(New York Jewish Week) — When downtown steakhouse Delmonico’s opened in 1827, it was the first fine dining restaurant in New York City. Famous for its eponymous ribeye steak and Lobster Newburg, Delmonico’s boasted high-profile customers like Abraham Lincoln and Mark Twain.

Among them, however, were few Jews. Though New York was home to some 40,000 Jews by the eve of the Civil War, most of them were Spanish, Portuguese or German-speaking immigrants — or their descendants — who strictly adhered to Jewish law. These Jewish New Yorkers kept kosher and therefore primarily ate at home, or at the homes of fellow Jews. Even those who had prospered by the mid-1800s and established themselves in American society couldn’t, in good conscience, enjoy high-end restaurant fare.

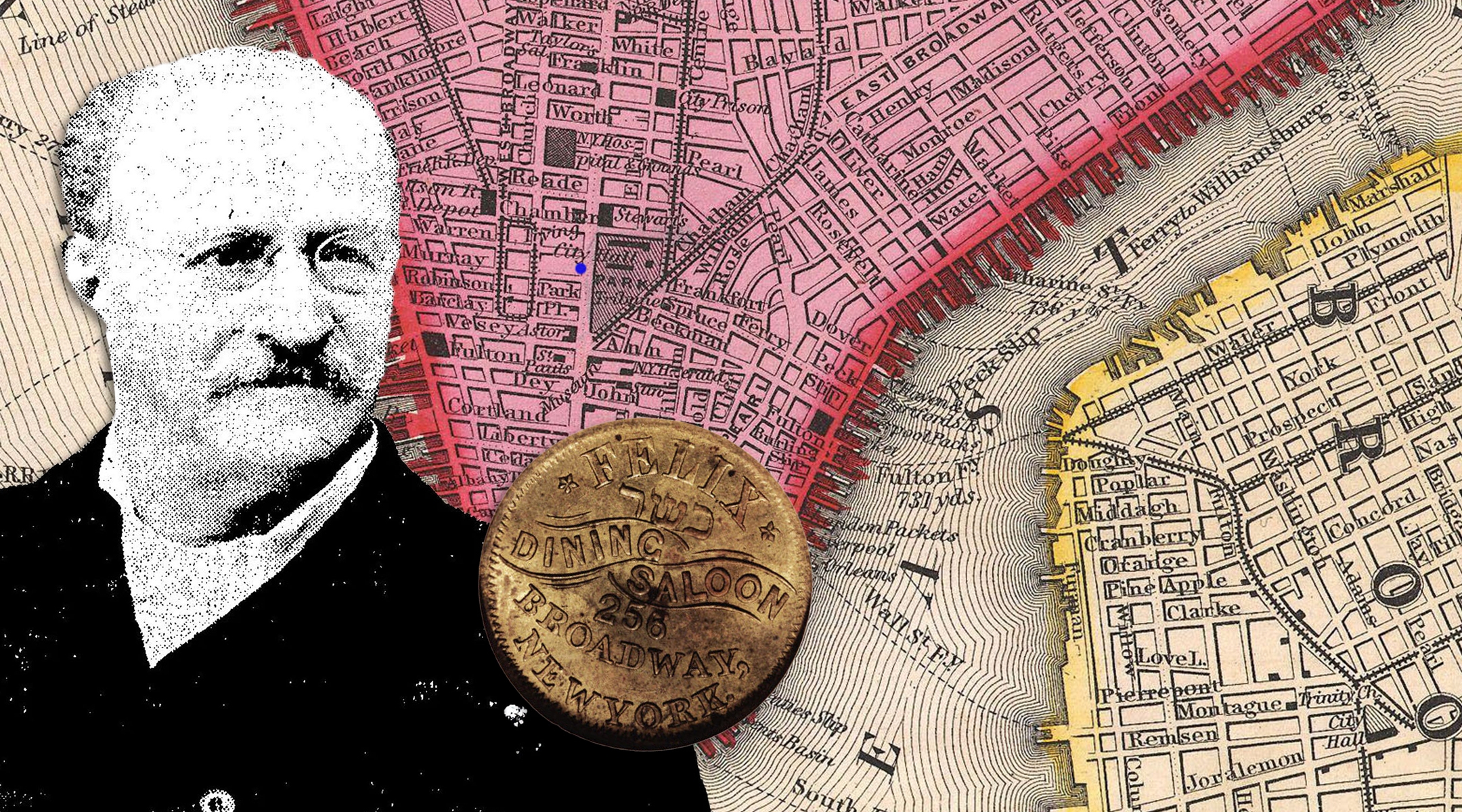

That is, until an enterprising Jewish Frenchman named Felix Marx arrived on these shores. Born in Alsace, France, in 1825, Marx landed in New York in 1858. Having worked as a kosher butcher before immigrating, Marx set out to create a Delmonico’s-style offering for well-to-do, observant Jews. Within two years, he opened his first establishment opposite City Hall Park. The restaurant was called Felix’s Dining Saloon — though, colloquially, it was often referred to as “The Kosher Delmonico,” serving kosher haute cuisine to an elite clientele.

Today’s kosher diners have all manner of choices about where to eat in New York City, from hole-in-the-wall pizza shops to upscale vegan Mexican restaurants. But it wasn’t always that way — when Felix’s Dining Saloon opened, it was the first kosher restaurant in New York. There, Marx served as chef and his French-born wife, Julia Lisette, worked as cashier. By the mid-1860s, the restaurant moved nearby to a large, well-appointed space at 256 Broadway, between Warren and Murray Streets.

In addition to serving kosher food on the premises — in what he pretentiously deemed “the Felix style” — Marx announced in a June 1865 advertisement in The Jewish Messenger that his establishment was prepared to cater weddings and other parties at private residences, noting that he was also happy to furnish suppers “for the approaching ball season.”

During the Civil War, the restaurant did its patriotic part: When government-issued coins became scarce due to hoarding, Marx, like many thousands of business proprietors, stepped up to fill the void. In 1863, he arranged with a private mint to produce one-cent coins — widely accepted as substitutes for pennies — that advertised his restaurant. Unusually, however, Marx’s tokens bore a Hebrew word, “kosher,” as professor and historian Jonathan D. Sarna notes in “Jews and the Civil War.”

