In December of 1912, Nathan Goldfarb, a Jewish watchmaker in New York, had an affair with a boarder who was staying in his home named Minnie Schechter. After Goldfarb’s wife, Lena, caught the wayward couple in the act, the pair absconded, leaving behind Goldfarb’s three children.

Lena Goldfarb, who ran a restaurant in the Lower East Side, filed a report with the National Desertion Bureau, a newly-formed social services agency that tracked down missing Jewish husbands. The bureau filed an indictment against Goldfarb for child abandonment, numbering the case M7, one of its earliest investigations.

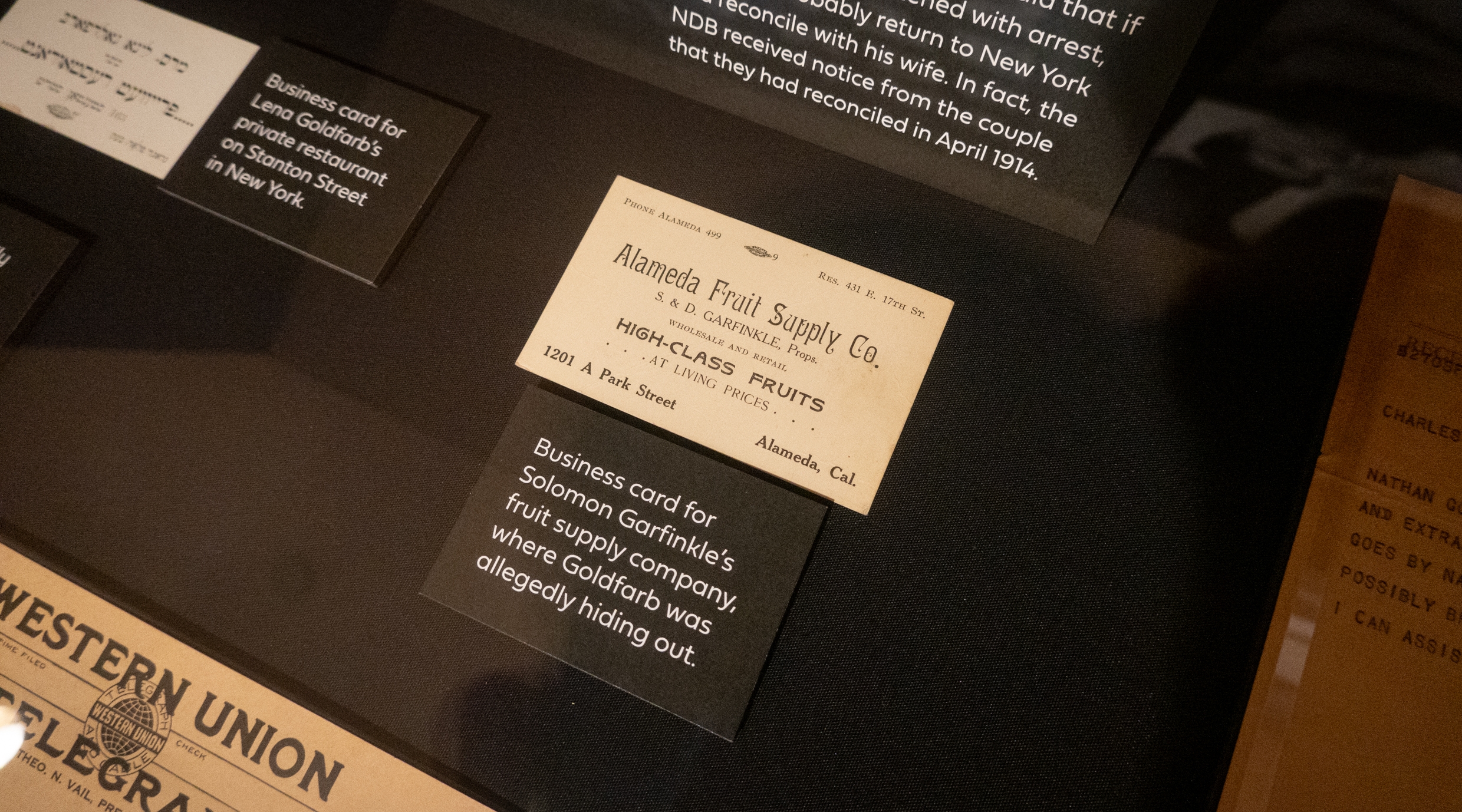

The bureau tracked the missing couple down to Alameda, California. Investigators found that Goldfarb and Schechter were living in a fruit shop owned by a man named Solomon Garfinkle and were participating in what a local contact told investigators appeared to be “sort of an amateur and miniature free love colony.”

