(New York Jewish Week) — My son is in town from California for Passover, and on Tuesday night he treated the rest of the family to a Mets game.

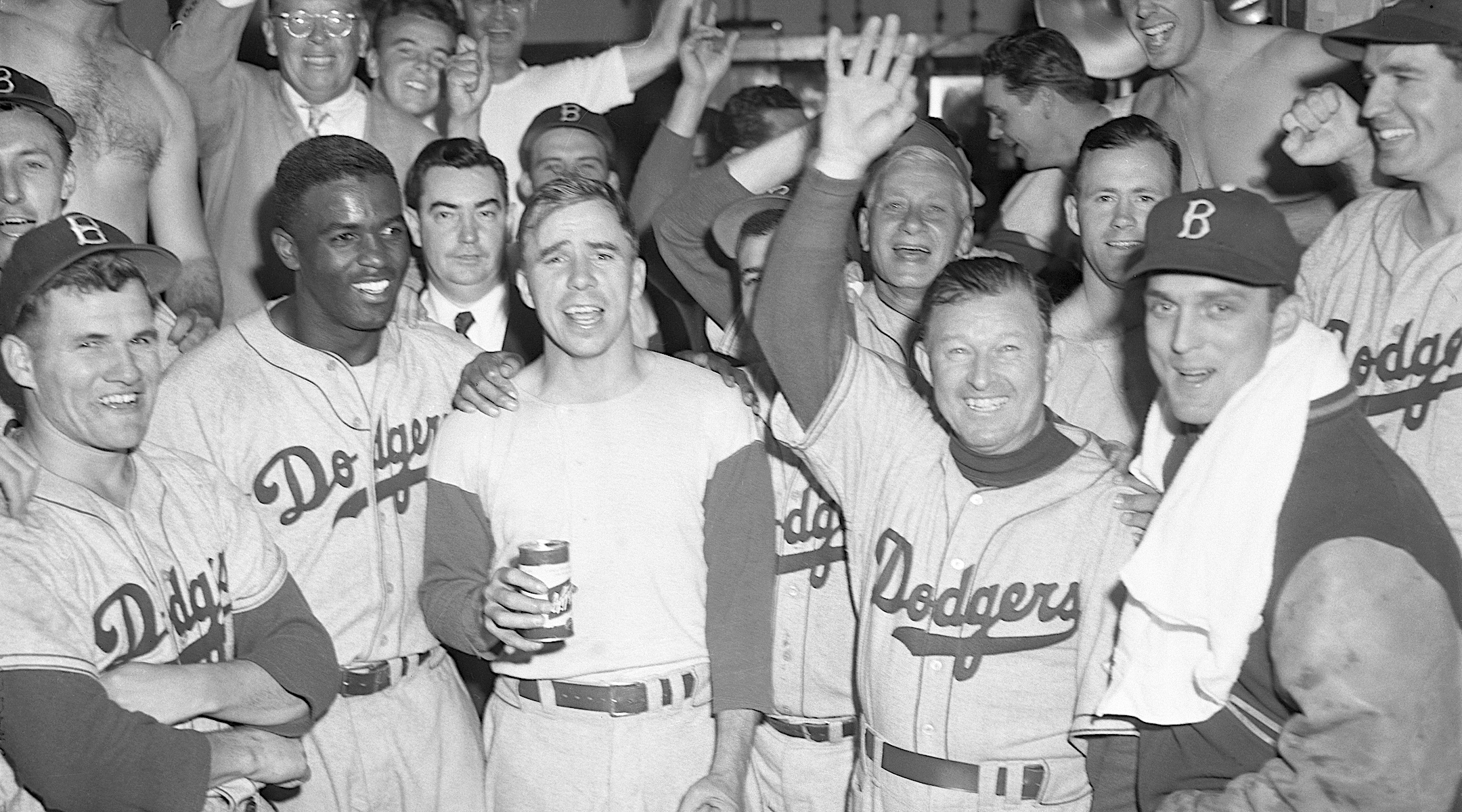

Before the first pitch, the Mets had a moment of silence for the pitcher Carl Erskine, who died that day at age 97. Erskine was a star of the storied Brooklyn Dodgers teams of the late 1940s and ’50s, when they won the National League pennant five times and the 1955 World Series.

Erskine was also the last surviving Dodger to have been profiled in Roger Kahn’s classic 1972 book “The Boys of Summer,” a celebration of a team that included Jackie Robinson — the first player to break the major leagues’ shameful color line — and future Hall of Famers Roy Campanella, Duke Snider and Pee Wee Reese. (Sandy Koufax was a rookie on the 1955 team, but only came into his own after the team moved to Los Angeles in 1957.)

