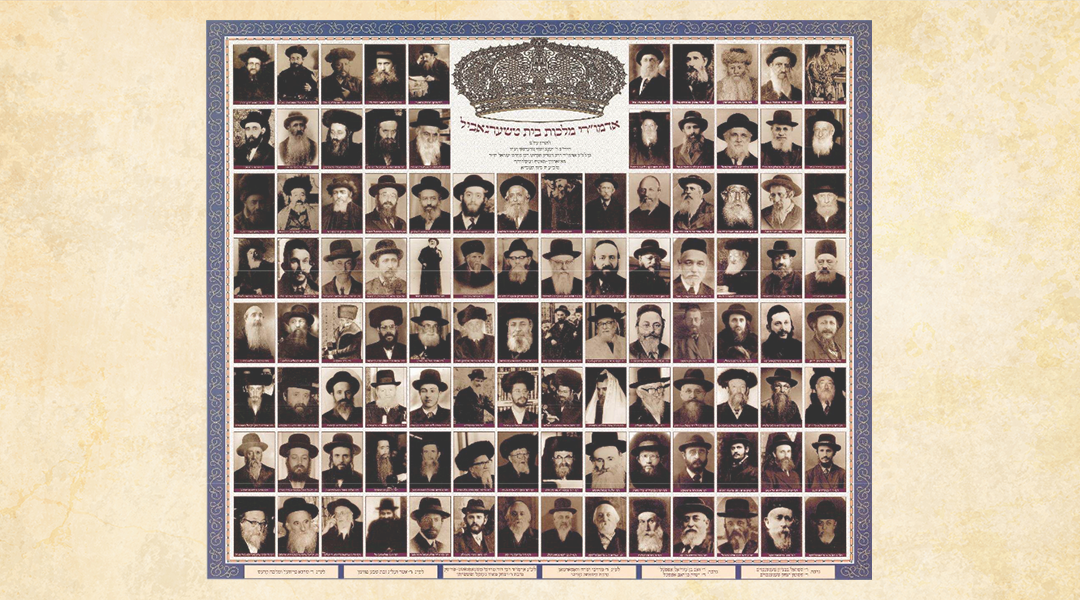

A poster made by Yitz Twersky in 2001 showing 104 Twersky rabbis. (Courtesy)