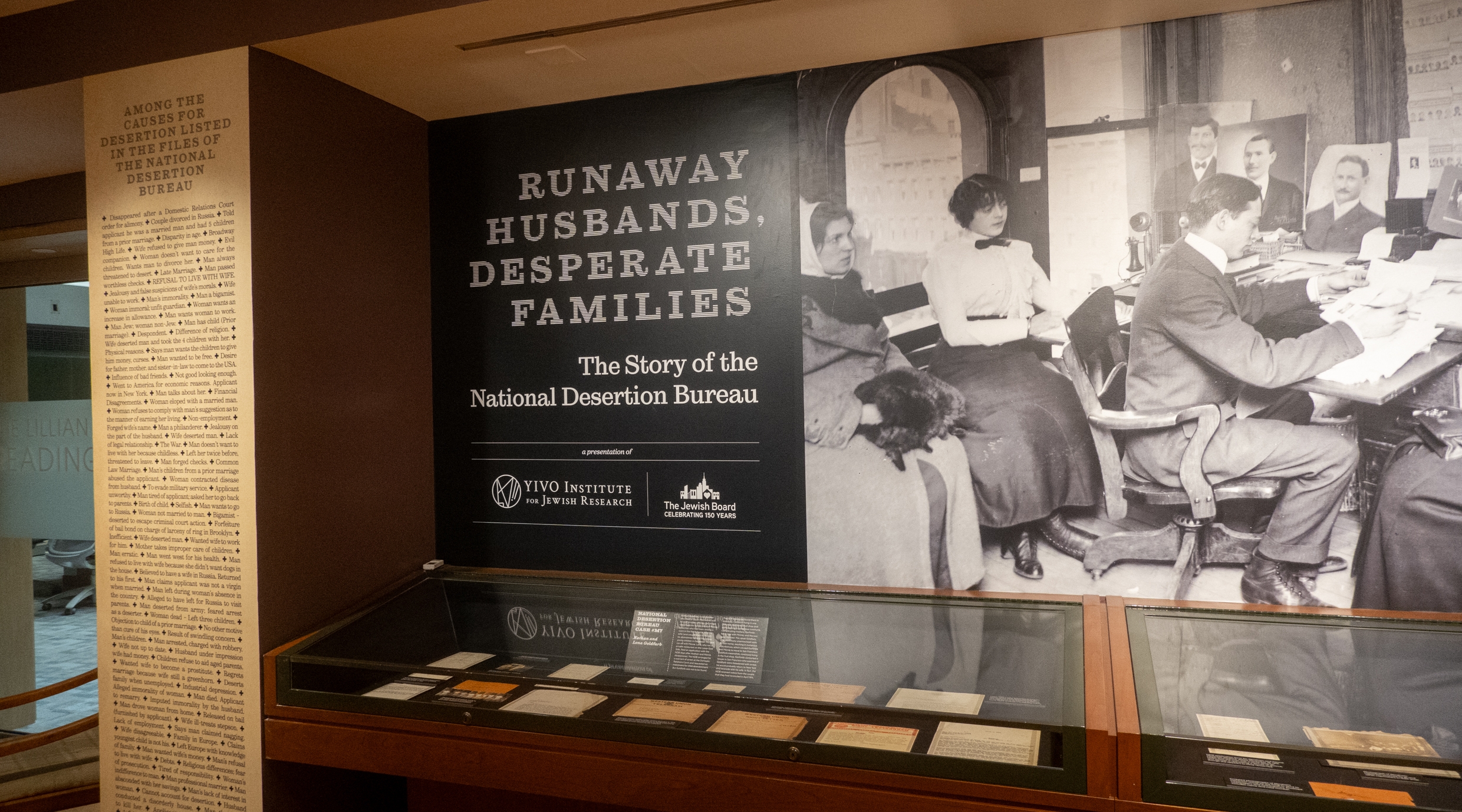

The Goldfarb affair — one of 18,000 case files recorded by the National Desertion Bureau in the archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research — is just one of the stories featured in a new exhibit about the bureau, “Runaway Husbands, Desperate Families: The Story of the National Desertion Bureau” that opens Monday at YIVO’s headquarters at 15 West 16th St. in Manhattan.