Erskine’s death seemed to close a storied chapter in New York and, dare I say it, Jewish history. The Dodgers ruled the National League when the Jews ruled — or at least left an indelible cultural stamp on — Brooklyn. In 1950, one out of four Brooklynites — 561,000 — was Jewish. And often the fate of the team — scrappy strivers who rose from adversity — seemed to mirror the fate of the Jews themselves.

“Arguably, no baseball team ever forged a closer relationship with Jewish fans than did the Dodgers during their Brooklyn years,” Bill Simon, co-editor of “The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture,” wrote in 2022. “In other New York City boroughs, the Yankees and Giants had their Jewish adherents, as did Major League Baseball teams in other cities, but in Brooklyn the Dodgers drilled deep into the social fabric.”

Kahn captures that connection in his book, which includes his own memories of growing up Jewish in Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza section, the son of two teachers. Even mediocre Dodgers teams provided a distraction from conversations about “the Nazi-Soviet treaty, nervousness about the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and horror at Hitler’s pogroms.”

Philip Roth celebrated the team in “Portnoy’s Complaint,” when his Jewish protagonist fantasizes about playing center field for the Dodgers, “standing without a care in the world in the sunshine, like my king of kings, the Lord my God, The Duke Himself (Snider, Doctor, the name may come up again), standing there as loose and as easy, as happy as I will ever be, just waiting by myself under a high fly ball…”

Kahn describes an era in Brooklyn that began after World War II, when what had been a “heterogenous, dominantly middle-class community, with remarkable schools, good libraries and … major league baseball” was about to be riven by racial tension in the streets and white flight to the suburbs.

But with Robinson, Jews saw an avatar for their own acceptance in white society.

“It really delighted people, particularly Jewish Americans, that Jackie Robinson was on this team,” the novelist and historian Kevin Baker, author of the new book “The New York Game: Baseball and the Rise of a New City,” told me Thursday. “It seemed like another affirmation that this was going to be a fairer country, a country where they could get a fair shake.”

I reached Baker at Citi Field, the Mets’ home in Queens, shortly before an afternoon game against the Pittsburgh Pirates. In his book, the first of a projected two volumes, he punctures the myth that baseball is a “pastoral” game born in rural America, and writes that its real roots are in the streets of New York.

And as a city game, baseball reflected the ethnic diversity of those streets. “Starting in the 1930s, ethnic America, and particularly Jewish and Catholic America, were recognized as full Americans in politics, in the movies, in sports,” said Baker. “And Brooklyn was always kind of a cliche of that.”

That recognition didn’t extend to African Americans, but in the pre-Civil Rights era, Brooklynites could nonetheless imagine, thanks to Robinson, a more tolerant future. While players, umpires and journalists elsewhere were still viciously racist, Kahn writes, the Dodgers “stood together in purpose and for the most part in camaraderie… That spirit leaped from the field into the surrounding two-tiered grandstand. A man felt it; it became part of him, quite painlessly.”

One of those men was Erskine, a devout Christian from Indiana, who years after he retired wrote a book, “What I Learned From Jackie Robinson.” “Jackie made people look beyond race, inside their own souls, inside the depths that made them human, and see the light,” he wrote. Erskine, whose youngest son was born with Down syndrome, also credited Robinson with helping change perceptions about people with disabilities.

Erskine never played for the Mets, but the team has always seen itself as the spiritual heirs to the Dodgers: the working-class foils to the blue blood Yankees (even as, Baker pointed out, the Yankees tended to recruit more players of color than the Mets starting in the 1970s). Citi Field even took its design cues from Ebbets Field, the old Flatbush home of the Dodgers.

I’ve tried to explain this to my son, who wonders why Citi Field’s main entrance is named for Robinson when he never wore a Mets uniform (as far as I am concerned, every Major League stadium should have a Jackie Robinson Rotunda). I also explain how my mother, born and raised in Queens, was a die-hard Dodgers fan until they decamped to California, and embraced the Mets when they played their first dismal season in 1962. I’ll never forget her joy when the Mets sealed their first World Series in 1969.

I was shocked to realize that Kahn, who was 92 when he died in 2020, interviewed the Dodger greats less than 20 years after they retired, when they were only in their late 40s and early 50s. The book looks back on their era as if from a different century, not just two decades. But so much had changed that it might as well have been another century: Martin Luther King was dead. The Vietnam War was raging. Brooklyn’s “Jewish” neighborhoods were less so (this was years before gentrification, the mass immigration of Soviet Jews and the explosive growth of the haredi Orthodox community).

As a result, Kahn’s book is not only nostalgic, but elegiac. In writing about an aging baseball player, he might as well have been writing about a way of life: “As his major league career is ending, all things will end. However high he sprang, he was always earthbound. Mortality embraces him. The golden age has passed as in a moment. So will all things. So will all moments. Memento Mori.”

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.