Some of the most iconic American folk singers of the 1960s and ’70s were Jewish: Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, “Mama Cass” Elliot.

But what if there had been an entire Jewish family of folk royalty, whose descendants became stars of their own respective eras?

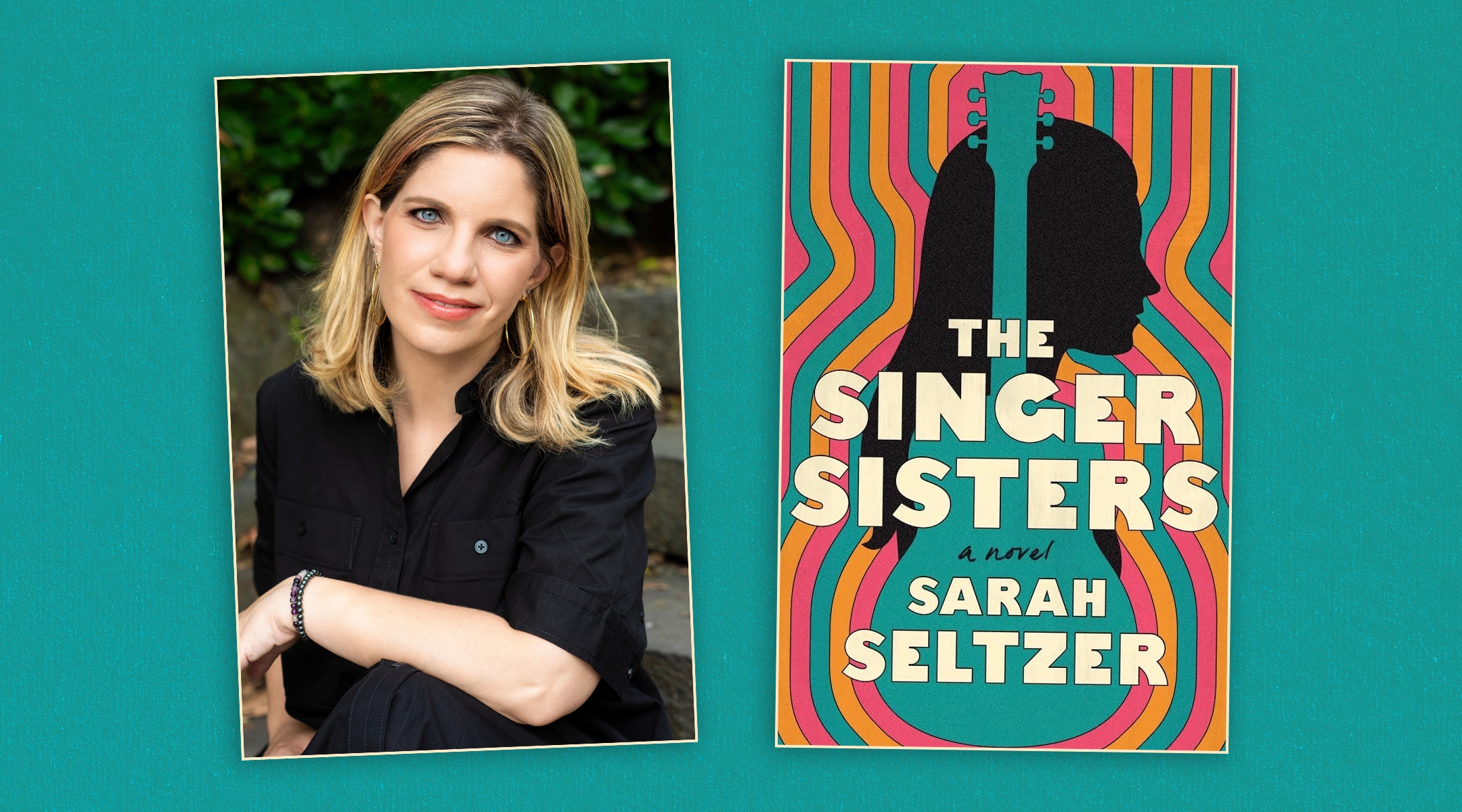

In her debut novel “The Singer Sisters,” which was published on Tuesday, writer and native New Yorker Sarah Seltzer dreams up this fantasy and fills it with rock music history, family drama and lots of Yiddishkeit.

Singer is a common Jewish surname, but the novel’s titular sisters are actually named Judie and Sylvia Zingerman. It’s the 1960s, and they hail from a Jewish family in Massachusetts but long to become musicians in Greenwich Village’s burgeoning folk scene. As they find their footing in this heady world — which, in the novel, is populated by real-life heroes such as Dylan as well as fictional singer-songwriters — Judie falls for a fellow Jewish singer named Dave Cantor (yes, another Jewish name joke), whose stage name is Dave Canticle.

With the help of their father, who owns a recording studio, Judie and Sylvia lay down an album and become stars — only to be derailed by the drama that ensues in the world of sex, drugs and rock-n-roll they inhabit. Eventually, Judie chooses to leave the industry to start a family with Dave, even as he continues to tour.

