The centuries-old tradition of Jewish women working so their husbands can be free to study Torah prepared one German Jewish immigrant in 19th-century New York to oversee something much more ambitious than her own household: She built and ran America’s first major organized crime syndicate.

That’s one of the fascinating takeaways from a just-published biography of Fredericka Mandelbaum, who spent several years as an impoverished street peddler before becoming a fence (buyer and seller of stolen goods) and mastermind of bank burglaries.

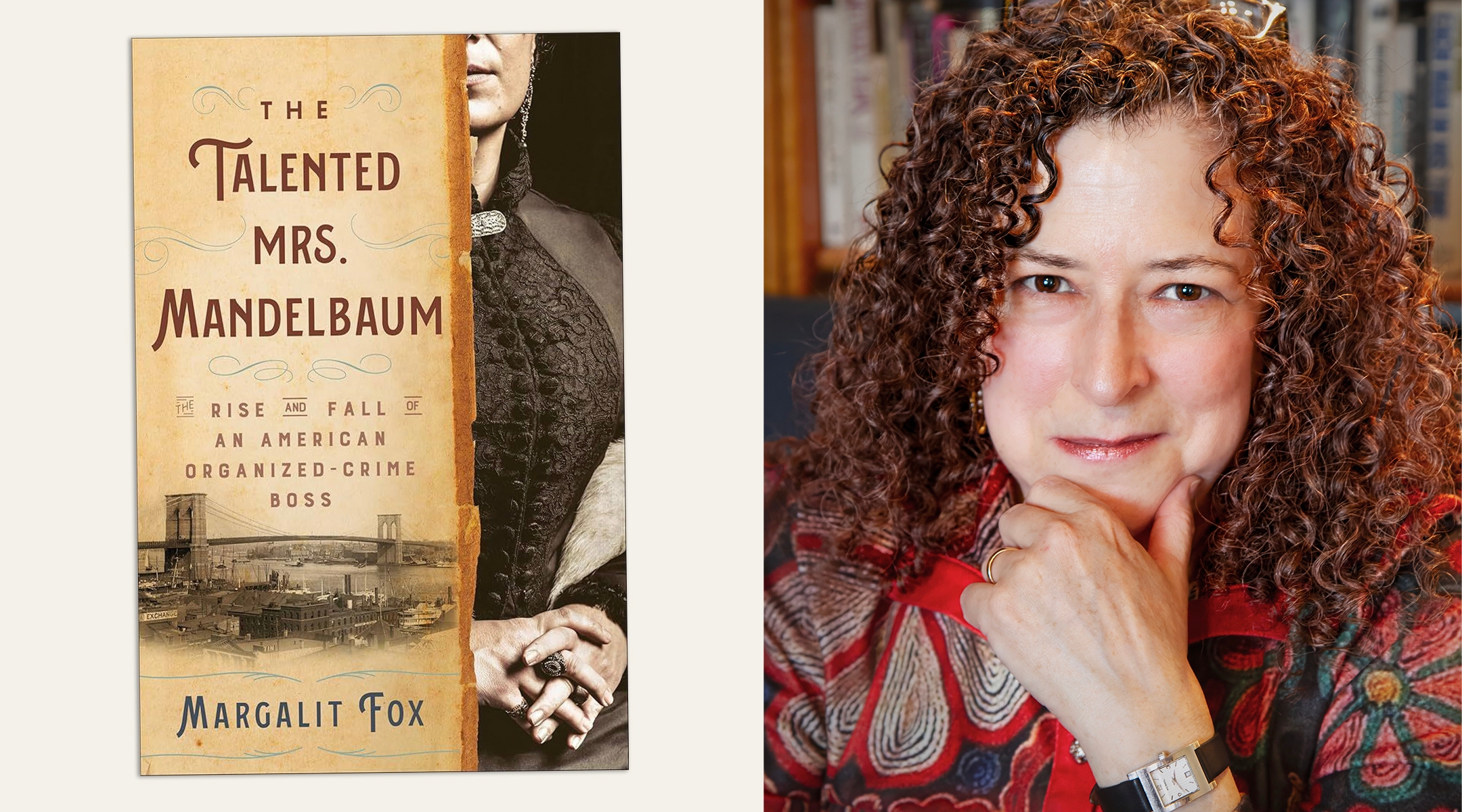

“A lot of the training that Mandelbaum and Jewish women of her time had taught them to run the economics of a family system,” Margalit Fox, author of the biography, “The Talented Mrs. Mandelbaum,” said in an interview.

