(JTA) — The war between Israel and Hamas — now in its seventh month — shows no sign of ending soon.

The United States said Monday that Hamas rejected the most recent proposal for a temporary ceasefire in Gaza. Meanwhile, an unprecedented rocket attack on Israel from Iran scrambled the calculations of Israel and its allies. In a rare statement, the Israeli Mossad intelligence service said Hamas “continues to take advantage of tensions with Iran to try to unite the theaters and to achieve a general escalation in the region.”

But Israel said April 7 that it was withdrawing all but one brigade from southern Gaza, and its special ground forces had “concluded its mission” in the city of Khan Younis and left Gaza “to recuperate and prepare for future operations.”

While Israel still insists it must invade Rafah to finish off Hamas, this month’s withdrawal raises the possibility for an end to the war itself – or at least an opportunity for experts in the region to begin asking what ending the war would look like, and what happens next.

The short answer, they say? Nothing good.

After Hamas’ brutal attack on southern Israel on Oct. 7, the Israeli government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced two main goals: eliminating Hamas and bringing back the hostages taken by its terrorists to Gaza.

Israel has seriously degraded Hamas’ military and killed one of its top commanders, Saleh Arouri, allowing Israel the potential to declare at least a partial battlefield victory. Should hostages be returned and the bodies of the missing accounted for — for now, a big if — that would bring Israel closer to its stated goals.

But then what? Gaza is a shambles, and in the absence of Hamas — which has governed the enclave in various ways since 2006 — someone else has to coordinate its reconstruction and deliver on the everyday needs of a traumatized and, in large part, internally displaced population of more than 2 million.

Meanwhile, Israel will need assurances that its own people are safe from attacks, and that a rump force of Hamas or whichever radicalized fighters now emerge won’t stage another Oct. 7, or even a series of smaller attacks.

Experts suggest a limited range of possibilities for the future governance of Gaza:

- The Palestinian Authority, which cooperates with Israel in governing Palestinian population centers in the West Bank, could do the same in a postwar Gaza.

- A United Nations-led or international coalition could keep the peace and deliver humanitarian aid.

- A group of countries in the region could take charge — including Egypt, Saudi Arabia and nations that have signed normalization agreements with Israel.

None of these options will be easy, or even likely.

“I would say that numbers two and three are basically kind of fading. So we’re back to number one,” said Nathan Brown, a professor of political science and international affairs at George Washington University. “The P.A. is now kind of making noises to suggest it might play some kind of role if given that appropriate fig leaf.”

The two main obstacles to a P.A. role in Gaza’s future are the Israeli government and the Palestinian people themselves. The Israeli government — led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu — deeply distrusts the P.A., sees it as weak and accuses it of inciting and incentivizing violence against Israelis. Netanyahu is also opposed to a Palestinian state, and giving the P.A. control of areas in the West Bank and Gaza could pave the way toward statehood.

Palestinians don’t like the P.A. much better: Polls show that they see it as inept, and that they have an even dimmer view of its longtime president, Mahmoud Abbas. He has not stood for election in nearly two decades, and the vast majority of Palestinians want him to resign.

