On one of her final Shabbat mornings as senior rabbi at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, New York City’s pioneering LGBTQ-oriented synagogue, Sharon Kleinbaum was presented by her junior clergy with a plaque that etched into wood one of her well-known nuggets of wisdom.

“The Kleinbaum Shmear Rule,” as it is known, goes like this: “When taking a bagel at the oneg, do not pause to shmear the bagel while still in line, lest those waiting be made to wait longer, increasing their hunger and their ire on a holy day. Rather, take the shmear and put it on one side of the plate, and shmear the bagel once seated, for the sake of the ways of peace.”

It’s an excellent guiding principle, to be sure, but it hardly encapsulates Kleinbaum’s 32-year career as the spiritual leader of the world’s first queer synagogue. Since assuming the helm of Beit Simchat Torah in 1992, Kleinbaum has led the community through both crises and milestones, from the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s to the legalization of gay marriage in 2015.

When Kleinbaum, 64, started at CBST, the synagogue had an operating budget of around $40,000 — today that number sits closer to $5 million. Under her guidance, the congregation has grown to a membership that’s more than 1,200 people of various sexual orientations and religious denominations.

She also spearheaded the establishment of a music program, children’s programming, a rabbinical internship program and immigration clinic. Ahead of her retirement at the end of July, a June 3 gala at The Appel Room honored Kleinbaum’s legacy, with high-profile speakers that included former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and video remarks from President Joe Biden and Senator Chuck Schumer.

“I feel deeply privileged,” Kleinbaum told the New York Jewish Week from her office via Zoom. “I am grateful every day that I was able to contribute something, that I was able to be of service, that I was able to be useful. That’s the best we can hope for and I feel like that’s why God put me on this planet.”

Hillary Clinton gave remarks at a gala honoring Rabbi Kleinbaum on June 3, 2024. (Sara Krulwich)

When Kleinbaum took the helm as CBST’s first full-time staff person and rabbi, her path for leadership was largely uncharted. Formed two decades earlier in 1973 as the country’s first LGBTQ synagogue, the congregation held Friday night services in a church in Chelsea and notices were placed in the Village Voice to advertise the services. According to the CBST website, the first Shabbat drew “barely a minyan,” the 10-person prayer quorum required for communal prayers..

“Not a single rabbi in the world — not a single synagogue, not a single Jewish organization, no single Jewish civil rights organization — stood for the full equality of LGBT people,” Kleinbaum said of CBST’s origins. “When it started in 1973, it was such a radical act — although they just wanted to have a Shabbat service where they could be deeply Jewish and openly gay.”

