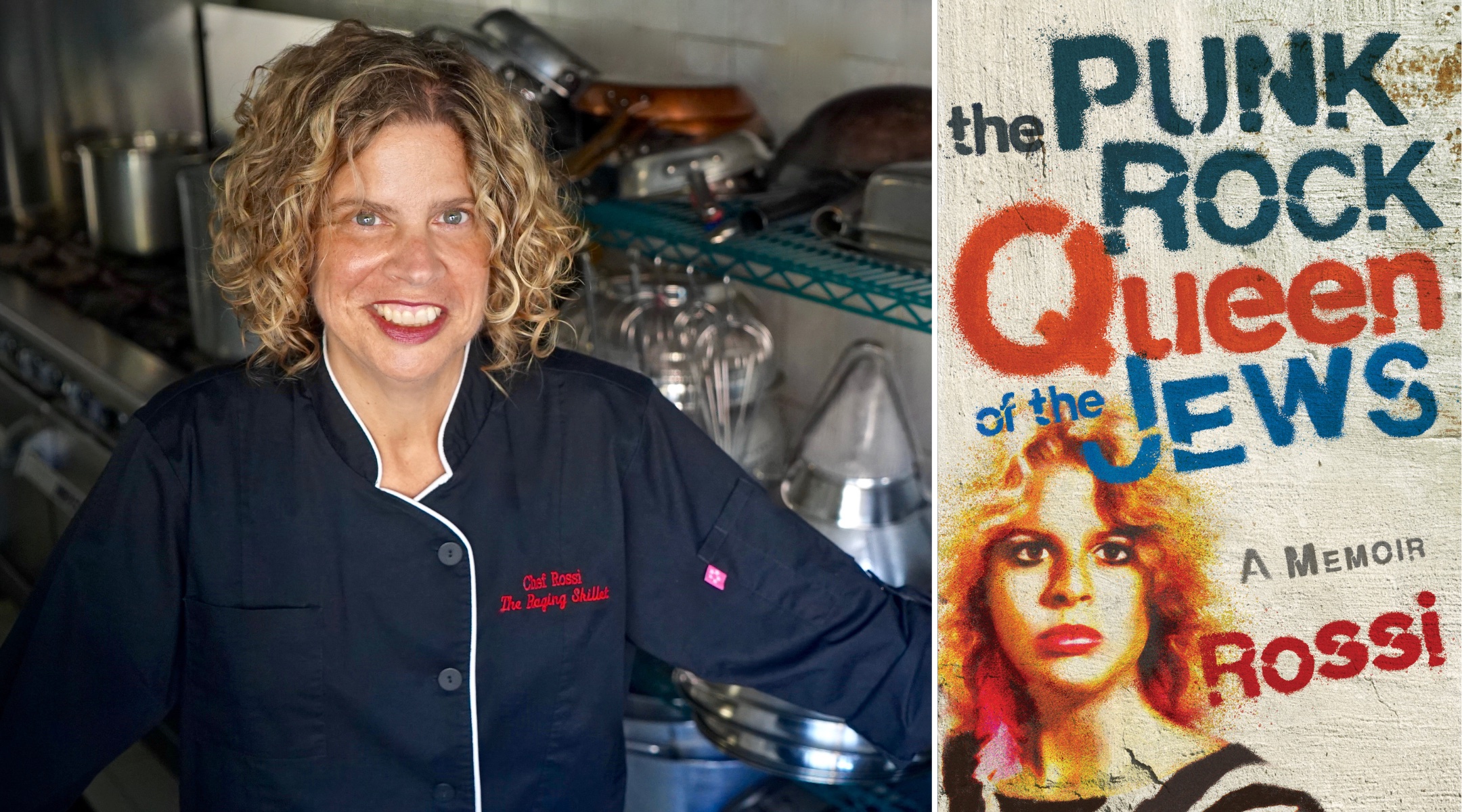

Chef Rossi’s day job is running a catering company, The Raging Skillet, where she creates unique recipes to match her clients’ needs. Rossi calls herself the “anti-caterer.” She is known for being one of New York’s first caterers to work a same-sex wedding, and gained attention when she catered the afterparty for “The Vagina Monologues,” with anatomically correct fruit platters.

Rossi goes by the mononym, like Beyoncé, or Shakira — it’s a nickname she picked up in middle school, she says. She added “Chef” decades ago, she said, because “the world wants you to have two names.”

But before she was Chef Rossi, she was Slovah Davida Shana bas Hannah Rachel Ross, growing up in what she described as a “white trash Orthodox family” on the Jersey shore in the 1970s. After running away from home at 16, partying and getting into all sorts of trouble, her parents shipped her off to the big city — that is, Crown Heights in Brooklyn — to live with a Chabad rabbi who had a program for reforming wayward girls.

Rossi told the story of her rise through New York’s culinary scene in the 1980s in her first memoir, also called “The Raging Skillet,” which came out in 2015.

Her second memoir is more of a prequel than a follow-up. In “The Punk Rock Queen of the Jews,” released earlier this year, Rossi digs into everything that came before: specifically, the two years she lived in Crown Heights as a teenager. The book narrates what she describes as the misogyny, assault and trauma she experienced there. These experiences would shape the rest of her life, inspiring her to become a chef and come out as lesbian.

“It is the most unusual ‘How I Came to New York’ story, which I would tell when I was a starving artist in the 1980s and wanted a free drink,” Rossi told the New York Jewish Week. “Most people would say ‘I came for love;’ ‘I came for school;’ or ‘I came for a job,’ and I would say ‘I was sent to live with a Hasidic rabbi who specializes in turning around wayward Jewish girls.’ I would always get the free drink.”

