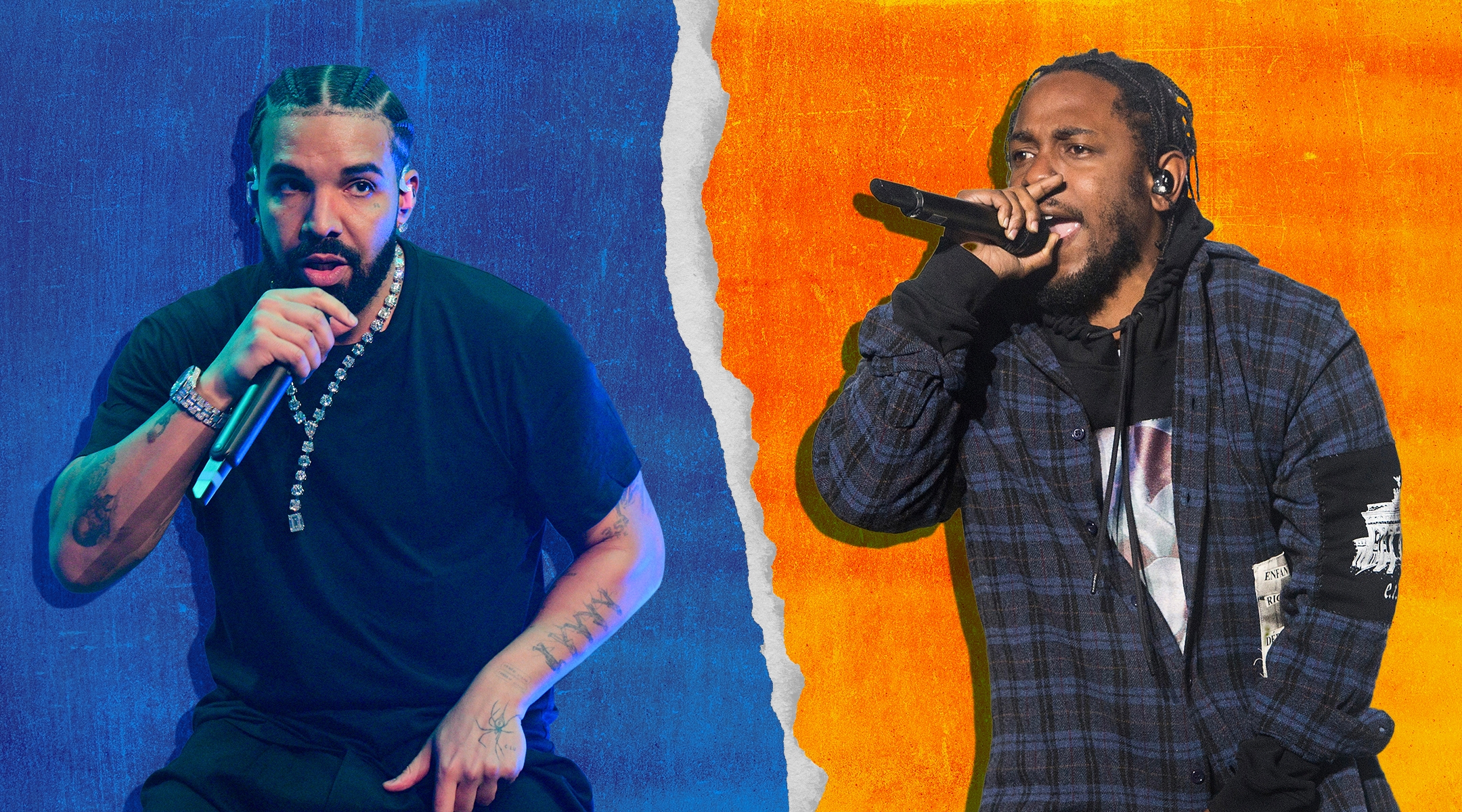

(JTA) — Breathless headlines have tracked the recent “Great Rap War” between Drake, a biracial Jewish Canadian rap superstar, and Kendrick Lamar, a Black non-Jewish American rap superstar.

Over the past few weeks, Drake and Lamar have bashed each other with unusually scathing, high-profile and rapid-fire diss tracks, which have garnered coverage even from flagship newspapers like the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. As a scholar of Jewish identity, race and gender in popular culture, I have followed those headlines to continue my research on Drake, one of the key performers examined in my forthcoming book, “Millennial Jewish Stars: Navigating Racial Antisemitism, Masculinity, and White Supremacy.”

My take: While it is tempting to dismiss the feud as a marketing ploy or a frivolous distraction from weightier issues, the Drake-Kendrick Lamar beef also illuminates broader patterns in the way that American society envisions rap authenticity, race, class, masculinity and Jewishness.