A collaboration between YIVO and the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, a social services agency, the exhibit provides rich insight into the lives of early Jewish immigrants to the U.S. Organizers hope the show will help viewers recognize and grapple with the complexities of Jewish immigrant life in the early 20th century — and foster empathy for migrants and refugees today.

“Human history, family history is just a lot more complicated than any of us have wanted to own and talk about — no one wants to talk about their great-grandfather who abandoned the family; we want to talk about the great-grandfather who started a business,” the CEO of the Jewish Board, Jeffrey Brenner, said in an interview. “There’s been a lot of damage over the years. It’s time we talked about the full richness of human experience, rather than just truncated hero stories.”

The Jewish Board approached YIVO about launching the exhibition as part of a history project marking the 150th anniversary of the board’s predecessor, United Hebrew Charities, which was established in 1874. YIVO agreed, believing the archives are a “fascinating collection that reveals a lot about aspects of Jewish immigration that don’t typically get discussed,” said Eddy Portnoy, YIVO’s director of exhibitions.

The exhibition includes photos of the missing husbands and ephemera from the time, including correspondence between investigators and business cards for both Lena Goldfarb’s restaurant and Solomon Garfinkle’s shop advertising its “high-class fruits.”

Exhibit on the National Desertion Bureau at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in Manhattan, June 14, 2024. (Luke Tress)

The Jewish Board also believes enough time has lapsed that viewers can take in the exhibit — and look at their own family history — with a dispassionate eye.

“People can look at this history of their family in perspective,” said Gavin Beinart-Smollan, a history consultant for the Jewish Board. “The goal is for all of us to have compassion for these people, to understand where they came from.”

The National Desertion Bureau had its roots in the waves of immigrants who arrived in New York in the late 1800s. The new arrivals faced discrimination and struggled to make ends meet. Some destitute mothers turned their children over to orphanages run by United Hebrew Charities, mainly because their husbands had abandoned them, Brenner said.

In response, the charity group pushed for legislation that created the New York family court system and compelled men to pay child support, and to make it a felony to abandon children. The felony charge meant men could be extradited across state lines for leaving their families — but first, the missing husbands needed to be located. United Hebrew Charities formed the National Desertion Bureau in 1911 to find the men and help their wives file charges against them.

The issue of abandonment was widespread in the immigrant world of early 1900s New York, common enough that well-known psychics in the Lower East Side specialized in divining the whereabouts of missing men. Reasons for leaving families varied, but the most common appeared to be other women. Other reasons recorded by the bureau include criminality, “influence of bad friends,” “Broadway high life,” “to evade military service” and “did not like Baltimore.” Sometimes women left their husbands due to “cruelty” or “barbarity,” a euphemism for domestic violence, and sought the bureau’s help obtaining child support.

A common denominator among all the cases: the hardship of arriving in a new country. Many immigrants lived in cramped tenement apartments with their families, working long hours, six days a week, and divorce was expensive.

“The underlying cause of a lot of this desertion is poverty, the immigrant experience, the dislocation of immigration,” Beinart-Smollan said.

“It was very easy to disappear back in the days before social media or the internet,” he added.