“Fredericka Mandelbaum understood that she possessed the skills to run a family economy on a much larger scale. It so happened that it was a crime family.”

Born in Kassel, in what is now central Germany, in 1827, Mandelbaum was 25 when she immigrated to New York City, joining her husband who had arrived ahead of her. When he died in 1875, Mandelbaum was raising four children and was already regarded as the queen of the “sneak thieves.” Described in the press as homely and “almost masculine in appearance,” she was six feet tall, weighed between 250 and 300 pounds and wore dark silk gowns. Often, she was decked out in jewels that would be worth more than $1 million today.

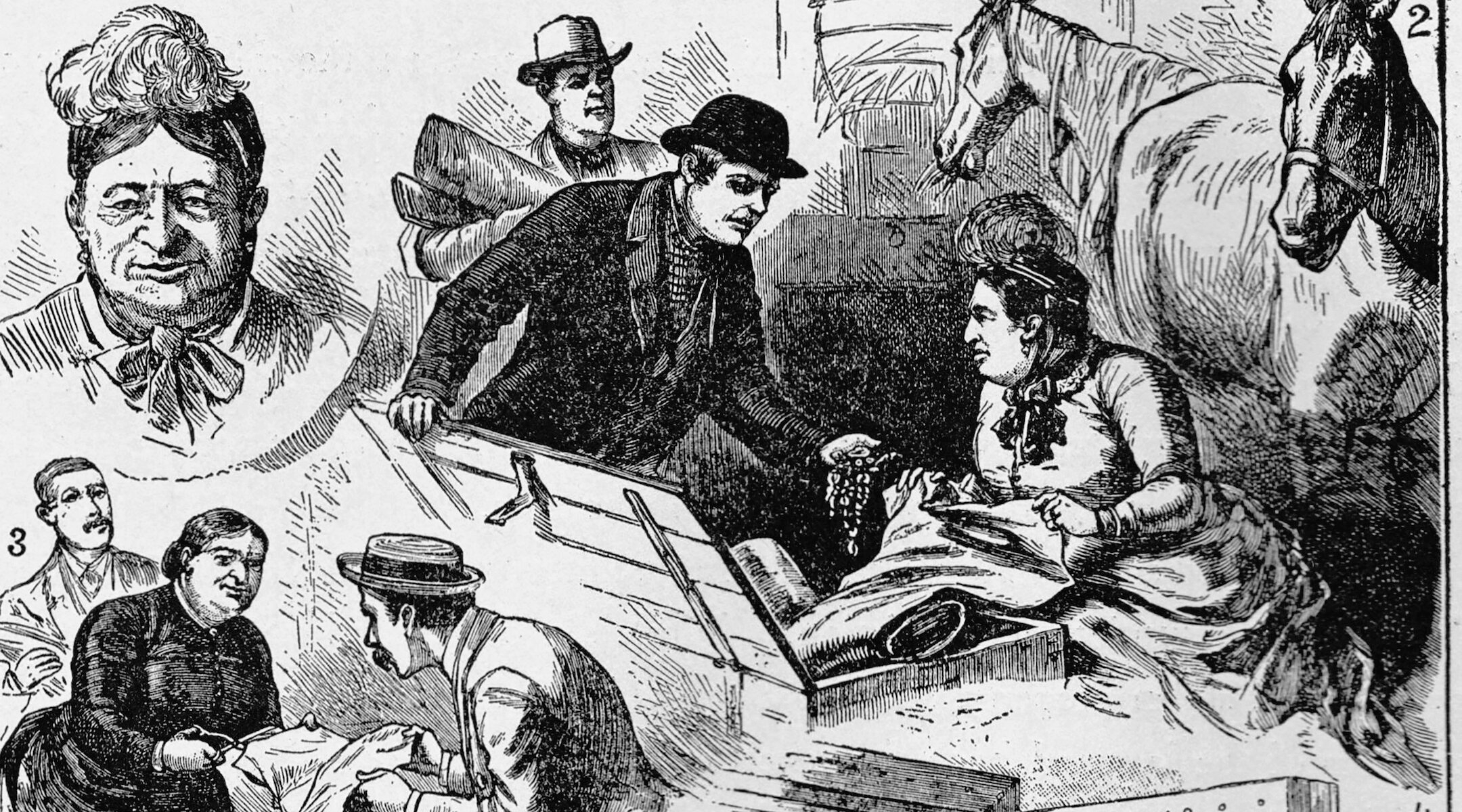

Contemporary illustrations depict the “German Jewess” with stereotypically antisemitic features.

Mandelbaum got so rich during her quarter-century criminal career that she could have lived anywhere in the city. But she opted to remain in a humble building in the Lower East Side neighborhood known as Kleindeutschland, or Little Germany. Until her downfall in late 1884, Mandelbaum used the building on Rivington and Clinton Streets as her home and workplace.