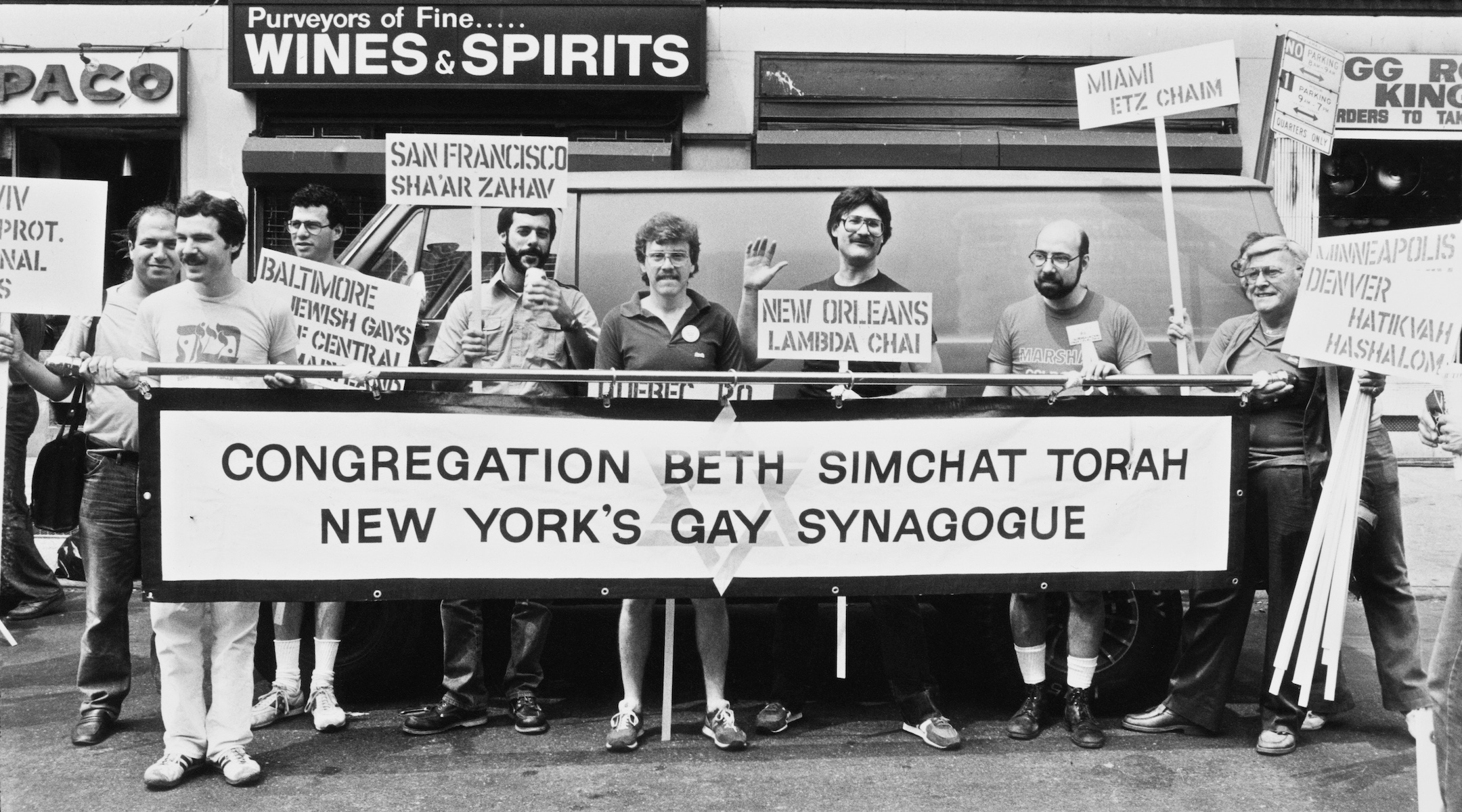

Members of Congregation Beth Simchat Torah and queer Jews from around the country join Gay Pride Day in New York City, June 27, 1982. (Barbara Alper/Getty Images)

By the time Kleinbaum, who was ordained at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in 1990, joined the congregation, the community was facing a crisis: The AIDS epidemic was sweeping through New York City, decimating the gay community and many of the synagogue’s members.

“It just became too much to carry the load of illness and death and grief and suffering, so the synagogue decided to hire a rabbi,” Kleinbaum said. “My first month there, I did four funerals, including the president of the synagogue.”

At age 33, “I was burying my own generation,” she said.

Kleinbaum estimated that in the ’80s and ’90s, CBST, known as “the gay synagogue,” lost about 40% of its members to AIDS. The community was also battling homophobia within Jewish spaces as well as the world at large.

“During the AIDS period, I understood that I needed to build a community that would have the strength to support each other through the suffering,” she said. “We couldn’t shake a magic wand and get rid of AIDS, but what we could do is make sure nobody was alone, and we could ensure that Shabbos was a place of joy and nourishment.”

Kleinbaum, far right, leads a Torah service in the 1990s. (Courtesy Sharon Kleinbaum)

Kleinbaum describes how, in the first few years of her tenure, she and “all the wonderful lay leadership” fought against the physical and emotional devastation caused by AIDS and homophobia by building a community that met the social, intellectual and spiritual needs of its members, where it was possible to be both “deeply Jewish and openly gay.”

One way she did this was by investing in creating a serious music program for Shabbat mornings, which began when she hired music director Joyce Rosenzweig to found the congregation’s community chorus in 1994.

“Music has been, for many years, one of the things that sets apart CBST,” Rosenzweig said. “People are looking for a shul where music moves them and uplifts them and takes them from the drudgery of the rest of their week and brings them to a higher place.”

Kleinbaum and music director Joyce Rosenzweig, right, started working together in 1994 to establish a music program at CBST. (Sara Krulwich)

Kleinbaum also established a rabbinical internship in 1996 to train another generation of rabbis to “meet the needs of people with AIDS and LBGTQ people,” she said. The program now has about 50 alumni who remain in touch and come together for guidance, support and text study.

“The ripple effect is really tremendous,” said Rabbi Ayelet Cohen, who was an intern at CBST from 2000-2002 and is now the dean of the rabbinical school at the Jewish Theological Ceremony. “[Kleinbaum] was an incredible model of how to be an activist firmly planted in the Jewish community and in Jewish tradition, of how to develop our own rabbinic voice and how to effect change in a way that is meaningful and grounded.”

She added: “At CBST, we learned to do the work to make it possible and available to be deeply Jewish and openly gay in more and more segments of the Jewish world, and because we were trained so holistically, we felt prepared to enter different aspects of the rabbinate and really thrive there.”

