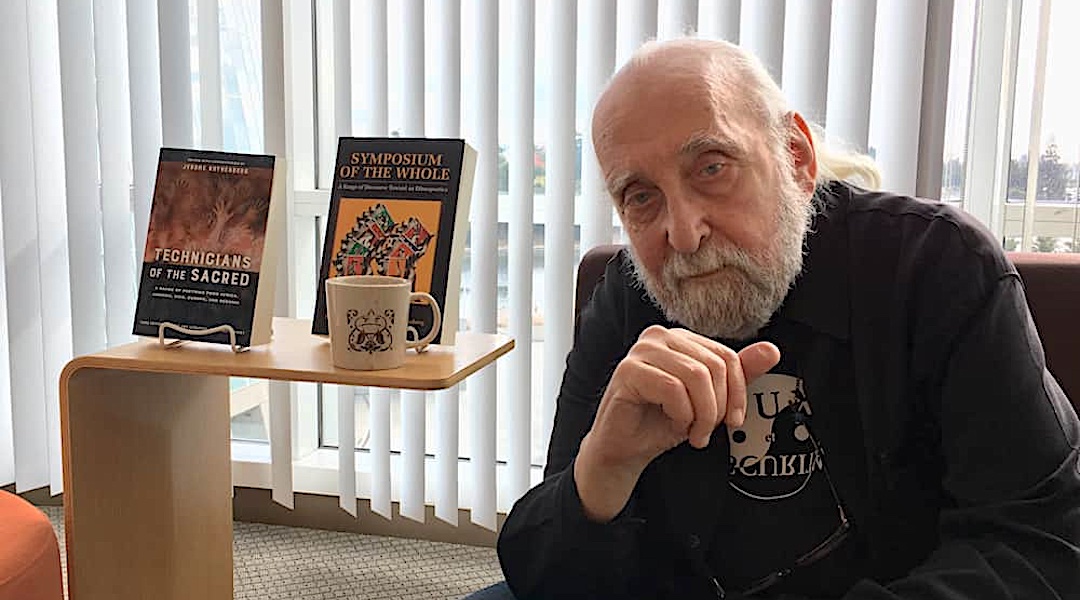

(JTA) — Jerome Rothenberg, an acclaimed, Bronx-born poet who inspired scholars and rock stars with his exploration of the poetry and oral traditions of peoples outside of the Western literary canon, died at his home in Encinitas, California on April 21. He was 92.

His son Matthew said the cause of death was congestive heart failure.

Rothenberg wrote and edited scores of poetry books, anthologies and pamphlets — including a number with Jewish themes — that have been translated into multiple languages. The poet was active until the end of his life. This spring he revised his libretto for an opera about Abraham Abulafia, the 13th-century Spanish kabbalist who traveled to Rome to convert the pope to Judaism. “Abulafia Visits the Pope” is scheduled to be performed May 25 at the University of California Irvine.

In June, Tzadik Records will release the album “In the Shadow of a Mad King,” featuring Rothenberg reading his poems on the Trump era with musical accompaniment by bassist Mark Dresser.

In the fall the last of his anthologies, “A Book of Americas,” will be published. A collaboration with Javier Taboada, it is focused on the poetry of North and South America.

“His work is luminous and it will be meaningful to people in future generations,” said Charlie Morrow, a composer in Helsinki, Finland who has collaborated with Rothenberg for 60 years. “I like to think that he’s come up with a big cookbook and that people will be making things from these recipes for a long time.”

Rothenberg had an enduring connection to the world of indigenous Americans. He recorded his chants of Navajo horse songs, which dealt with a mythical figure known as Enemy Slayer that goes to the sun and fetches magical horses, according to Navajo tradition. Rothenberg and his wife Diane, an anthropologist, lived among the Allegany Seneca Nation in western New York State over a period of several years in the 1960s and ’70s. “The experience has never left me,” Rothenberg told the San Diego Union-Tribune in a 2017 interview.

Rothenberg and his wife were honored by the Seneca clan in a Longhouse ceremony, according to a 2009 post by Diane Rothenberg on her husband’s blog, Poems and Poetics.