There was a haberdashery shop on the ground floor that served as a front for the fencing activity. The store sold deeply discounted fabric, ribbons, lace and trinkets. Her family lived in splendor on the upper floors. Fox describes the living quarters as a Versailles-like apartment with silken draperies, mahogany furniture and the finest crystal chandeliers.

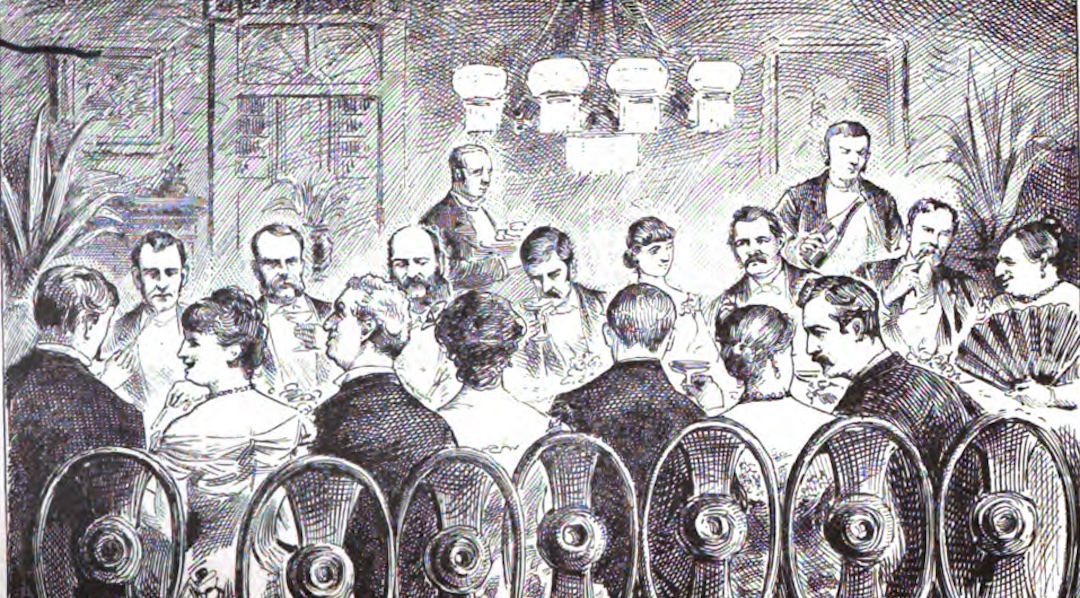

“She would routinely give the most lavish dinner parties that were as sought after as anything Mrs. Astor might give uptown,” the author said, referring to the Fifth Avenue arch-socialite Caroline Schermerhorn Astor.

The Lower East Side gatherings at the Mandelbaum home drew titans of industry as well as corrupt politicians, dirty cops and what Fox dubbed “the crème de la crème of criminality… the foremost shoplifters, house breakers, and jewel thieves.” They were all happy to break bread together at the table of Marm Mandelbaum, as she was known.