The New York Jewish Week spoke to Rossi about her new book, her journey as a Jew and why she’s sharing it all now.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to write more of your backstory for your second memoir?

I could almost write a book on what’s happened to me since I wrote “The Raging Skillet.” It was adapted for the stage and it became a play and traveled around the country. We had our first off-Broadway reading starring Judy Gold. But I would say my first book was G-rated or PG-rated.This book is like R-rated. It was a story that I never really told and I never really wanted to tell. I certainly couldn’t have told it while my parents were alive — it would have killed them.

I always meant to tell the story of what really happened when I went to Crown Heights, but I had my mother’s voice in my head the whole time: “Don’t do it if it’s bad for the Jews, don’t say it if it’s bad to the Jews. Don’t air the dirty laundry in public.”

Then my mother passed away in 1992. After always being the black sheep of the family, I wound up being the one that my father wanted to care for him in his last years. In the last month that my father was alive, in March of 2016, he was in hospice care. I rented a little motel room right next to where he was staying in the nursing home. I would be with him all day and I would come back at night and I couldn’t sleep, so I started typing away. Out came 300 pages of what would later on become this book. I just decided that it was time to finally tell the story. Enough years had gone by that I was able to have enough forgiveness and enough love in my heart that I knew I could tell the story of what happened and not have it be something that someone would read and become antisemitic — that’s what I was worried about.

To whom did you extend that forgiveness – did that include some of those who hurt you when you were sent away?

I did meet some very, very bad people amongst the Hasidim in Crown Heights. But I also met some beautiful, wonderful people.

The trick was to write the story, not while I was still hurt and angry, but when I had some distance and forgiveness and certainly there were things that helped make that happen. Caring for my father helped me forgive him and helped me heal myself. I joined CBST [Congregation Beit Simchat Torah] — just being able to go to shul with a female, gay rabbi, and see women holding hands with women and men holding hands with men and all of that — helped me come around to finding my own kind of Jewish, in which I accepted that women could be every bit as powerful as men and that love is love and everything I needed to hear. All of that was very healing.

So, in the end, I decided that I had to tell my story. It was just something I carried around like a giant rock, so I had to let it out. But I also hoped that maybe young people — especially young Jewish people who are gay who are trapped in these worlds that don’t accept them — might feel inspired and braver after they read it.

What has it been like since you published the book — were your fears of writing something “bad for the Jews” warranted?

I had a fantastic book launch at this giant bookstore in Brooklyn called the Powerhouse Arena, which really feels like an arena — people were pouring over from the balcony, all the chairs were taken. It was just as good a book launch as one could be. It was also very touching, because as I looked around the audience, I saw new friends of mine, I saw people I didn’t know who had read about me. But then I also saw my friend from when I was 12 years old in the fifth row, friends of mine from theater when I was 15 years old in the balcony, just sort of people from all walks of life were scattered all over this place.

Everyone was having the time of their life. The room felt like it was floating. There was so much joy. Everyone was laughing. I also did a launch in New Jersey near my hometown and a million people that I’d known from high school and beyond came out and that was really lovely and validating. The nicest thing has been the emails and the messages I’ve been getting, from people, especially daughters, who are making their entire families read the book.

I have had a lot of women contact me who were trapped in the Hasidic community and who were lesbian that were just living a double life and afraid to come out as who they are just really feel loved and validated by my story, and that just makes me so happy.

What is your relationship with Judaism now?

My friends tell me I’m the most Jewish person they know, which I take as a huge compliment. I feel deeply Jewish in this really profound way. I was raised what I would call lowly Orthodox. We kept kosher, we went to shul on Shabbos, we kept the meat and dairy dishes separate, the Passover dishes separate — the whole shebang. But my mother was the queen of like coming up with little little twists and turns that would make life a little easier.

As an example, she really could not stand cleaning the house for Passover. So, my father had a Ford pickup truck and he bought this hermit shell kind of camper that wedged just on top of it. So one day my mother is cleaning the house for Passover, and just moaning and groaning and complaining to all of her dead relatives. She looks at the camper on the cinderblocks and this giant light bulb goes off: Why clean the house if all she has to do is clean this little camper? She cleans the camper and tells my father to put it on the truck. She plops her children in the truck and she says “drive and don’t come back until the end of Passover.” We wind up in these horrifying little truckstops off I-95 in the 1970s, having our Passover Seder in the parking lot while 18 wheelers are driving by. People just think we’re from Mars. It makes for a great life story, of course, but it’s a little quirky.

I always felt just really deeply, deeply Jewish. I don’t keep kosher anymore and I’m not a kosher caterer. But there’s still certain things I just cannot do. I’m famous for a million things I make with bacon and pulled pork and barbecue and all of those things, but I have never put a piece of pork in my mouth in my entire life. I have all of these tasters lined up and they’ll tell me what it needs but I just can’t put it in my own mouth. I feel my mother would be mad at me.

I’ve gotten louder about being Jewish since Oct. 7. I feel so much antisemitism — a lot of people are telling you they’re afraid to wear their Jewish star or they’re just scared for their children. The more I hear that, the louder I get. I’m at the point now where I almost tell someone I’m Jewish before I even tell them my name.

Bonus question: What else do you want people to know about your story?

I did feel and I still feel some connection, like love almost, for the [Chabad] Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson. As this punk rocker who was kidnapped by her parents and forced to live with the Hasids, who had these horrifying experiences, you wouldn’t think I would have those feelings for him. But when I met him, I just felt that he saw me and no one else did. I just felt him in my heart and thinking about him now, I still do. It’s easy to understand why so many love him. He really had so much magnitude and so much power that even me, this renegade pink-haired punk rock freak who was very unhappy to be there, even I noticed.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.