This article is also available as a weekly newsletter, “Life Stories,” where we remember those who made an outsize impact in the Jewish world — or just left their community a better or more interesting place. Subscribe here to get “Life Stories” in your inbox every Tuesday.

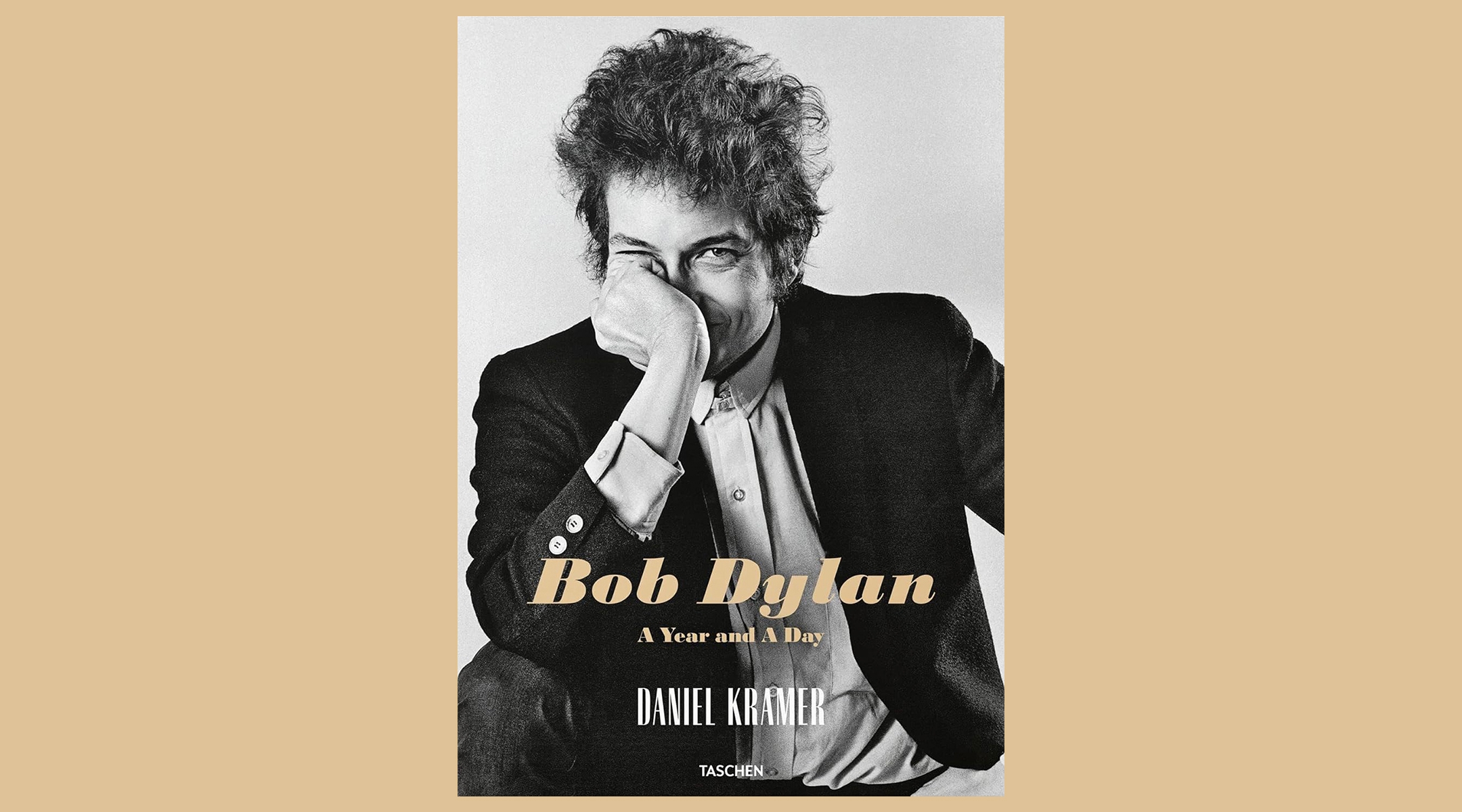

Daniel Kramer, 91, Bob Dylan’s photographer and alter ego

Photographer Daniel Kramer, who served as Bob Dylan’s unofficial staff photographer during a pivotal year in the singer’s evolution from folkie to rock star, died April 29 in Melville, New York. He was 91.

Kramer had unprecedented access to Dylan for a year that included the release of the 1965 album “Bringing It All Back Home,” Dylan’s first to (controversially) incorporate electric instruments. Kramer shot the enigmatic cover photo for the album, as well as thousands of intimate, unposed images of the singer at work and play.