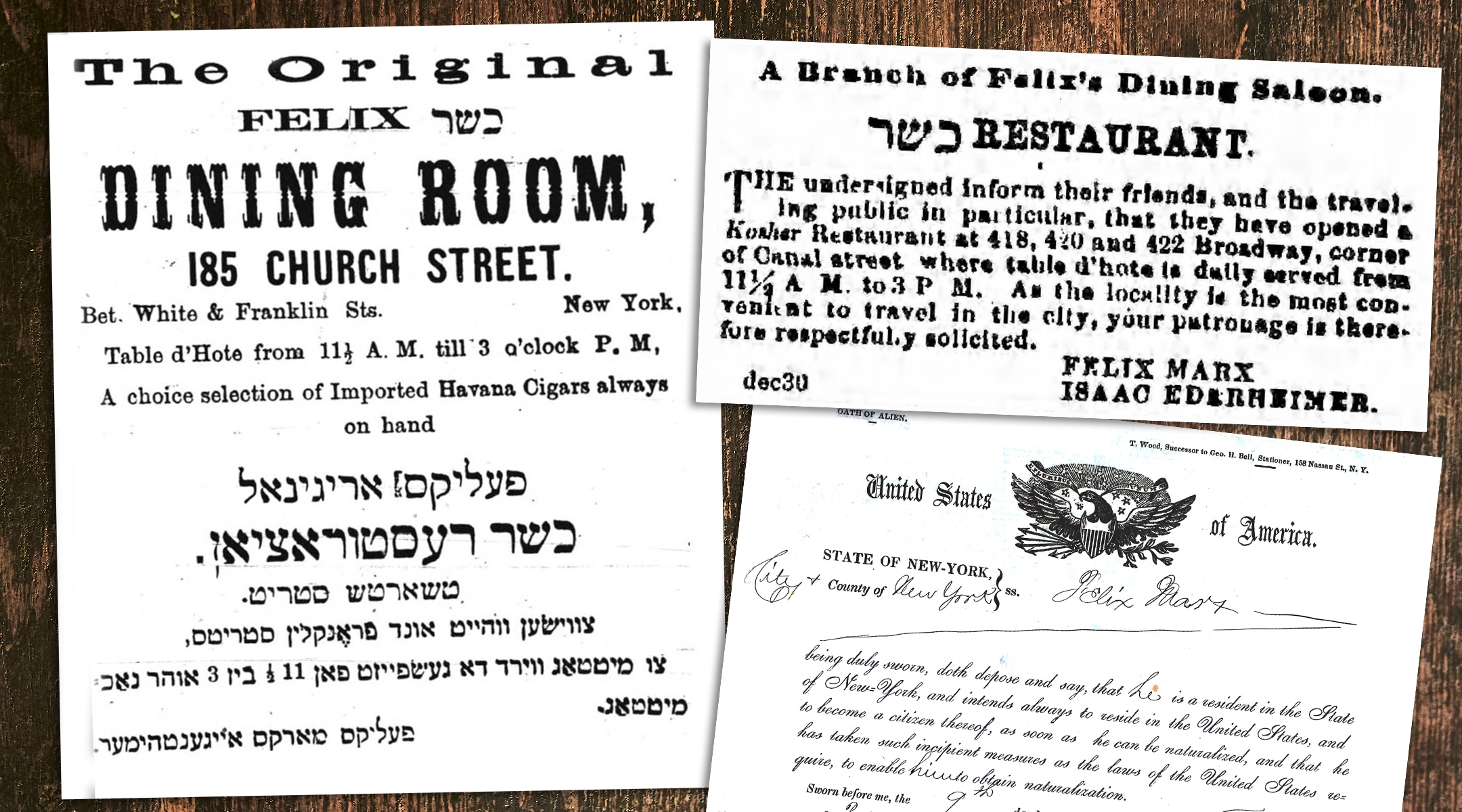

Two years later, in 1864, Marx added a second branch of Felix’s Dining Saloon up the street, at 418-422 Broadway. An advertisement in The Israelite that year proudly proclaimed — also in Hebrew — that it served only kosher fare.

Felix’s Dining Saloon was a fleishig, or meat, restaurant, which meant that, in accordance with Jewish law, there were no dairy products on the menu. That is, if Felix’s actually had a menu, or at least an à la carte one. The prix fixe restaurant served only lunch — from 11:30 a.m. to 3 p.m. — and a multicourse meal could be had for fifty cents (approximately $17 in today’s currency).

“It consists of several courses, barley or chicken soup, boiled beef or hamburger steak, with fried potatoes and sauerkraut, veal cutlet, roast duck or broiled chicken, with salad, and a compote of prunes and raisins or some delicate pastry,” the New York Sun wrote about the “German style” meal served by the restaurant. “A dish of the choicest fruit and a jar of celery stands always on the table. A cup of black coffee completes the meal.”

Before long, “the Felix,” as the place was affectionately known, ceased to be the only kosher game in town — and Marx, a hard-nosed businessman ever alert to competition, sometimes resorted to shenanigans to preserve his premier position. In 1873, a German Jew named Lazarus Blaut leased a space two blocks from the Felix for $300 a month with the intent of opening a rival kosher eatery there. In a lawsuit, however, Blaut alleged that Marx warned all the carpenters, masons and plumbers he had hired that he was a swindler who would not pay them for their work. (Ultimately, as the New York Herald reported, Marx succeeded only in postponing the opening of Blaut’s establishment by a few weeks.)