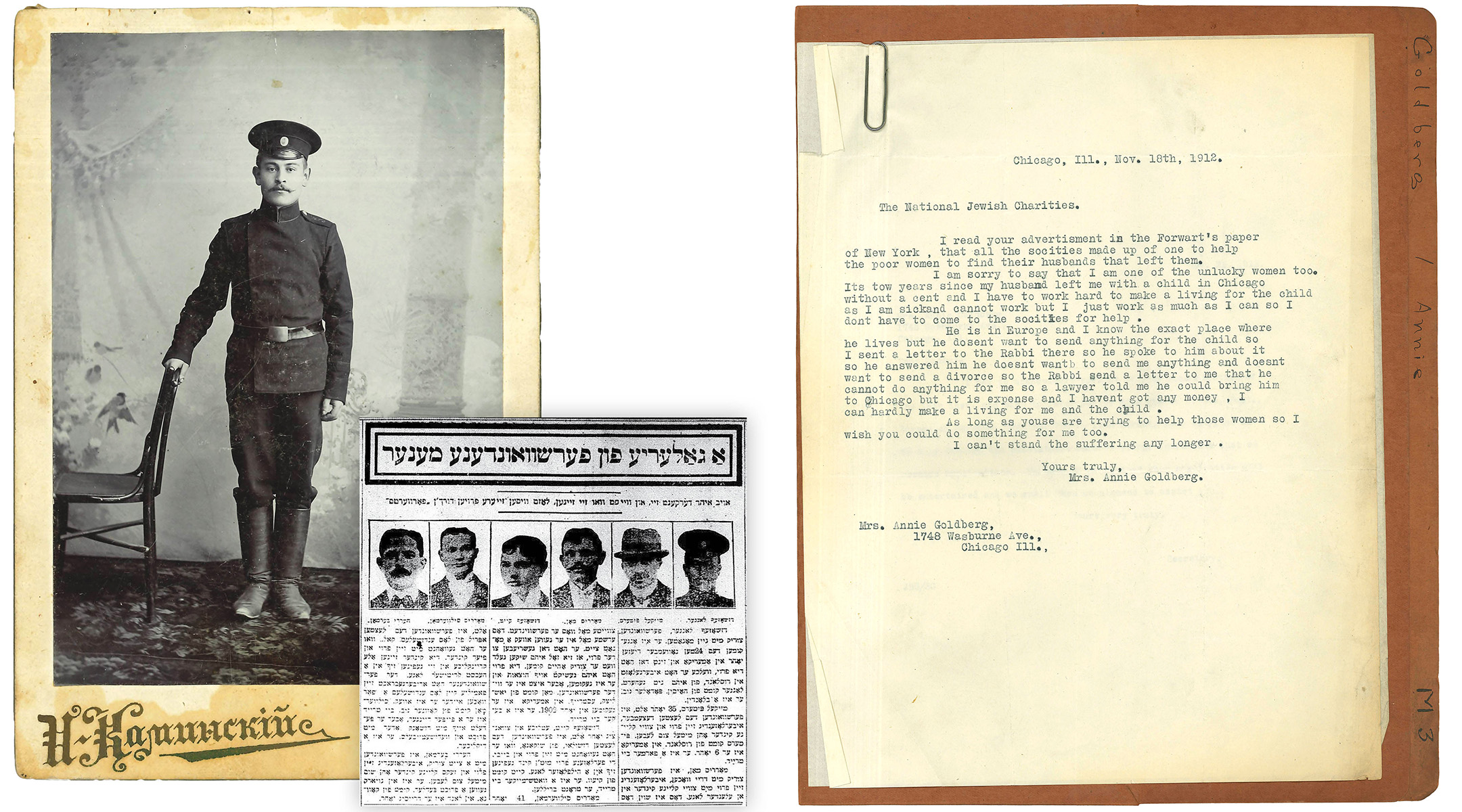

One letter to the bureau, signed by Mrs. Annie Goldberg and dated November 1912, describes how her husband left her and moved to Europe. She knew his location and appealed to a local rabbi for help, but her husband refused to send support.

“As long as youse are trying to help those women so I wish you could do something for me too,” Goldberg wrote from her home in Chicago. “I can’t stand the suffering any longer.”

Left: A photo from a National Desertion Bureau case file of Joseph Langer, a missing husband during his service in the Russian Army, and a Forverts Gallery of Missing Husbands published on September 15, 1912. Right: A letter from Annie Goldberg requesting help after being abandoned by her husband. (Courtesy/YIVO Institute for

Jewish Research)

To find the men, the National Desertion Bureau worked with the Yiddish Daily Forward, the leading Yiddish newspaper then known as the Forverts, to publicize the cases. Starting in 1908, the Forward ran a regular column called “The Gallery of Missing Husbands” that had photos, descriptions and stories about the missing men, provided by their wives.

Readers who spotted the missing men would report their whereabouts to the bureau. In one case, a missing husband had remarried without telling his second wife about his first. The second wife’s brother recognized the man in a newspaper and wrote to the National Desertion Bureau, providing them with key information about his location.

