During his Depression-era run as one of the country’s most popular radio personalities, Father Charles Coughlin spread antisemitic conspiracy theories, praised fascists and suggested Jews deserved the horrors of Nazi persecution.

Now, nine decades later, his church is officially declaring him an antisemite — and educating visitors about his legacy of hate.

Following renewed interest in Coughlin and two years of discussions with local Jewish figures, the National Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan, has changed the way it memorializes its founder, whose large national following helped pay for its construction.

Previously, official histories at the Catholic parish seat stated that Coughlin’s “political involvement and passionate rhetoric opened him up to accusations of antisemitism.” The new version, posted on both the church’s website and on an updated plaque on the Shrine grounds, is far more direct, stating clearly that Coughlin himself propagated antisemitism.

“His political involvement and passionate rhetoric gradually became overtly anti-Semitic,” the new passage reads, with the updated plaque in the church now including a QR code to a page on the Shrine’s website. Entitled “Legacy of Anti-Semitism,” the page discusses Coughlin’s record of antisemitic comments in the late 1930s in more detail, including his national distribution of the notorious antisemitic forgery “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” which purports to be a secret plan for Jewish world domination.

Housed in a historic Art Deco building, the Shrine will be celebrating its 100th anniversary in 2026. But almost 60 years after Coughlin’s retirement, many members of the church community had never heard of him or his legacy among Jews.

The Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan on May 31, 2022, before a “discussion of the Jewish-Catholic Relationship”. This event was co-sponsored by the Detroit JCRC/AJC and the Archdiocese of Detroit. The Shrine was founded by Father Charles Coughlin, who had an antisemitic radio show in the 1930s. (Jeff Kowalsky/JTA)

Detroit’s Jews, many of whom live within a few miles of the church, have petitioned the Shrine for years to better acknowledge its painful history. For them, the change was significant.

“It’s a total victory,” Levi Smith, vice president of a local foundation devoted to the historical legacy of Detroit Jewish architect Albert Kahn, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Smith said he helped work with the church on the new language, “and I made a couple of new friends, which was really nice.”

Don Erwin, a Shrine parishioner who also worked on the revised language, said he was “thrilled” that the changes were made. “I think it’s very important that the Shrine deals with the antisemitism of Father Coughlin,” he said. “It’s such a legacy that we really haven’t dealt with.”

In recent years, podcasts, documentaries and new histories of the time period have made note of the similarities between Coughlin’s brand of fascist populism and modern political figures’ reach on social media. And the Shrine has taken steps to grapple with Coughlin’s antisemitism.

In 2020, the Shrine’s then-head pastor took the opportunity of his New Year’s Eve sermon to apologize for Coughlin’s words and actions toward the Jews. And in 2022, Smith and other local Jewish historians and activists attended a discussion on Jewish-Catholic relations held at the church, spearheaded by the local Jewish Community Relations Council and the Archdiocese of Detroit. The event was an attempt to heal the old wounds struck by Coughlin and by his remaining loyalists in the church.

But many Jews in attendance were dismayed to find that, in the midst of interfaith dialogue in which even the Shrine’s own staff admitted Coughlin was antisemitic, the version of history captured on the church’s grounds still spoke of “accusations of antisemitism.”

Father Charles Coughlin speaks at a rally in Cleveland, Ohio, on May 10, 1936, in support of his isolationist political third party. Coughlin used rallies such as these to spread his antisemitism beyond the airwaves. (Bettmann via Getty Images)

A revision was already in the works, Shrine staff and parishioners said at the time. They brought Smith and other Jews into discussions about what should be said about Coughlin, and how the church should frame his legacy more than 80 years after the height of his infamy. The changes were then approved by the Archdiocese, the same body that had condoned Coughlin’s antisemitism for years as he spewed it from the airwaves.