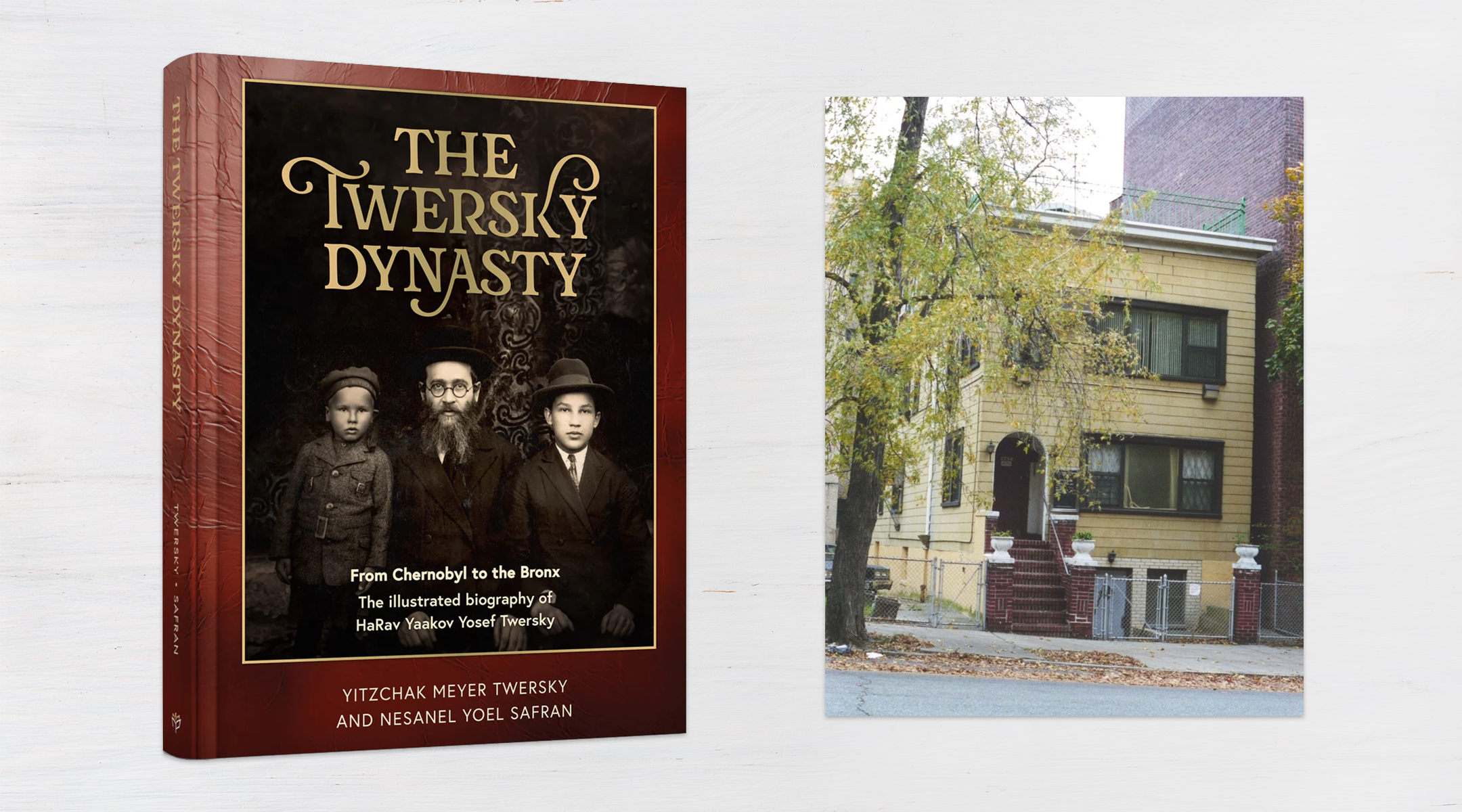

For Yitz Twersky, it’s not only pride in his ancestors’ role in shaping Hasidic Judaism that motivates his work: The author also sees his book as a way to honor his father, Jacob Twersky, who founded and ran a synagogue in the Bronx for more than 40 years. (The subtitle of the book, which is co-written by Nesanel Yoel Safran, is “From Chernobyl to the Bronx: The illustrated Biography of HaRav Yaakov Yosef Twersky.”) Jacob Twersky’s synagogue, Bronx Park East Chotiner Jewish Center, was located near the Bronx Zoo.

“In my small way, my father remains alive through all the years of Twersky projects done in his memory,” said Yitz Twersky, whose own bris took place at the synagogue. “They attempt to influence as many people as possible about our noble heritage.”

The family patriarch, Menachem Nachum Twersky, was orphaned as a young child before becoming a disciple of the Baal Shem Tov. According to “The Twersky Dynasty,” Menachem Nachum was cured of his illnesses and infirmities during a Torah reading by the Baal Shem Tov. He moved to Chernobyl in the early 1770s where he became a maggid, or preacher, and continued to live in poverty. One of his books, “Me’or Einayim,” was among the first Hasidic works ever printed. He died in 1797.

Menachem Nachum had two sons but only one of them, Mordechai, established a rabbinic dynasty. Known as the Chernobyler Maggid, he was the first to use the Twersky surname, the result of an 1804 edict issued by the czar mandating that Jews have last names. Mordechai Twersky had eight sons and, after he died, they all served as rabbis throughout Ukraine.

Some Twerskys came to the United States during early waves of immigration from Eastern Europe. “The Twerskys were among the first Hasidic rebbes in America,” said Samuel Heilman, a retired sociology professor at Queens College who has studied Orthodox Jewry. “That’s why they survived most of the deaths others suffered in the Soviet Union and in Europe.”

But many others did fall victim to the Holocaust, or narrowly escape it. Yitz Twersky’s book recounts the family’s life in Chernobyl then proceeds to tell the story of the dynasty’s spread to Khotin, a major Ukrainian town roughly 330 miles to the southwest. There, Yitz Twersky’s paternal grandfather, Mordechai Israel Twersky, served as the rebbe of Khotin from 1923 until his death in 1941. For a time, he led an idyllic existence there: His large home included a synagogue and he received hundreds of visitors — some of them non-Jews — from Ukraine, Romania and Poland who sought blessings and advice.

The Chernobyl shul in 1928. (P. Zholtovsky)

The book also includes a heart-breaking narrative of Mordechai Israel’s torture and death at the hands of the Nazis. He and his son were among 57 Jews rounded up and shot in July 1941 outside Khotin. The book quotes Rachel Katz, one of only two survivors of the massacre: “I heard a command to split into two lines, but before that order could be carried out, a shot rang out. Then, they began shooting with their machine guns. … We threw ourselves into the ditch, just like during a bombing.”

One of the revelations that most surprised Yitz Twersky was that his grandfather had tried to emigrate with his family to the United States before World War II. A New York lawyer was hired in 1939 by the Stoliner rebbe in Brooklyn to handle the family’s visa applications — Yitz uncovered documents at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, that revealed the ill-fated attempt to obtain visas.

“This record was the most emotional find,” Yitz said of his research process. “It posed the question as to what could have been if they immigrated in 1939, and how our lives would have been so different.”