Some competitors, like Blaut, aspired to run restaurants on a par with the Felix, but most kosher restaurants were in another league entirely. “They are mostly small rooms in the cellars or upon the ground floors of tenements, furnished with a few wooden tables and chairs, with a bill of fare printed in Hebrew characters hanging outside the door,” the Buffalo Times reported in 1887. “In the windows the shrunken carcasses of geese are allowed to hang until blackened with exposure.”

Left: An English-Yiddish advert for the new incarnation of Felix’s Dining Room published in the May 11, 1877 edition of the Yiddishe Gazeten. Top right: An advertisement for Felix’s Dining Saloon that appeared in The Israelite on April 7, 1865. Bottom right: Marx declares his intention to naturalize on Feb. 9, 1872. (Design by Mollie Suss)

Those eateries, where “the service is filthy and the food is scarcely fit to eat,” were generally run by poor Russian and Eastern European Jews, who began to arrive in large numbers in the early 1880s. A New York Sun reporter who ventured into one such basement eatery on a Jewish holiday found 15 men, all in shirtsleeves and many wearing their hats, seated at a long table. “The gutturals of the jargon” — by which he meant Yiddish — “were almost as noisy as the clatter of dishes and the rattle of knives and forks.” The fifteen-cent meal (just over $5 in today’s currency) consisted of soup, boiled meat, stew, boiled potatoes and coffee. He noted the presence of a “fairly clean” tablecloth, but speculated that had it not been a holiday, the tabletop would likely have been bare.

