(JTA) — I am the only Jewish elected official in Rochester, the third-biggest city in New York State. I am 38 years old, which when it comes to Israel can feel like the political “sandwich generation” — old enough to know that Israel was once seen as vulnerable, and young enough to understand that many cannot remember an Israel before Benjamin Netanyahu. The generational differences can feel massive at times, including at this moment when communities like Rochester are struggling to define and explain antisemitism.

Rochester has a Jewish community of roughly 20,000, with strong, well-resourced institutions. Antisemitism lurks here like it does in many American cities. When an incident occurs, like swastika graffiti appearing in a Jewish cemetery, the Jewish Federation of Greater Rochester typically takes the lead to publicly call out antisemitism and mobilize the community. The federation carved out a niche as the leading Jewish institution in the fight against antisemitism, even starting a Center to End Hate that strives to “unite the community in overcoming hate through education, dialogue and positive action.”

But in recent years — and more acutely in recent weeks — the federation has not kept up with the changing political landscape affecting discussions and definitions of antisemitism.

In 2019, the Monroe County Republican Party sent out advertisements in support of their candidate for district attorney that included familiar antisemitic dog whistles. The ads depicted George Soros as the “globalist” pulling the strings of the Democratic nominee because he wanted to “buy this election to install a far-left puppet.”

I shared my anger and concern about this advertisement with the federation and Center to End Hate leadership. They promised to have private conversations with the GOP leadership, although if they did they never reported back to me. I co-wrote an oped about the subject with a local rabbi and attorney and asked the federation if they wanted to join. They declined. The GOP never apologized, and the federation never publicly uttered a word about this antisemitism.

Last month the Rochester City Council, like so many other cities across the country, considered a symbolic ceasefire resolution. I was reluctant to welcome international politics into City Hall. When it became clear that a majority of the council wanted to pass a resolution, I decided to get involved in crafting the language to help ensure it did not include antisemitic language I had seen in other resolutions.

I vetted resolution language with Jewish lay and religious leadership, academics and Israelis. I sought to avoid some of the specific language that has proven so divisive in the discourse about Israel, like apartheid and genocide, and focus narrowly on the goal of a ceasefire. I discussed the language with the federation multiple times to get feedback. I did not expect the federation to be supportive, but I was surprised to learn that they found the idea of a resolution antisemitic regardless of the language.