Perhaps one of Kleinbaum’s greatest accomplishments was securing a permanent space for the congregation at 130 West 30th St. in 2016. She told the New York Jewish Week that she began to plan a move in 1995, and spent the next decade and a half conducting feasibility studies and raising funds for a permanent space. CBST purchased its space inside the landmarked Cass Gilbert building in 2011 and began renovations in 2013.

In many ways, CBST is in a period of stability that was all but impossible to imagine in its early days. With medical progress meaning that AIDS was no longer a death sentence, the legalization of same-sex marriage and more options for gay couples to raise children, gay life in America has transformed. In the Jewish world, where it once went without saying that “people had to choose be Jewish or be gay or hide one of those,” as Kleinbaum recalls it, more and more synagogues embrace their LGBTQ members.

Kleinbaum has been at the center of these strides — both in the Jewish world and the secular one. She worked with the Conservative, Reform and Reconstructionist movements to update their practices to embrace gay members, celebrate lifecycle events and ordain LGBTQ clergy. As a representative of queer clergy, she has served on the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom and the New York City Human Rights Commission. She was a founding member of the New York Jewish Agenda and has been a longtime member of the New York City mayors’ interfaith councils.

She and her wife of six years, Randi Weingarten — president of the American Federation of Teachers — often team up to advocate for the causes they share.

Rosenzweig said Kleinbaum has been such an effective voice and changemaker because “she comes from a place of love and a place of generosity of spirit and of openness” and that “she brings strength to everyone around her, because of her solidity in her convictions.”

And yet, creating space and tolerance for LGBTQ Jews among the mainstream community was not always Kleinbaum’s primary motivation. Rather, it was “creating something that is spiritually and Jewishly meaningful and authentic and rich and deep,” she said, where “God really is present” and prayer is taken seriously.

“I don’t care whether people are accepted or not in other synagogues, I care that we create a Judaism that’s actually worth saving, that’s actually worth handing down,” Kleinbaum said. “I totally reject the kind of pediatric, insipid Judaism that exists in many synagogues in the non-Orthodox world.”

As she departs her pulpit, Kleinbaum acknowledges that her work is not yet complete. Last year 2023 saw a record number of anti-LGBT laws both proposed and passed around the country, including legislation censoring school curriculums and banning gender-affirming care.

“LGBT rights are absolutely under attack and religion is often the source for it,” Kleinbaum said. “We’re in a period now of tremendous anti-LGBT energy — many anti-LGBT legislations are being proposed, some passing and this particular Supreme Court is clear that should the right decision with the right structure come before it, we can expect to see the elimination of what we know of as gay rights here in this country.”

Kleinbaum and her wife Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers. (Laurie Rhodes)

Another communal crisis is, of course, the Israel-Hamas war, which has caused great turmoil in the Jewish and queer communities.

As someone who is dedicated to an “absolute commitment to the full humanity of Palestinians, and the full humanity of Jews,” Kleinbaum has trained her energy on promoting peaceful solutions. She’s brought speakers from Standing Together, Combatants for Peace and Parents Circle Family Forum — all organizations that advocate for a shared future between Israelis and Palestinians — to speak at the synagogue.

“I want to expose [CBST members] to those who believe deeply and are fighting for a different future that rejects the fascism of Netanyahu, that rejects the racism of the settlers and that rejects the violence,” said Kleinbaum, who considers herself a progressive Zionist. “I stand with those Palestinians and those Jews who are working for a shared future that deeply respects the full humanity, the full liberation, the full security and justice for all of them.”

“We’ve lost a few members this year — some who think that I’m too sympathetic to the Palestinians and some who think I’m too sympathetic to Israel,” she added. “I’ve been called the genocide rabbi and I’ve been called an anti-Zionist.”

Kleinbaum — who said previously she’s stepping down to “make room for a younger generation of leadership” — acknowledges that she’s leaving with unfinished business. “But that’s life,” she said. “No one can do everything, but everyone can do something. You just have to keep creating holiness, creating beauty, fighting injustice, doing what you can.”

Jason Klein, the former president of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association, will take over the role as senior rabbi at CBST on Aug. 1. The synagogue has established the Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum and Randi Weingarten Fund for Social Justice in honor of Kleinbaum’s career. It has raised $1.3 million of its initial $1.5 million goal. The money will be used to continue the rabbi’s mission to pursue social justice and LGBTQ activism.

“What we have created here is a very thriving, growing synagogue in a time when many non-Orthodox synagogues are not,” Kleinbaum said. “I wanted to change Judaism, and I feel like we changed it radically.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.