My family and I gathered this week at a memorial service for my stepfather, Sen. Joe Lieberman, who passed away earlier this year. Though we knew him as a loving parent, grandparent and husband, he was perhaps best known as the first Jewish candidate on a national ticket, a distinction he earned when selected by then Vice President Al Gore as a running mate in the 2000 election.

Twenty-four years later, we may have another Jewish candidate for vice president if Gov. Josh Shapiro is tapped. Other prominent candidates have Jewish spouses — including Vice President Kamala Harris, now the leading Democratic presidential contender, whose husband Doug Emhoff is Jewish; and Mark Kelly, reportedly also on Harris’ shortlist, whose wife is the Jewish former congresswoman Gabby Giffords. Of course we all recall, too, that Donald Trump’s daughter and her family are Jewish.

The presence of so many Jews on the national stage is naturally reigniting questions about the role of Jewish identity in politics that my stepfather answered loudly, in his own way.

My stepfather frequently described his ceiling-shattering moment in words offered to him at the time by Rev. Jesse Jackson: “Remember that, in America, when a barrier falls for one group, the doors of opportunity open wider for every single American.” I think he loved this framing because it matched how he saw his Jewishness: as a lever and fulcrum for moving the world to a better place. Jewishness was something very personal for him, yes, but it wasn’t private, and it wasn’t parochial. While he wore his Jewish practice with deep humility, he did so proudly and publicly, and he always believed that his faith connected him to others more than it separated him out.

Hadassah Lieberman, wife of Democratic vice presidential candidate Joseph Lieberman, is cheered by the crowd at the Democratic National Convention in the Staples Center in Los Angeles, California, Aug. 16, 2000. (Mike Nelson/AFP via Getty Images)

Jewishness in the public eye can take different forms. One type is virtually invisible, sometimes by design. Indeed, back in 2000, many Jews — whether out of fear or a different conception of the role of religion in the public square — wished my stepfather had gone this route. The kind of Jewishness that is in the “Personal Life” section of your Wikipedia page, accessible to the researcher but essentially unknown to the political observer. This is Jewishness by origin, by ethnicity, in biography, a private confession. It otherwise gets in the way of a dream of a more neutral, less religious society that treats all equally, regardless of our particular origin stories.

Another type of Jewishness is, in a way, partisan. It seeks out specific allies with one part of the political spectrum — sometimes the part imagined to be best for “Jewish interests” or for the pursuit of a more universal justice or some combination of the two. This type of Jewishness seeks to align itself with, to weld itself to, movements on one side of American political divides. This sort of Jewishness is highly visible, a deep substantive commitment that you can’t miss, even as it is also more narrow and political. This sort of Jewishness also often leads Jews to turn on their own — against those who didn’t get the partisan memo and who are, in the eyes of the beholder, misrepresenting and distorting our faith.

My stepfather walked a third path. He saw himself as part of a “group,” his beloved Jewish people, whose destiny in the arc of history fueled his energy and focus. He manifested his public observance of Shabbat to an audience broader than that of perhaps any Jew in history. There was nothing invisible about it.

But his Judaism was also never partisan, and not just in the political sense. He saw his own destiny, as an American, to leverage his Judaism to accomplish things for others, for the broader world in which he lived, for the country he so deeply loved and to which he gave a lifetime of service. Nothing less than that would do — did Jews not bear witness to and serve the God of the world, about whom they say three times a day: “God loves all and has compassion on all God’s creatures?”