An illustration of a “typical” dinner party hosted by Marm Mandelbaum, shown at far right, from “Recollections of a New York Chief of Police” (1887) by George W. Walling. (Wikipedia)

Mandelbaum fenced everything from silks to securities. As a fence she “could estimate the value of a thief’s swag with a quick and ruthless scan,” according to a 2011 article in Smithsonian Magazine. Mandelbaum specialized in luxury goods procured by a network of thieves and then passed on to resale agents around the U.S., Mexico and Europe. Some of the theft was done by female pickpockets. Mandelbaum had a soft spot for female felons, including such shady ladies as Black Lena Kleinschmidt, Big Mary, Queen Liz, Little Annie and a woman known as Old Mother Hubbard.

The success of Mandelbaum’s criminal enterprise was very much a product of the times in which she lived. The Gilded Age saw a perfect storm of mass production, middle-class consumption, political graft and police corruption.

Many who have studied her life consider Mandelbaum a business savant. J. North Conway, who wrote the 2014 Mandelbaum biography “Queen of Thieves,” told The Forward, “If you were to do a flow chart of her enterprise, it would look like a very functioning business today.”

Gary Jenkins, a former Kansas City police detective who now hosts the Gangland Wire podcast, said fences thrive when buyers prefer to turn a blind eye to the source of cheap goods.

“In a way, fences operate in that world of approved crime,” said Jenkins. “Everybody wants that cheap stuff. Everybody wants something that fell off the truck.”

Fox spent 24 years at the New York Times, where she was best known as an obituary writer, sending off people both famous and charmingly obscure. Her previous books include “Conan Doyle for the Defense,” about how the creator of Sherlock Holmes helped solve a real-life case, and “The Confidence Men,” about a remarkable escape by two British prisoners of war during World War I. Film rights to the latter were acquired by Thunder Road Films, makers of the John Wick action movies.

Fox lives in Manhattan with her husband George Robinson, a former New York Jewish Week writer and critic. When looking for the subject of her next book, Fox has a ritual that involves searching through her private library, which is how she stumbled upon Fredericka Mandelbaum. A thick encyclopedia of true crime opened at random to an entry on the Grand Street School, where legend had it that Mandelbaum taught students how to become successful thieves. That turned out to be an urban legend, but Fox had found the subject of her next book.

Margalit Fox found the subject of her new book while flipping pages of a true crime encyclopedia. (Random House; Ivan Farkas)

“To my great pleasure, in addition to being a story about lost women’s history, this turned out not to be a story about violence, but a business story,” said Fox. “She was a brilliantly gifted entrepreneur. What she did [was take] the ad hoc, scattershot, fairly unremunerative enterprise of property crime and systematize it, regulate it and hire the best people in the country to do it for her. She turned it into a well-oiled going concern.”

Perhaps Fredericka Mandelbaum thought “Thou Shall Not Steal” didn’t pertain to her. She nevertheless was a committed Jew. Fox describes her as a “generous member” of Congregation Rodeph Sholom in its early years when the synagogue was located on the Lower East Side. (The synagogue moved to its current location on the Upper West Side in 1930; the Clinton Street building is now home to Congregation Chasam Sopher.)

In late 1884, the law caught up to Mandelbaum, and she jumped bail and fled to Canada, which had no extradition treaty with the U.S. at the time. She ended up in Hamilton, Ontario with her son and an associate. She died, still a fugitive, 10 years later, and was buried in a plot at Rodeph Sholom’s Union Field Cemetery in the Cypress Hills section of Queens.

There is one aspect of Mandelbaum’s brand of organized crime that Fox respects: It was almost entirely nonviolent.

“She wasn’t having people whacked,” Fox noted. “She wasn’t having her boys break anyone’s kneecaps with baseball bats. That came much later in the early 20th century” during the heyday of Jewish gangsters in the 1920s and ’30s.

And yet, Fox resists the temptation to treat Mrs. Mandelbaum, however talented, as a role model.

“She made her livelihood by having her minions steal other people’s property,” said Fox. “That cannot be overlooked.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.