Within this feud, Lamar’s diss tracks have leveled two core accusations against Drake. First, Lamar references allegations that Drake may prey upon underaged girls — for example, the 2018 revelation that Drake (then 32) had initiated a close texting relationship with actress Millie Bobby Brown (then 14). Kendrick’s rap calls Drake a “pervert” and “pedophile” who “should be placed on neighborhood watch.”

Despite the seriousness of this sexual allegation, a great deal of public reaction to the feud has focused on Lamar’s second key accusation: that Drake — biracial, Canadian, Jewish, and a former teen soap opera actor who grew up middle-class — is inauthentic as a representation of rap’s essential African-American culture. Lamar’s lyrics thus highlight American society’s ongoing debates about how to define and redress cases of cultural appropriation, caricature and exploitation.

Lamar’s diss tracks extend the long-running and commonplace view that Drake isn’t Black enough, that his performances steal from Black culture and that Drake’s attempts to perform Black masculinity are offensive or pathetic counterfeit imitations. Lamar conveys these accusations through lyrics that call Drake “off-white” rather than Black, order Drake to stop saying the N-word, and inform Drake that “you not a colleague, you a f—ing colonizer” within the rap industry. Lamar also challenges Drake’s masculinity, calling him a “pussy” and a “bitch.”

This type of invective about Drake’s Blackness and masculinity has circulated nearly since Drake first broke into the U.S. rap industry in 2006-2010, and it has continued to coexist with his spectacular musical success. For example, although Drake was named Artist of the Decade by the 2021 Billboard Music Awards, a staggering number of online “Drake memes” mock him as “not really Black,” “not a real man” and “not a real rapper.”

Since long before the recent feud, the rap industry has often predicated rap authenticity on specific notions of Black American hypermasculinity, a gender style that the African American Studies scholar Imani Perry describes as “double-voiced.” This hypermasculine archetype titillates white suburban audiences with racist fantasies about hypersexual and criminal Black men, while also offering models of power and dignity to some Black men who experience powerlessness in a racist society. But whether conveying racism or Black dignity, this model of masculinity often requires dark skin, which popular stereotypes equate with harder masculinity, and an impoverished upbringing in ghettoized Black neighborhoods of American cities, such as Kendrick Lamar’s hometown of Compton, California.

In contrast to this industry norm, Drake — born Aubrey Drake Graham — is a light-skinned biracial man raised more or less middle-class by his Canadian Ashkenazi Jewish mother within an affluent neighborhood of Toronto. Drake was also a teen actor from 2001 to 2008 on the schmaltzy Canadian soap opera “Degrassi: The Next Generation,” in which he played an artistic and gentle middle-class student who eventually becomes wheelchair-bound and experiences erectile dysfunction.

In the context of American rap, all of these traits position Drake as an inauthentic Black man and thus an inauthentic rapper. For example, early in Drake’s career, CBS News’ Katie Couric illustrated the way that popular stereotypes of “soft” Jewish masculinity could undermine his rap credibility: When interviewing Drake in 2010, Couric immediately asked, “What’s a nice Jewish boy doing in a career like this?”

Even for viewers unfamiliar with stereotypes about “soft” Jewish men, Jewishness is often associated with whiteness, fueling the misperception that Jewish identity undermines authentic Blackness. Drake himself has discussed the perception: Early in his rap career, he told Heeb magazine, “I went to a Jewish school, where nobody understood what it was like to be black and Jewish.” While this miscomprehension led some of Drake’s classmates to question his Jewishness, it motivates some audiences today to question his Blackness.

But if Drake’s skin tone, class upbringing, Jewish identity and acting resume all distance him from rap industry norms, then his efforts to close that distance have often just marked him as even more inauthentic, and even as exploitative. Over time, Drake has striven to better align his image with the industry’s model of Black hypermasculinity. For example, he revealed new muscles after a regimen of bodybuilding in 2015 and he revealed his hair in new cornrows in March 2022.

Likewise, Drake has shifted towards fashion choices that evoke ghettoized Black communities and has begun to speak more consistently in African American Vernacular English, both in performances and in public appearances. However, these changes always risk coming off as contrived because Drake’s early interviews and “Degrassi” performances suggest that he grew up speaking and dressing in accordance with white Canadian middle-class norms.

Indeed, a long line of critics, including Kendrick Lamar, have disdained these changes as proof that Drake is stealing from Black culture or caricaturing Blackness in order to shore up his marketability. For example, in the recent diss track “Euphoria,” Lamar raps, “I hate the way that you walk, the way that you talk/I hate the way that you dress.” In the diss track “Meet the Grahams,” Lamar raps, “The skin that you livin’ in is compromised in personas.”

In the wake of this rap feud, time will tell how Drake may continue to modulate his relationship to rap industry conventions, and how his future self-stylings will be received by peers and audiences. But however his individual image evolves, Drake will likely remain a high-profile barometer for the wider debates over cultural authenticity, ownership, and theft that all performers (both Jewish and non-Jewish) must navigate onscreen.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.