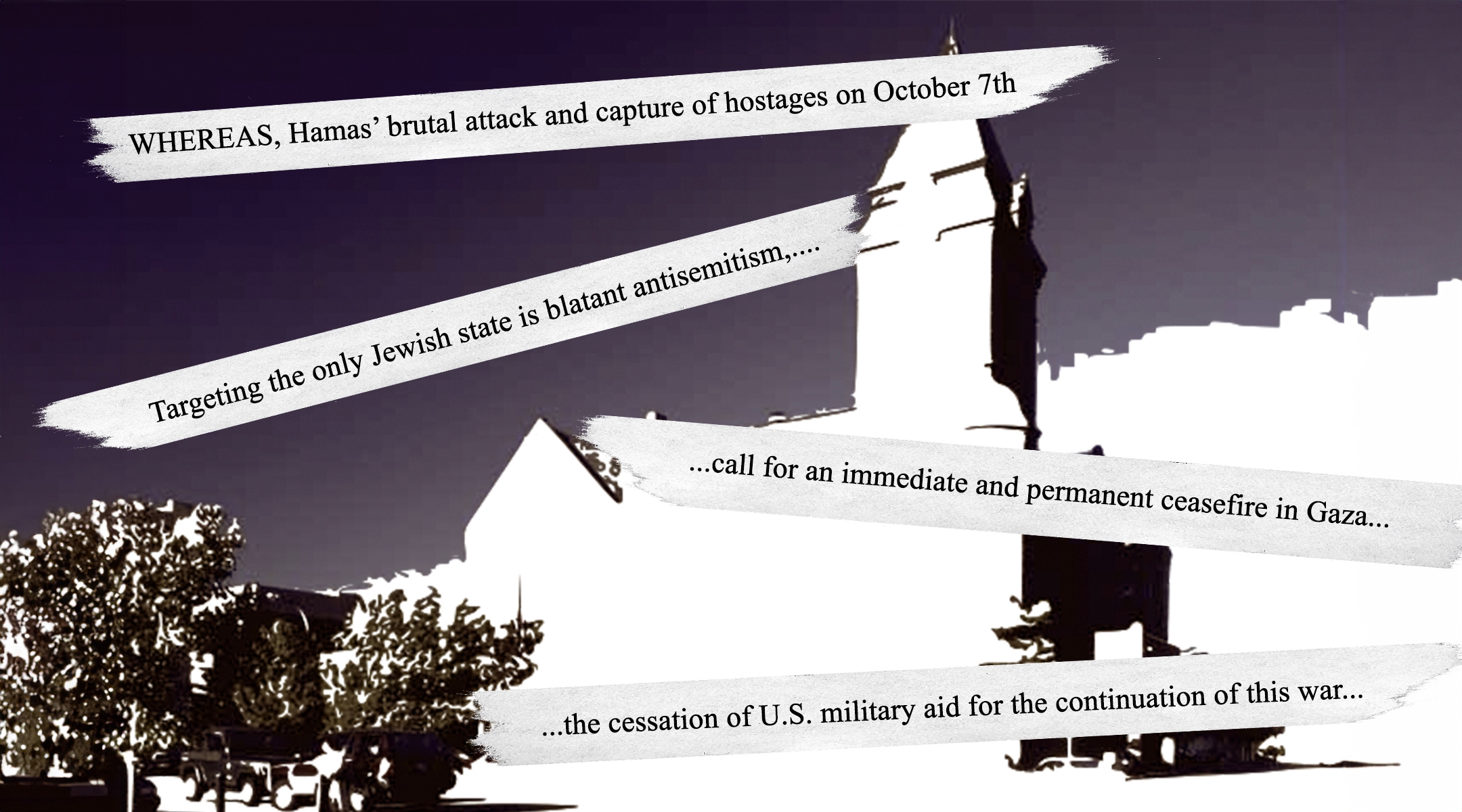

The federation chose to rally against the idea of a resolution. Leadership sent talking points directly from the Jewish Federations of North America to members of the Jewish community here. These talking points, written far away from Rochester, stated: “the proposed resolutions City Council is being asked to consider are antisemitic at their core. The resolutions demonize, delegitimize and apply a double standard to Israel – the ‘three Ds of antisemitism.’ If these resolutions are adopted, City Council will be empowering terrorist sympathizers and Jew haters.”

I found the “three D’s” — a formulation popularized by former dissident Natan Sharansky — to be an odd choice for a definition because it has rarely been cited in the last few months of very public, national discourse about antisemitism. But even by those standards the proposed resolution was not antisemitic. To many supporters of a ceasefire, it is not a double standard to ask Congress to stop shipping weapons to Israel while Gaza is facing imminent famine and a chronic shortage of medical supplies. I trust that my colleagues would demand the same of any country that was supplied with billions of dollars of armaments from the United States while civilians experienced dire humanitarian crises like famine.

Council members received hundreds of comments echoing the federation’s talking points and accusing the entire City Council of antisemitism for even considering the resolution. We also received hundreds of comments in favor of a ceasefire resolution, with many commenters citing their Jewish identity and values as reasons for support. (Ultimately, the council approved two non-binding resolutions, including one written and co-sponsored by me.)

We held a public meeting with so many speakers that it lasted over five hours. The meeting affirmed the challenges of being a leader in the sandwich generation. I watched as different generations spoke past each other with anger and sadness in their voice. It reminded me of Peter Beinart’s essay in the New York Times about the “great rupture in American Jewish life,” when he wrote, “For many American Jews, it is painful to watch their children’s or grandchildren’s generation question Zionism … It is tempting to attribute all of this to antisemitism, even if that requires defining many young American Jews as antisemites themselves.”

The division in Rochester’s Jewish community is happening as we speak. It’s painful to experience. It must be confusing for our non-Jewish neighbors, who are left wondering what is or is not antisemitism. And the well-organized institution that once served as a leading voice has squandered credibility to arbitrate antisemitism.

I share these stories about the federation’s challenges because I suspect they are symptomatic of problems that other Jewish communities are facing today. If Jewish communities cannot properly diagnose antisemitism, then we cannot propose real solutions. And if leading Jewish institutions like federations cannot effectively identify antisemitism, how can we expect policymakers, community members, and activist groups to help us combat it?

This question is central to how we relate to the world around us, and how we understand each other within our own community. We in the sandwich generation have work to do.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.