Later, Emma becomes one of the biggest stars of the late-1990s alternative rock scene in Los Angeles, in part by recording some of her mother’s unfinished songs. But their relationship is far from civil, and a longstanding family secret deepens the chasm between them. All roads lead back to New York, where tragedy — and Jewish deli food — brings them together.

We spoke with Seltzer, 41 — formerly the editor of New York Jewish Week sister site Kveller and currently executive editor of the Jewish feminist magazine Lilith — about Jewish rock royalty, the Village scene and how her Jewish husband, who works at Rolling Stone, helps her get in the creative zone.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited for clarity.

Has there ever been a Jewish rock and roll family like this — so openly, deeply Jewish, in a secular American kind of way — in a mainstream book or movie or show?

Not that I know of. There was a British novel that was maybe about like a Jewish rock family that I saw that came out at some point, but I never read it in part because I didn’t want to be influenced. But that’s the only one I can think of.

There were a lot of Jews in the folk scene, like Dylan, Paul Simon, Carole King, Cass Elliot — but if I was going to write a family drama, they had to be Jewish, and casually Jewish in the way that I am, joking about pastrami.

I just went to give a reading to my MFA program, which was not a particularly Jewish crowd, but my advisor was Jewish, and she said, “You know, you have the cadence of our people.”

So you didn’t sit down and say “All right, I have this family idea now. How do I make it Jewish?” It just came out of you naturally as you went?

From the very beginning, I knew they would be Jewish, and it just kind of came out of me. I didn’t plan that part out.

What were some inspirations, Jewish or not, for the family and the story?

There’s such a wide variety of inspiration. Part of it was just like growing up in the city in the ’90s. I read a lot of my parents’ magazines, and in the ’90s, there were a lot of stories, I’ve come to realize, about baby boomer musicians and their families, like Jakob Dylan [son of Bob]. And then also there was this big Vanity Fair article about the offspring of rockers from the ’60s that I found kind of fascinating. And there were articles about Joni Mitchell reuniting with her daughter — it was just in the air.

New York City is such a big presence in the book. It’s the promised land of sorts for Judie, and it’s where the characters feel most at home in the midst of touring and travel. Just how Jewish was the early scene around Dylan? I always pictured it as kind of WASPy.

It was both. Journalist David Browne has a book coming out in September about music in the Village, which I’ve been reading. There were a lot of Jewish people in that scene, and also a lot of WASPs too. Ramblin’ Jack Elliott was Jewish, and some other big figures. And then there was also Dylan’s girlfriend at the time, who was like an Italian red diaper baby [child of communists]. So I think there was just a big mix.

As I read the book, I wondered how the various members of the Cantor-Zingerman clan — who feel very deeply about the Vietnam War and other issues of their time — would have reacted to Oct. 7 and its aftermath. The Israel-Hamas war has opened up big rifts in a lot of multi-generational families, no matter how liberal some of them are. Do you think Oct. 7 would have them at odds with each other?

I do. I think they’d be arguing. So much of it is about the context you’re in, what people are around you, how are the people around you reacting. So I could see Emma going either way. I could see her going full-on for Palestine. Or, if she’s like around a bunch of non-Jewish leftists in upstate New York [where she ends up towards the end of the book], if she’s not in the city, she might react against that and feel left out or misunderstood because she’s not with her tribe in New York.

The characters are also constantly saying or doing something Jewish — do you have a favorite Jewish moment that you’re glad you got into the text?

I made deli food a funny recurring thing in the book. I think that was a little bit of a tribute to my grandma, who used to always order a platter of deli sandwiches from PJ Bernstein on the Upper East Side, near where she lived. For any occasion, it was like you have to have a big tray of sandwiches. My family usually does Barney Greengrass for our celebrations — it’s not deli, but it’s the same thing, right? So that just became kind of a little recurring joke that I threaded in.

You’re married to Rolling Stone editor Simon Vozick-Levinson, who is also Jewish. Did he contribute to any of the book’s content at all?

When you’re a teenager and you’re a young person, music becomes part of your identity and how you define yourself and what you do for fun. The older you get, the harder it is to keep up with music and to keep going to shows, and to maintain your fandom and feel that intensity. So marrying someone who’s in the music world meant that I was going to all these shows still, all the way through.

And I often find that going to a concert — I’m much lazier about going to shows than he is now that we have kids — I’ll be standing there and just get in the creative mindset. Going to all those shows that I went to that inspired the book were because of [Simon] — he’s like, “Let’s try to get into this show.” “There’s a Pete Seeger birthday concert, let’s go.”

Without giving too much away, Judie’s arc is an interesting commentary on trying to do creative work later in life, especially during and after early parenthood. And then Emma becomes famous at a young age. Do you feel like as a society we’re kind of moving past the goal of becoming successful by one’s early 20s?

This does come back to what we talk about a lot at Lilith. Rabbi Susan Schnur, who used to be on the staff before I worked here and is a legend in the office, calls it “species work.” Women often have to take a pause from whatever their ambitions are to do their species work, which is either taking care of their aging parents or kids, or the community. And so we’re often on a different timeline than skyrocketing to success in your 20s. So I think part of the message of the book is that there is no right time to do anything, and that part of what success should look like is meeting the challenges of life that unexpectedly come up, and trying to be a good person while also trying to find time to be creative and fulfill your dreams.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.