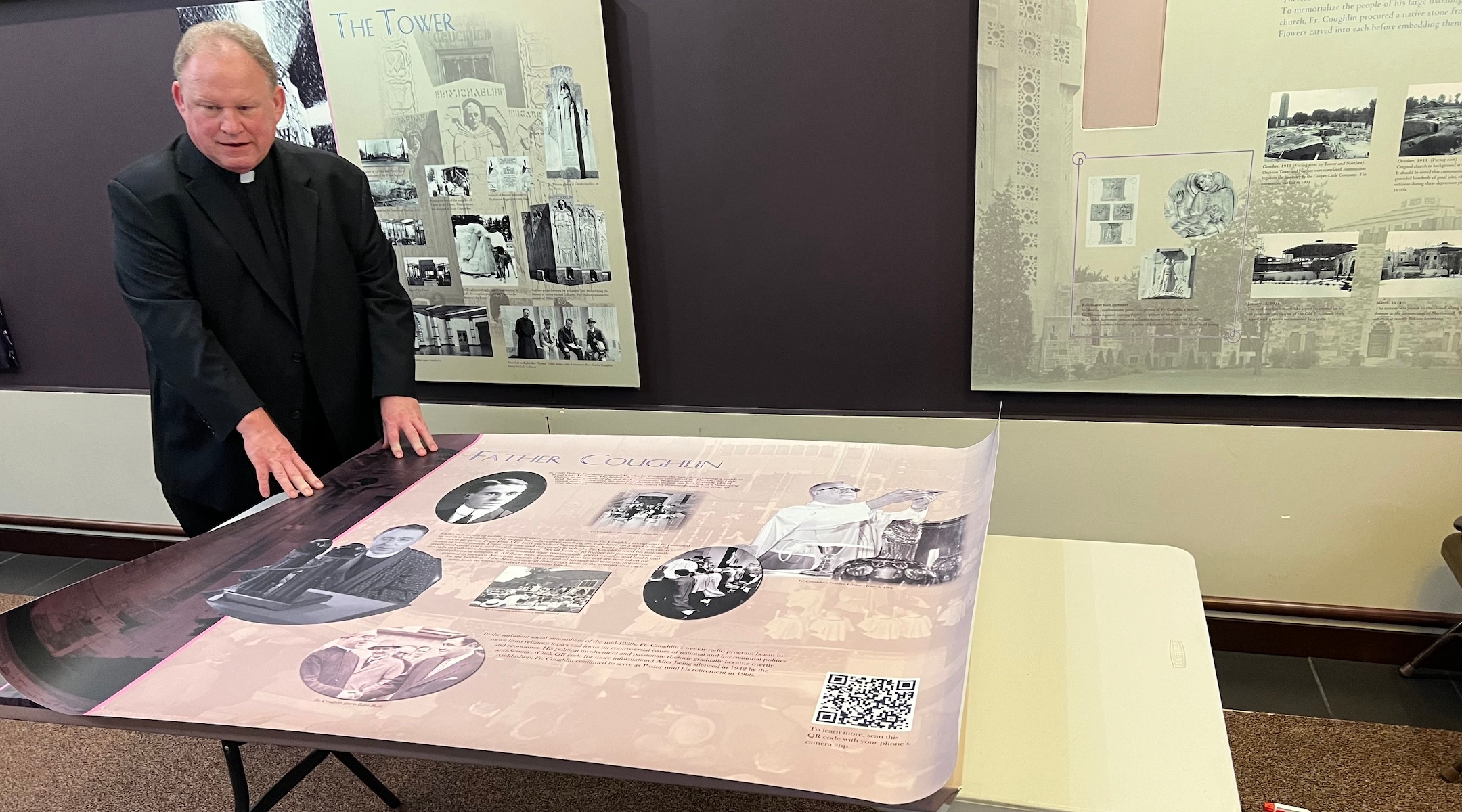

“We can’t erase our past, but we should learn from it,” Rev. John Bettin, current head pastor at the Shrine, told JTA. “All we can do is look at our mistakes and follow through that and do better in the future.”

Bettin is relatively new to the Shrine, which has undergone significant staff turnover in recent years. He joined the parish in July 2023, after the revisions were already underway, and was not involved in their drafting. Yet he said he agreed with the decision to change the material and, when the new plaque and website went up in November, offered a blessing. Smith, meanwhile, recited the Shehechiyanu, a traditional Jewish blessing to mark special occasions.

The new plaque went up in November, as antisemitism across the country was spiking following the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war, though parties involved said the timing was unconnected. Smith has asked Bettin to write a notice about the change in the parish bulletin, but such a column so far has not been published. Bettin said he still intends to write the column, but that so far he has been limited by space.

In his hopes for the Shrine’s future, Bettin said he wants the congregation to focus less on Coughlin and more on the message of Christianity promoted by St. Thérèse of Liseaux, the saint referred to as the “Little Flower” for whom the parish is named. Still, some more educational activities are in the works, including a possible church trip to the local Holocaust museum — which contains a small section on Coughlin.

The Jews who worked with Shrine on the change hope it will help heal a small part of their local community.

“Before, we would be afraid to go in it,” Smith said. “Now it’s a friendly place.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.