Born in Brooklyn, Kramer apprenticed under legendary photographers Diane Arbus and Philippe Halsman. “Everything about us was the same,” Kramer told the Forward in 2023 about his relationship with Dylan. “Jewish, parents, what your father did for a living, everything. We were like cousins. Working with Dylan was like working with me. That’s why we got along; we were crazy.”

Lesley Hazleton, 78, the agnostic writer who couldn’t forget Jerusalem

Author Lesley Hazelton’s last book was “Agnostic: A Spirited Manifesto.” (Penguin Random House)

Born to an observant Jewish family and educated at a Catholic school, Lesley Hazleton was 20 when she left Britain in 1966 for Jerusalem.

There she earned her master’s degree in psychology from the Hebrew University and worked as a journalist for the Jerusalem Post and Time magazine. She wrote a classic book about feminism in Israel — “Israeli Women: The Reality Behind the Myths,” published in 1977 — before moving to New York in 1979.

“I sold the house when I left Israel, exhausted by the constant high level of tension and drama there,” she wrote in 1986. “After too many wars — and the ecstatic high of one peace — I hungered for normality. Yet I don’t seem to be very good at normality. I wander through it, thinking of Jerusalem.”

At least two more careers were ahead of her: She began driving race cars and writing an automotive column (“Confessions of a Fast Woman,” a memoir, came out in 1992), and she wrote books about faith and spirituality, including biographies of the Virgin Mary, the biblical Jezebel and the prophet Muhammed. She also penned a memoir, “Agnostic.”

Hazleton once described herself as “a Jew who once seriously considered becoming a rabbi, a former convent schoolgirl who daydreamed about being a nun, [and] an agnostic with a deep sense of religious mystery though no affinity for organized religion.”

She died on April 29 at her home, a houseboat in Seattle. She was 78.

Sam Rubin, 64, a Hollywood reporter who got under Mel Gibson’s skin

Sam Rubin reported on the entertainment industry for over thirty years. (KTLA)

In a city of fragile egos and petty rivalries, it seemed everybody loved Sam Rubin, the longtime entertainment journalist for KTLA in Los Angeles known for his celebrity interviews and red-carpet stakeouts. Everybody, that is, except Mel Gibson: In 2006, Gibson grew irritated when Rubin asked the actor about his antisemitic rant during his arrest that year on suspicion of drunk driving. Gibson lashed out at the Jewish reporter, saying, “I gather you have a dog in this fight? Do you have a dog in this fight? Or are you impartial?”

Rubin died May 10 in Los Angeles at age 64. Accolades poured in for the San Diego native. “He made you feel special every single time, and I am not the only person who felt that warmth,” said actor Henry Winkler. “When you were being interviewed by him, there was nobody after you, there was nobody before you at that desk. It was you in that seat, and that was all that mattered.”