Compare that to the clientele and the atmosphere of the Felix. There, a selection of “Havana seegars” was always on hand, and “The men are well-dressed and almost without exception well-groomed,” the Sun reported. Among the regulars were Joseph Wechsler, one of the co-founders of what became the department store Abraham & Strauss. Politician and philanthropist Randolph Guggenheimer — attorney, school commissioner and the inaugural President of the Council of the City of Greater New York —was another, as was French-born Ferdinand Levy, first coroner and later city register of the local government. Even the great Jacob Schiff, the international banker and philanthropist famous for his role in financing the expansion of America’s railroads, was often seen at the Felix.

The clientele was not entirely Jewish. “The excellence of the cooking and the peculiar features of the place” attracted many non-Jews, too. As The Sun reported in 1891, “it has become quite a resort for merchants of every class whose business is in the vicinity of the restaurant.”

These patrons didn’t just come for the cooking; there was also a perception of quality. Since kosher meat was slaughtered locally, many non-Jews believed it was fresher and more nutritious than meat from cattle killed in the Midwest days earlier and brought to New York by train. At the turn of the century, The Sun estimated that somewhere between an eighth and a quarter of the Felix’s diners were non-Jews.

As the years passed, Marx opened and shut branches, partners came and went, and Marx gave up the business, only to resume it later. In 1874, two years after his naturalization, he announced his intention to retire and return to Europe and put his business up for sale. In the advertisement, he offered the purchaser an opportunity to learn the business along with a pledge that he’d never open a competing dining establishment in New York.

He soon reversed course: In 1876 came an announcement published in The Messenger that “the original Felix” was back and would be re-opening at 185 Church Street.

Exactly how kosher was the Felix? The 1880s were a time of rampant corruption in the local kosher meat industry. Because profits were considerably higher if one passed off non-kosher meat as kosher, there were strong incentives for supervisors, slaughterers and butchers to play fast and loose with the rules. But it’s hard to imagine that Marx would knowingly have dealt with dishonest dealers; it would have been folly to risk his reputation on counterfeit meat for a few pennies.

Ironically, the one recorded criticism of the restaurant’s fidelity to the dietary laws came in 1893 after Felix had sold the business to his son Ernst and retired for good. The source was one Yudel Mannecker, a man skilled in plucking forbidden fats and veins from meat — an important step in the process of rendering food kosher. Ernst had brought Mannecker to New York from Kiev to work in the kitchen and paid him a whopping $40 per week, roughly four times the wage of a typical Lower East Side laborer. When Mannecker was let go for incompetence, however, he sued the restaurant and complained he had been forced to work on the sabbath. A New York Sun piece from early 1893 quoted Ernst as insisting that there was no need for his services because the restaurant’s customers didn’t know kosher from unkosher food.

Before long there was bad blood between father and son. Business declined, and Ernst Marx couldn’t make the payments. Felix Marx secured a judgment against him for just over $14,000. He later disinherited the young man, castigating Ernst in his will for “unfilial conduct.”

In 1897, after the death of his wife, Marx moved to Washington Square. He continued to dine at the Felix, however, often with a lifelong friend, an Alsace-born butcher named David Metzger. Both had amassed fortunes in the neighborhood of a million dollars. On Sept. 21, 1903, the two had agreed to meet at the restaurant, but Marx never arrived; he had died early that morning. Metzger himself collapsed the same day, and a few days later the friends were buried side by side at Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Felix’s Dining Saloon’s fame spread far and wide and was “not confined to this tight little island,” as the Jewish Exponent reported in 1903. “For fifty years it has been frequented by large numbers who found the dietary laws under such conditions no barrier to their appetite.” In its last location, at 193 Mercer Street, it appeared in the New York City directory until 1912 — marking a half-century run that’s impressive for any New York eatery.

Scott D. Seligman is a national award-winning author whose newest book, “The Chief Rabbi’s Funeral: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Antisemitic Riot,” is due out in November.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.