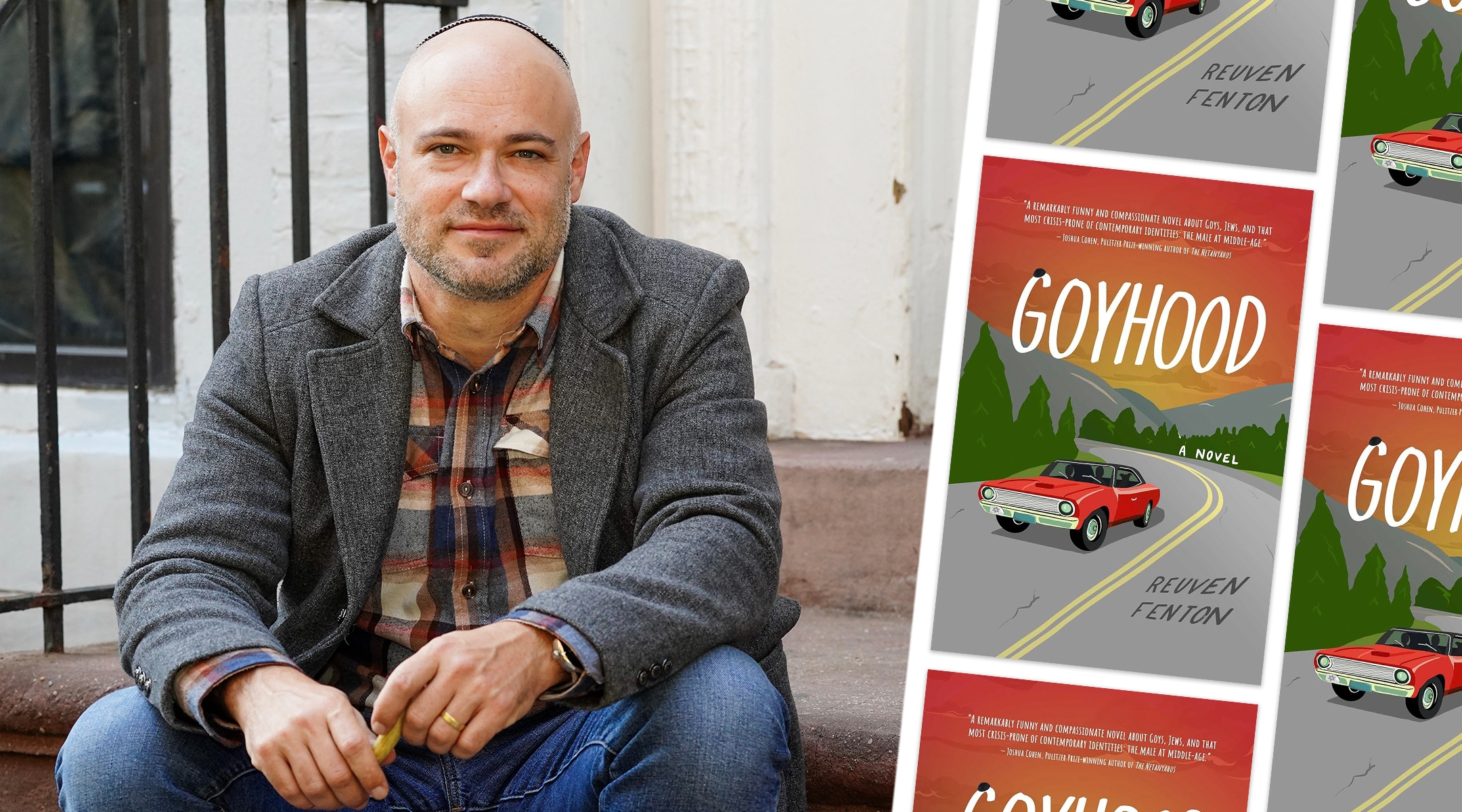

What would happen if a devout Orthodox Jewish man discovered in middle age that he is not actually Jewish, at least according to rabbinic law? This “what if” scenario is the premise of the debut novel “Goyhood” by journalist Reuven Fenton, who is an observant Jew himself.

A reporter for the New York Post since 2007, Fenton, 43, previously published a nonfiction book, “Stolen Years: Stories of the Wrongfully Imprisoned” in 2015. He also wrote a young adult urban fantasy novel that was never published. Fenton told the New York Jewish Week that he had more success writing “Goyhood” because, while the book is fiction, he drew upon his own journey of self-discovery and coming to terms with who he is as a Jew.

In the novel, Martin and David Belkin are twin brothers growing up in the small, fictional town of New Moab, Georgia. When they are 12, a new rabbi in town knocks on their door to tell them about Chabad — and their mother casually informs them that they are Jewish. Martin readily embraces his new identity: He becomes religious, changes his name to Mayer, and eventually moves to New York to study at a top yeshiva in Brooklyn and gets married.