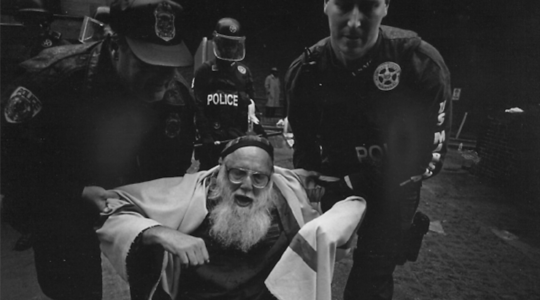

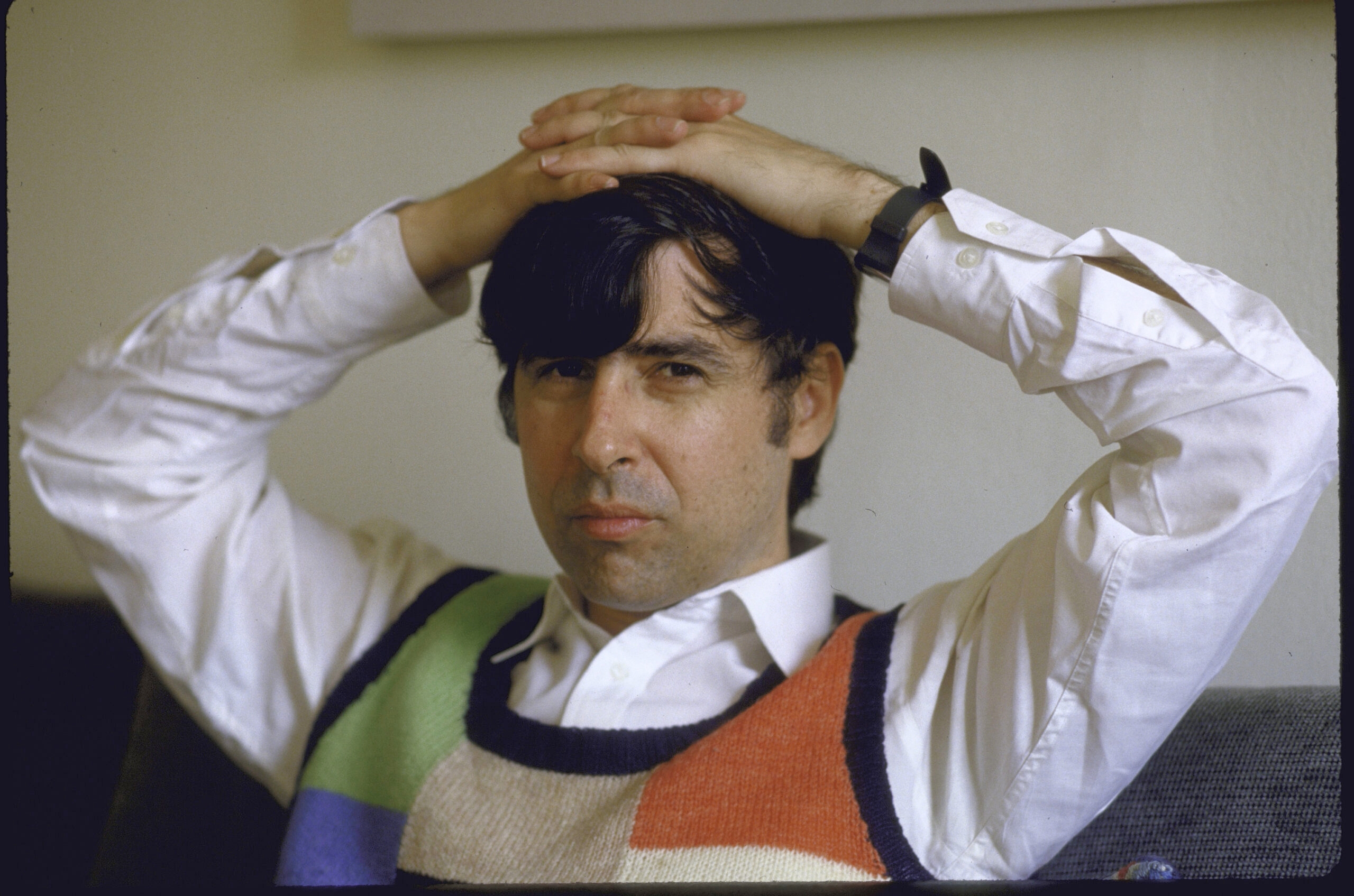

David Shapiro, 77, a student activist and poet of the New York School

Poet David Shapiro, seen here in 1986, was also a violin prodigy and art historian.(Bill Foley/Getty Images)

Before he became known as a leading poet of the famed New York School, David Shapiro was already notorious for an iconic photo of the 1960s. During the landmark 1968 student uprising at Columbia University, Shapiro was the one wearing sunglasses and puffing on a cigar, sitting behind the desk in the student-occupied office of the university’s president, Grayson Kirk.

In the 1970s, Shapiro returned to Columbia to teach English and comparative literature, having already written (at 18) the first of some 20 volumes of poetry and literary and art criticism.

Born and raised in Newark, New Jersey, Shapiro was the grandson of renowned cantor Berele Chagy. “There are parts of me that have come out of the sanctity of Jewish liturgy,” Shapiro told Tablet in 2017. “This is strange because most of my generation was extremely, extremely secular. In my work, you see this other force, a field of force.”

Shapiro died May 4 in the Bronx. He was 77.

Ivan Wolkind, 56, a Jewish professional who died on the verge of another career milestone

Ivan Wolkind was COO and CFO of Jewish Federation Los Angeles, where he worked for 13 years. (Courtesy Magen Am)

Ivan Wolkind, who was recently tapped as the new CEO of the Holocaust Museum Houston, died suddenly in Los Angeles. He was 56.

A native of England, Wolkind spent 13 years at the Jewish Federation of Los Angeles, serving as chief operating and chief financial officer. Since 2023, he had been CEO of Magen Am, a Jewish nonprofit providing armed security services to institutions on the West Coast. He was also a reserve police officer in the LAPD, an avid skier, a practitioner of yoga and a Johnny Cash fan.

In a statement announcing his new position at the museum, Wolkind said he was looking forward to fulfilling its “vision of a society that transforms ignorance into respect for human life, that teaches the lessons of the Holocaust and reaffirms an individual’s responsibility for the collective actions of society.”

He is survived by his wife, Leah Lesch, and their three adult children.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.