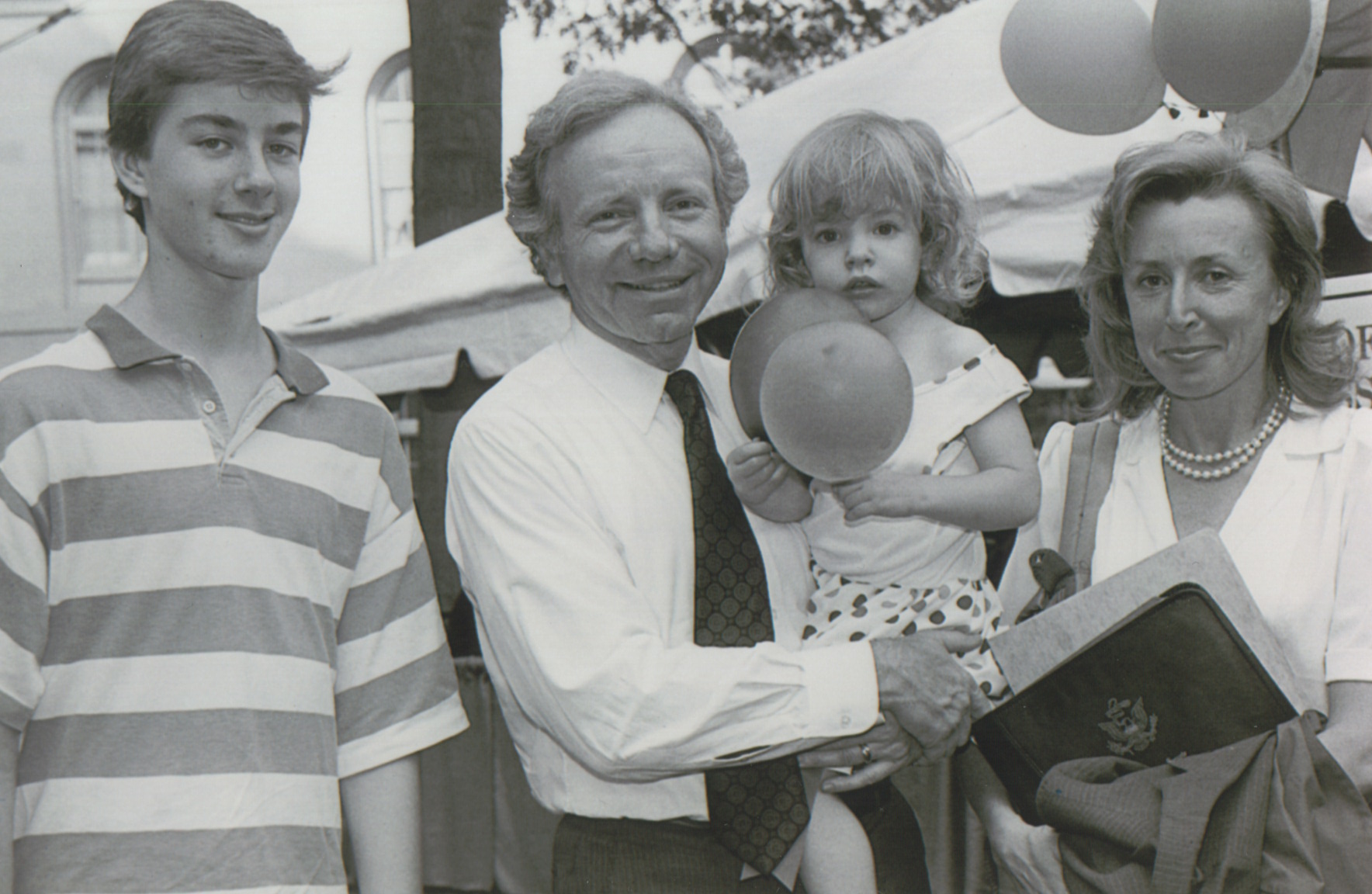

Connecticut Senator Joe Lieberman, his wife Hadassah, Hadassah’s son Ethan Tucker, and the Liebermans’ daughter Hana pose at a Capitol ice cream party in Washington, D.C., in an undated photo. (Getty Images)

More than two decades, later, Jews surely feel more vulnerable than they did back in 2000. The horrific events of Oct. 7, rising antisemitism at home and abroad, political instability — these could beckon Jews, and perhaps Jewish candidates and their family members, in the public sphere to invisible or partisan forms of Jewishness.

Joe Lieberman would have beckoned us to something different. Archimedes, when musing on the laws of physics, is said to have remarked: “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.” My stepfather would have asked us to consider: What if Judaism were that lever and that fulcrum? What if we are the ones uniquely positioned to move the world through a deeper embrace of who we are?

Jews — authentic bearers and owners of a Scripture viewed as sacred and foundational to an overwhelming majority of Americans and by billions of people worldwide. Jews — dogged political survivors, suspicious of untrammeled state power that threatens to slide into tyranny, able to connect profoundly with the notion of a birthright of freedom that should belong to all. Jews — a minority, often persecuted, able to understand the plight of the mistreated, the marginalized, the “strangers” in all the Egypts of history and to fight for them as an extension of our own self-preservation. Jews — exemplary beneficiaries of American opportunity, coming as immigrants and outsiders and ascending ladders of achievement and prosperity, poised to share a gospel of what America ought to be for everyone: a place where those of humble origin can shape the destiny of their society.

What type of Jewishness will be on display this election season? Where is Jewishness in America headed in the coming years? I hope it will be one that will live up to my stepfather’s example and make him proud.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.