Investigators were also set on the trail, interviewing the missing men’s business partners and neighborhood acquaintances to try to glean information about where they may have gone. The bureau also had a network of feelers across the United States who could ask around about a missing husband who was suspected to be in the area, and worked with social services agencies around the world to try to track them down.

The men ranged near and far. Some moved from the Bronx to Brooklyn, while others landed in Chicago, St. Louis or Los Angeles. Others went abroad, including returning to Eastern Europe. The case files contain correspondence between the bureau and Jewish organizations in Argentina which helped track down men there. The vast majority of the cases were tied to New York, but stretched to nearly 50 countries and every U.S. state except Hawaii.

One case file contains an exchange between a bureau investigator and a Jewish community contact in San Francisco, for example. The investigator inquires about a missing husband and his lover who were believed to be in the area; the San Francisco contact replies that the man was spotted in a small town riding a bicycle down a street.

“There are these really interesting little details about what’s going on in these people’s lives all told through this correspondence,” Portnoy said. “It’s really kind of an unusual look into Jewish immigrant life that, as far as I know, no other archive provides.”

Abandonment did not appear to be more prevalent in Jewish communities than other immigrant groups, but what differentiated Jews was how they tackled the issue, looking at it as “a large-scale social problem related to immigration,” Portnoy said.

Exhibit on the National Desertion Bureau at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in Manhattan, June 14, 2024. (Luke Tress)

“It was social workers that provided the impetus for the creation of this organization,” Portnoy said. “The Jewish community handled this with a much more modern sensibility than the other immigrant communities.”

Other groups, such as Catholic communities, dealt with missing husbands on a case by case basis and did not allow divorces. By contrast, the bureau helped women file for divorce if that’s what they wanted. And while the majority of the bureau’s cases were Jewish families, it handled cases for other groups as well, such as searching for men from the Puerto Rican community. Most of the cases involved Yiddish speakers, but some Sephardic Jews turn up in the files as well.

The Jewish Board and YIVO both said they had not received significant pushback against exploring a more unsavory chapter of Jewish history. Organizers said they had chosen files that were at least 100 years old, meaning those involved are almost certainly deceased.

“I actually hope that people do find things out about their family, whether or not it’s good or bad,” Portnoy said. “I hope that they discover aspects of Jewish life of the immigrant generation, of the difficulties of immigration that they may not have known about.”

He added, “The details are sometimes kind of juicy but they’re not that terrible.”

Organizers plan to release a genealogy database of the case files in November that will be freely accessible to the public and researchers.

The exhibit also has lessons for the present day, Brenner said.

“Jews have sometimes been held up as model immigrants, like we were perfect people, had perfect stories and we pulled ourselves up by our bootstraps,” Brenner said. “The real story is actually a lot more complicated and a lot of us struggled and had a really hard time, so we think it helps us all have a lot more empathy for both current immigrants but also just people in poverty.”

The bureau was most active from its founding in 1911 through the 1940s. Immigration restrictions that tightened in the 1920s and then the Holocaust put a stop to new Jewish arrivals in New York. The bureau downsized, rebranded as the Family Location Service in 1954, then merged with the Jewish Family Service, another aid group, in 1966. The nature of that group’s work in its latter period is unclear and records are lacking, Beinart-Smollan said. In 1978, the Jewish Family Service merged with the Jewish Board of Guardians to form the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services.

It’s unclear how often the bureau successfully tracked down and prosecuted missing husbands, since researchers are still in the process of exploring and digitizing the archives. Many of the couples reconciled on their own after the wife filed an application with the bureau, for example, if the man saw his face in the newspaper and was shamed into returning home.

Sometimes, other circumstances prevailed.

After watchmaker Goldfarb and his lover Schechter eloped to California, Schechter fell for Garfinkle, the owner of the fruit shop. The pair got married and moved across the bay to San Francisco, leaving Goldfarb behind in the shop.

Goldfarb was left distraught and repeatedly made unannounced visits to the newlyweds’ home, sparking fights among the trio. Garfinkle contacted a lawyer, who advised him that if Goldfarb were threatened with arrest, he would probably reconcile with his wife. The National Desertion Bureau received notice that the couple had gotten back together in April 1914.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.