On Monday evening, hundreds of Hasidic men crowded into a squat building at a cemetery in Queens, sitting shoulder-to-shoulder at cafeteria-style tables, studying Jewish texts and preparing to visit the gravesite of their late leader.

The men were some of the 50,000 people who this week visited the gravesite of Chabad-Lubavitch Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, known as the Rebbe, to mark the Jewish anniversary of his death, which fell on Monday night and Tuesday. Some had met the Rebbe when he held court at Chabad’s home base of Crown Heights, Brooklyn.

But for those born after his passing 30 years ago, a visit to the Ohel, as his gravesite is known, is the closest they can physically be to the last leader of their global movement.

Large tents accommodate the crowds gathered at a Queens, New York cemetery to mark the 30th anniversary of the death of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, July 8, 2024. (Luke Tress)

“People of my generation, we have a yearning,” said Levi Shmotkin, 26, who was one of the visitors to the Old Montefiore Cemetery on Schneerson’s yahrzeit. “Instead of me studying the Rebbe’s interaction with another teenager, I wish I could be that teenager.”

Like some other Chabadniks under 30, Shmotkin has immersed himself in Schneerson’s teachings, which are organized in compendia of letters he wrote and talks he gave in Crown Heights. Shmotkin felt drawn to the letters Schneerson exchanged with those seeking his counseling. He has now published his own book on the correspondence, called “Letters for Life.”

“It is only after the teacher leaves and the students are left alone that the students can then take apart and really understand what the teacher said,” Shmotkin said while visiting the site. He spent five years organizing Schneerson’s 13,000 archived letters thematically, with a focus on emotional wellness.

Visitors studied and prayed before paying homage at the resting place of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, on the 30th anniversary of his passing, in Queens, July 8, 2024. (Luke Tress)

“We didn’t have that all-encompassing experience of being in the Rebbe’s presence. That gives us the ability to dissect what he’s saying and make a comprehensive picture of it,” Shmotkin said.

Chabad has not had a leader after Schneerson — the seventh rebbe of the movement, which was founded in the 18th century in the Russian Empire. In the years following his passing, a contingent of Hasidim have professed that he is the messiah, creating tensions in the movement.