Yitz then turns the book’s attention to his father, Jacob Twersky, whom he describes as an “unfathomably courageous teenager” who survived four years as a prisoner and who testified at the age of 18 before a Romanian government war crimes tribunal in June, 1945. Yaakov Yosef, as his father was known, traveled with his sister as stowaways on an ocean liner that left France and arrived at Ellis Island in 1946. For 10 years the American government unsuccessfully challenged their right to remain here.

“In America, my father had every excuse to justify renouncing his religious upbringing and leading a selfish existence,” Twersky writes in “The Twersky Dynasty” preface. “But he did just the opposite. He became a rav [rabbi], and for the next 60 years, he dedicated his life to serving others.”

Jacob Twersky was the spiritual leader of what was known as the Khotiner Shul in the Pelham Parkway section of the Bronx. He founded the synagogue — whose membership included Hasidic Holocaust survivors from Khotin who made their way to New York — in 1960 and led it until it closed shortly after his death in 2001.

Other Twerskys established outposts in areas with a more durable Jewish presence. For example, the Skver Hasidim, who now number 10,000, were among the Hasidic sects that established a base in Rockland County north of New York City in the 1950s. It happened under their then-rabbi, Yaakov Yosef Twersky. The Skvers eventually incorporated themselves as the village of New Square in 1961; the current Skverer rebbe is David Twersky.

In recent decades, the Twerskys have made their mark in secular professions as well the rabbinate. Take Aaron Twersky, 44, whose grandfather, Jacob I. Twersky, was known in Brooklyn’s Borough Park as the Chernobyler rebbe from the late 1930s until his passing in 1983. An ordained rabbi, Aaron, who lives in North Woodmere on Long Island, makes his living as a lawyer who specializes in white-collar criminal defense and complex commercial litigation.

“Being a Twersky is a responsibility,” he said, adding that his brother, Zvi, is the dean of a yeshiva in Israel. “You come from a very prominent [family with a] rich legacy. People sometimes expect more than they would from someone else, so you have to always accept that and let it encourage you.”

That sense of responsibility is shared by Connie Twerski, a 50-year-old Brooklyn-based consultant specializing in care of the disabled. She grew up in Milwaukee. “There was an incredible awareness of what came before us,” she said.

Left, the cover of “The Twersky Dynasty.” Right, the Khotiner Shul in the Pelham Parkway section of the Bronx, which was founded by the author’s father, Jacob Twersky, in 1960. (Seymour J. Perlin)

Twerski has serious yichus, or Jewish lineage, on both sides of her family: Her mother Feige was a Twersky before she married and a descendant of the Bobover rebbe, who died in the Holocaust. Her father, Michel, is the grand rabbi of the Hornosteipler Hasidim of Milwaukee and the twin brother of Aaron Twerski, an attorney who served as dean of Hofstra Law School and later Brooklyn Law School. Michel Twerski’s other brother was no slouch: Abraham Twerski was a Pittsburgh-area rabbi and psychiatrist who was an authority on addiction. Before he died in 2021 at age 90, Abraham Twerski wrote 80 books, including a series of self-help books with the cartoonist Charles M. Schulz.

“When I came to New York there was zero anonymity in being a Twerski,” Connie Twerski said. “The name comes with implications. You’ll never go anywhere without having somebody say, ‘Oh, you’re a Twerski. Are you related to …?’ There’s always some connection somewhere because between Europe and here, the family is related to everybody.”

The late David Twersky, who died in 2010 at age 60, was a Zionist activist, journalist and Mideast peace advocate who led the Forward’s Washington bureau for seven years starting in the mid-1980s.

Yitz Twersky said that the family has considered holding a global reunion, but “Madison Square Garden would be needed.” And he continues to encounter new Twerskys who are making a mark. Asked if he had ever met the formerly Orthodox actor Luzer Twersky, who played the Baal Shem Tov in the 2023 Ukrainian film “Dovbush,” Yitz responded, “Oh, yeah. We had him over for Shabbos.”

Before summer’s end, Yitz will meet with an Australian relative named Jonathan Tverski. A DNA test that Tverski submitted made it possible for Yitz to find thousands more Twerskys. Twersky and Tverski have corresponded for more than 30 years but this will be the first time they will meet face-to-face.

Yitz Twersky is not done searching for Twerskys or writing books about the family. He is planning a book on the traditions of observance and customs of the Twersky dynasty, and another that will examine press coverage of the grand rabbis. (“You think the paparazzi are bad today? In the 1800s the grand rabbis were constantly in the newspapers,” he said. “It was fodder for the paparazzi in those years.”)

“Since we went to print, I found so many items that I could have been included,” Twersky said. “There is no end. So many new things and records are coming out. I have no idea what’s coming next.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.