Marcia Abrams, an 83-year-old Seneca elder who lives in Steamburg, New York, said that members of the Allegany Seneca community were fond of the poet.

“Jerome came around here quite often,” she said. “He had a lot of friends here.”

Rothenberg’s groundbreaking anthology on ancient poetics, “Technicians of the Sacred,” came out in 1968 and jump-started a literary movement that came to be known as ethnopoetics. A third edition was published on its 50th anniversary in 2018 and the book is still in print more than a half-century after its initial publication.

“The breakthrough insight of ‘Technicians of the Sacred” was that poetry could be drawn from ritualistic experiences, chants, incantations, and shamanic visions that originated in Africa, Asia, Oceania, or within Native American groups,” wrote Jake Marmer, poetry critic of Tablet.

“Technicians” influenced a number of rockers. Jim Morrison of The Doors was said to have been so moved by the book that he was buried with it. Warren Zevon was also a fan.

“I kept ‘Technicians of the Sacred’ by my side for years. It completely turned around the way I wrote poetry,” said Nick Cave, the Australian front man for the rock band The Bad Seeds. “Jerry’s poetry and his anthologies completely opened me up to a whole different way of understanding poetry.”

Eugene Hütz, the lead singer of the New York punk rock group Gogol Bordello, said “Technicians” was his “road bible” for a couple of years while he was touring.

“I was bewitched by that book,” he told JTA.

Bob Holman, founder of the Bowery Poetry Club and a longtime friend of the poet, used the book as the only text for a course on endangered language poetry he taught at Columbia University. Rothenberg was a “one-man band” when it came to bringing oral traditions and ancient poetics into the avant-garde, Holman said.

“The reason why it’s so hard to study the oral traditions is because they’re not written down,” said Holman. “But Jerry wrote them down.”

Jerome Rothenberg was born to Polish Jewish immigrants. He grew up in the Bronx where Yiddish was his first language. His grandfather was a devotee of the Radzymyn rebbe, the leader of a Polish Hasidic dynasty. The family claimed descent from Meir of Rothenburg, a revered 13th-century rabbi from what is now Germany.

A graduate of the City College of New York, Rothenberg served in the U.S. Army in Mainz, Germany from 1953 until 1955. He began his literary career in the late 1950s as a translator.

Visitors to Rothenberg’s home in the San Diego suburb of Encinitas couldn’t help but notice an old Jewish tombstone that Morrow said leans against a garage wall. Inside the house, Rothenberg displayed a Torah cover on the wall along with indigenous masks and artwork.

Rothenberg explored aspects of his Jewish identity in the books “Poland/1931” and “A Big Jewish Book.”

“Poland/1931” consists of a series of poems he started writing in the 1960s. Rothenberg described the collection as a search for his roots in “a world of Jewish mystics, thieves and madmen.” In a conversation at a Los Angeles art exhibition last October Rothenberg said that when he felt the Holocaust coming into his poetry, he initially resisted it but decided to go to Poland in the 1980s “and began to face — or hear — the voices of the dead: dybbuks, dybbukim, those who died before their time.”

“A Big Jewish Book” is a 600-page collection of verse translated from several languages, including Hebrew, Aramaic, Yiddish, Ladino Arabic and Persian. Its pages are filled with the liturgical poems known as piyyutim, kabbalah from the oral tradition, excerpts from holy texts and work from poets through the ages. Rothenberg included Bob Dylan’s liner notes for the “Highway 61 Revisited” album and his own poem, “The Murder Inc. Sutra,” which references Jewish gangsters of the early 20th century:

Jewish bandits

beautiful men of noses enlarged with purple veins

or still-curled earlocks from childhood

who dared to cross the border in three coats

watchbands laid out from wrist to shoulders

but beardless could whistle

lost messages in secret Jewish code

Rothenberg was an emeritus professor of visual arts and literature at the University of California San Diego, where he was a tenured professor beginning in 1989.

In addition to his wife Diane, Rothenberg is survived by a son, Matthew.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.