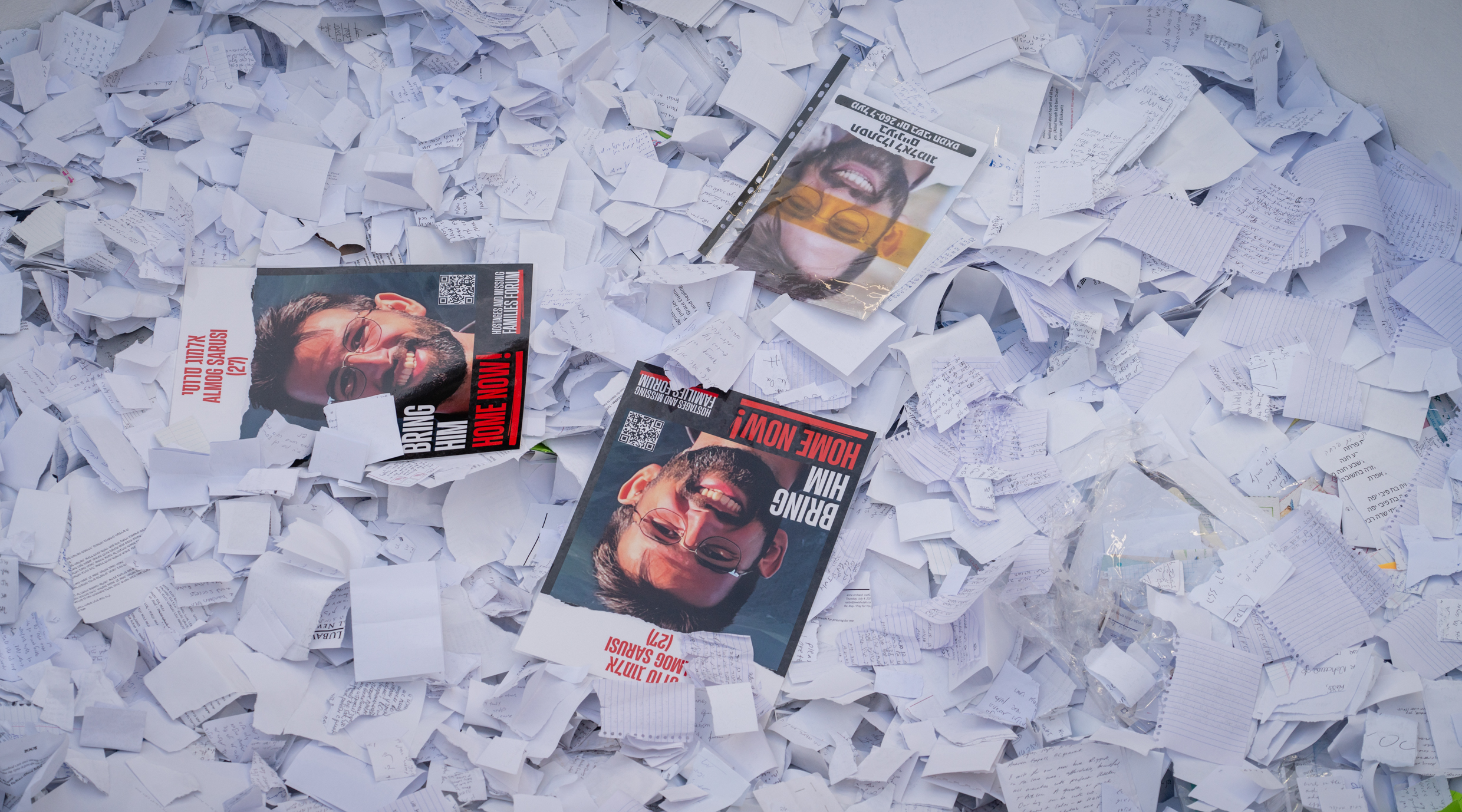

Those tensions were absent on Monday night, when visitors packed into Schneerson’s walled gravesite, where he is buried alongside his father-in-law and predecessor, Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn. Men and women filed into the enclosure and, per Orthodox practice, stood with a barrier between them. Nearly all said prayers or left notes on top of the graves. One man left several pictures of Israeli hostages held in Gaza and said a prayer wishing for their safe return.

Photos of Israeli hostages in Gaza on top of prayers placed on the resting place of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, July 8, 2024. (Luke Tress)

A long line wound outside the tomb into the street outside, where attendees lit candles in the hot summer night.

Lighting candles outside the resting place of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, in Queens, July 8, 2024. (Luke Tress)

Over the decades, the Ohel has become a pilgrimage site for celebrities and politicians as well as Chabad Hasidim. At 1 a.m. on Tuesday morning, New York City Mayor Eric Adams became one of the thousands who visited the grave.

“His influence shaped our city for the better by reminding us even small deeds can change the world,” Adams posted on X. “Let’s honor his worldwide legacy by increasing our acts of kindness.”

Visitors traveled to Queens from far beyond the New York-area to mark the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s 30th yahrzeit, or anniversary of his death, July 8, 2024. (Luke Tress)

Shneur Itzinger, 27, a Chabad emissary in the small Cleveland-area town of Chagrin Falls, Ohio, said that he feels that influence when reading Schneerson’s words. Itzinger, who traveled to New York for the yahrzeit, said he finds inspiration in Schneerson’s encouragement of outreach to the Jewish world — a centerpiece of Chabad’s work. Under Schneerson’s watch, the movement built some 5,000 Chabad centers in 100 countries — often serving as the only Jewish game in town for travelers in far-flung countries, or drawing Jews who may not themselves be Orthodox but appreciate Chabad’s come-as-you-are philosophy.

Itzinger feels that the passage of time has clarified the Rebbe’s teachings.

“Obviously, there is something to be said for being able to have a personal conversation, one on one, or even just seeing him physically, but I don’t think that in the essence of it there’s anything missing,” he said. The teachings “are not just still there, they’re a lot more accessible today than they were ever.”

Worshipers offer prayers the gravesite of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, in Queens, July 8, 2024. (Luke Tress)

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.