When the twins are in their early 40s, their mother dies by suicide, leaving her sons a letter confessing that she lied about being Jewish. Their father, who died when the twins were young, was Jewish, but according to rabbinic Jewish law, Judaism is passed through the mother.

While mourning their mother, David convinces his distraught brother to go on a road trip through the Deep South, suggesting that because they are not, technically, Jewish, they are no longer bound by the rules of the seven-day mourning period of shiva. What follows is an adventure that is as outrageous as it is introspective, and draws upon big themes like what it means to be Jewish in the U.S. and what it means to participate in American society at large.

In real life Fenton — who is one of the New York Jewish Week’s 36 to Watch this year — hails from two Jewish parents, though his family wasn’t religious when he was young. However, around the time he was 11 or 12 years old — the age that Mayer finds religion in the book — Fenton’s parents became Orthodox through the Chabad in his hometown of Lexington, Massachusetts. “There’s definitely a connection, although I would say it was a semi-conscious connection,” Fenton said. “It wasn’t something that I was dwelling on too hard, but it’s obvious to me that there is a parallel.”

From that point, Fenton was schooled in religious institutions: He attended an Orthodox Jewish high school and studied English at Yeshiva University. It wasn’t until he got his master’s degree at Columbia Journalism School that he had his “first real exposure to the world outside the Jewish bubble,” he said. “I remember thinking that at the time. I was hyper aware of it.”

Fenton has been involved “in the secular world” for many years now — his reporting for the Post has him crisscrossing the five boroughs, obtaining an in-depth knowledge of many neighborhoods and communities. “But at the time there really was this step outside my comfort zone,” he said. “There’s a culture among Jews. There’s a Jewish way that you’re accustomed to that you don’t get out there and you feel it.”

By that, he means speech patterns and cadence, body language and even hobbies, interests and food preferences — in addition to shared religious practices. “In the secular world, you’re anonymous. You can decide how much you want to share about yourself with the people around you,” Fenton said. “But if you’re in the Jewish bubble, there really are no strangers. Even if you meet someone for the first time, that person already knows so much about you because you have a shared background, a shared culture.”

Fenton considers himself Modern Orthodox in practice because he wears casual clothing, has worldly knowledge and loves popular culture. Spiritually, however, he said he is more of a Hasidic Jew — he is drawn to the Hasidic philosophy that one is in this world to do as many good deeds for other people as you can without fixating on the afterlife.

This philosophy resonates with the main character in “Goyhood”: At the start of the book, Mayer subscribes to the concept of “schar,” which means the more Torah you study, the more spiritual currency you acquire. As the novel progresses, however, Mayer moves away from this kind of thinking. Through the road trip with his brother, Mayer meets new people — including Charlayne, a brand ambassador in her early 30s who has more in common with Mayer than he initially thought — and he starts to participate in the world and open himself up to others.

“The purpose is what’s happening here on earth, right now, and what you can do specifically for other people,” Fenton said. “I steer Mayer in that direction, in terms of him realizing during the story as he starts to participate in this world. He’s actually getting involved in people’s lives once again. He hasn’t done that for 25 years and as he’s doing that, he’s starting to realize that there’s actually more to all this. There’s even a scene where he’s hiking up the Appalachian Trail and looking at all the natural beauty and he realizes it would never have occurred to him that taking a walk in the woods is actually an opportunity to worship.”

But “Goyhood” isn’t about one man’s journey away from observant Judaism and toward finding himself; it’s not “Unorthodox” from a male perspective. Instead, it’s about learning not to build walls around yourself and finding a role in the world that ideally benefits society. “Self improvement is meaningless if it only improves the self,” Fenton said. “This, I think, is Mayer’s key takeaway by the end of the book.”

Fenton — who has seven siblings in real life — said he created the relationship between twins Mayer and David to represent the two sides of himself. “There’s a split inside me between the secular and the religious,” he said. “It has a lot to do with the abruptness of the transition in our family to becoming Orthodox when I was a kid. I objected to it. I wasn’t comfortable with the changes happening so quickly in our lives … because when you become Orthodox, you give up things.”

That journey “started a theme in my life,” he said. “It’s mellowed out quite a bit in my adulthood, but I think it’s still there, this yearning for the secular even as I appreciate and I embrace Judaism.”

Fenton points to a popular kabbalistic concept: Every Jew has two souls, a godly soul and an animal soul. “That might be the best parallel,” he said. “David is like the animal soul inside me, the soul that’s impulsive and yearns for physical things. The godly soul inside me is Mayer, obviously, who is drawn towards purity and religiosity and torah study. These two forces do battle inside me.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.