When David Levy resigned as Israel’s foreign minister in 1999, he finally received what had long eluded him: center stage in Israeli politics. His break with Benjamin Netanyahu, then serving his first term as prime minister, focused global attention on the glacial pace of an Israeli-Palestinian peace process even then on life support.

The Moroccan-born construction-worker-turned-politician first entered the public eye when then-Prime Minister Menachem Begin appointed him to the Cabinet in 1977. Intent on gaining more power for himself and economic benefits for the Middle Eastern and North African Jews whom he represented, Levy often used the threat of resignation.

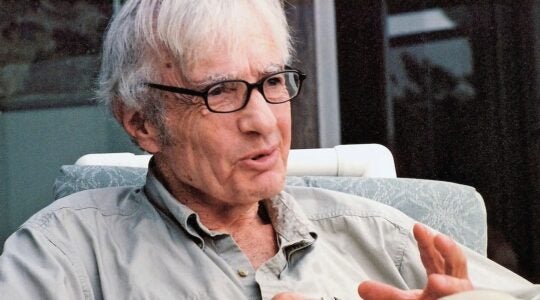

Levy, who died Sunday at age 86, came to reflect the anger of Mizrahi Jews in Israel, often treated as an underclass by the Ashkenazi elite who dominated Israeli politics in its first decades. Long before Aryeh Deri, the Moroccan-born leader of the fervently Orthodox Shas Party, came to personify Mizrahi grievances, Levy was their voice in high places.

Levy built his career from the grassroots, using his experience in construction to become a political activist and a labor leader. And it was this working-class background that served Levy as he rose in the ranks of Likud, Begin’s hawkish opposition party. Starting in the late 1970s, he held numerous posts in the party, including stints as housing minister and deputy prime minister, as well as foreign minister in the government of Yitzhak Shamir.

When he appointed Levy to the Cabinet, Begin said it was “a gesture of gratitude to our brethren, the Middle Eastern Jews, who supported us.”

Levy also cultivated a street-fighting style that characterized his political machinations. In 1992, just a few months before elections, Levy came close to resigning from Shamir’s government after some of his Mizrahi allies were relegated to low positions in Likud’s lineup of candidates for the Knesset.

Levy had ideological differences with Likud. Before he formed the Gesher Party in 1995, he had long been the strongest voice in Likud for his working-class constituency, and continued his fight for more social-service programs in the governing coalition. Gesher won five Knesset seats in the 1996 elections.

Levy was also a moderate amid a sea of hard-liners. At the peak of the 1982 Lebanon War, he was among the few who spoke loud and clear in favor of an Israeli pullout. Before resigning in 1999, he refused to accompany Netanyahu to his meetings with U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, saying the discussions were a waste of time unless the premier came armed with specific proposals for a further exit from the West Bank.

He also decried the “rampage and hooliganism” of many on the right in the run-up to the 1995 murder of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin by a far-right Jewish assassin.

Levy’s personal dispute with Netanyahu dated back to 1991, when Shamir bypassed him to be his second in command at the opening round of the Middle East peace talks in Madrid. Shamir’s choice: Netanyahu, Levy’s deputy in the Foreign Ministry. Netanyahu had a political charisma that Levy lacked: Netanyahu is fluent in English, a language that Levy did not speak.

Netanyahu remembered his old rival this week as a fighter for fellow North African and Middle Eastern immigrants.

“David, born in Morocco, forged his way through life with his own two hands,” Netanyahu said. “On the national level, he made a personal mark on the political world, while taking care of weak populations that knew adversity.”

Opposition Leader Yair Lapid praised Levy as a trailblazer in representing citizens on what Israelis call the “periphery.”

“He brought to the Knesset the voice and representation of the development towns that were so lacking in it, and in his fight for a fairer and more equal society, he became an important Israeli symbol within his lifetime,” said Lapid, a former prime minister.

Levy too dreamed of becoming premier. When Begin resigned in 1983, Levy made a dramatic announcement: “Menachem Begin,” he exclaimed, “you have got yourself an heir.” But over the years, he repeatedly lost his campaigns to become the Likud’s top candidate, declaring at one point, “I have realized that the movement in which I was raised and in which I had invested all my life, is not ripe to be led by a Moroccan.”

For much of his career, Levy was often the butt of jokes for his pugnacious speaking style and accusations, perhaps reflecting the snobbery and bigotry of his better-educated rivals, that he was an intellectual lightweight. His revenge came at the ballot box, and in 2018, Levy won the Israel Prize for lifetime achievement.

After his resignation as foreign minister, Levy was elected as a member of the Knesset in 2003, but in subsequent elections his party did not win enough votes to keep him in government.

Levy lived in Beit She’an. He is survived by his wife Rachel Edri; 12 children, including a daughter, Orly, a former member of Knesset and minister for community empowerment and advancement, and a son, Jackie, who was elected mayor of Beit She’an. He was said to have at least 40 grandchildren.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.