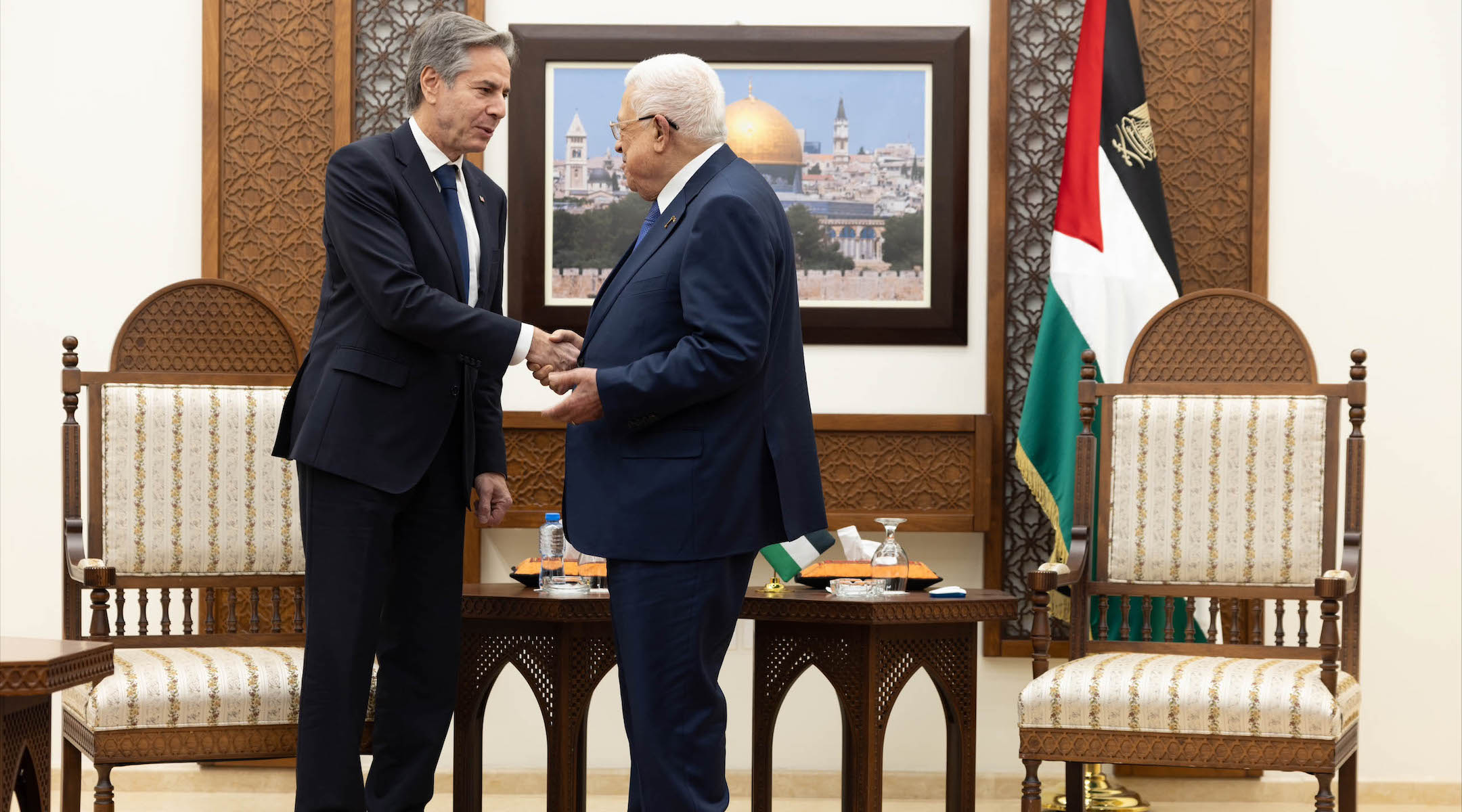

Secretary Antony J. Blinken meets with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas in Ramallah, West Bank, Jan. 10, 2024. (Official State Department photo by Chuck Kennedy)

“For the P.A. to take on a significant role it would be seen by most Palestinians as essentially a collaboration with the Israelis,” said Brown, the author of six books on politics in the Arab world, including “Palestinian Politics After the Oslo Accords” and “When Victory Is Not an Option: Islamist Movements in Arab Politics.”

“So maybe you could have some kind of low-level Palestinian Authority presence there, but I don’t think the P.A. could assert itself that way,” he said. “It would require really active not just Israeli acquiescence, but really active Israeli support, and I can’t imagine this government doing it.”

And even if Israel and the P.A. could agree to an arrangement in Gaza, the task is enormous: “This isn’t just sort of stepping into an existing administration,” said Brown. “This is really like stepping into a massive refugee camp with none of those services provided.”

Meanwhile Israel’s far right has its own plans for the future of Gaza: Jewish resettlement. In January, right-wing ministers and lawmakers met in Jerusalem to discuss rebuilding Israeli settlements in Gaza, which Israel dismantled in 2005. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and other senior officials have repeatedly said they have no intention of reoccupying Gaza, and most Israelis oppose the idea. But far-right leaders hold senior positions in Netanyahu’s coalition and can play the spoiler in implementing any of the alternatives.

Netanyahu has also proposed an alternative to resettlement or a strong role for the P.A.: He suggested putting “civil administration and responsibility for the public order” in the hands of “locals with administrative experience.”

“There’s been this idea of finding heads of clans or tribal chiefs or business people with some sort of authority who can set up alternative structures,” said Michael Koplow, the chief policy officer of Israel Policy Forum, a U.S.-based group that supports Palestinian statehood alongside Israel. “The idea is that you then run Gaza in a more localized way instead of treating it as a whole, and you find the strong man or committee of strong men who can run each municipality. I think that’s unlikely and unworkable for all sorts of reasons,” including the likelihood that local leaders will be intimidated by what remains of Hamas or their sympathizers.

“What does seem clear, however, is that both sides now have no good options that will bring lasting peace or stability,” said Koplow, reflecting not just the views of his organization, which has long supported a two-state solution, but a growing consensus across an ideological spectrum.

Writing for the right-leaning Israeli think tank BESA, Shai Shabtai described victory as a “fundamental weakening of the enemy’s military capacity to do harm.” In the aftermath, he envisions a years’-long process in which the Israeli Defense Forces would continue to battle and eliminate guerrillas and a local civilian authority would emerge, responsible for governance and law enforcement.

“Such a process does not yet appear practical or feasible in Gaza, and even if it were, it is highly complex,” Shabtai acknowledged. And even if were to come about, it would be temporary absent “a fundamental change in the situation on the ground.”

In an interview, Dana Stroul, director of research and senior fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, described the immediate challenges following a military victory.

“We’re going to have to have discussions about clearing the rubble, getting people back to their homes,” she said. “Kids are going to have to go to school, people are going to need medical care and need to get water pumps and sanitation back on. All of that requires some sort of governing entity. You want a phone number you can call, an office you can go to, and if it’s not going to be Israel in charge — and they’ve said they don’t want to be an occupying force — it has to be something else. And there is no articulated answer from either Netanyahu or anybody else about what that day after looks like.”

An Israeli battle tank is deployed to guard a position as displaced Palestinians flee from Khan Yunis in the southern Gaza Strip on Jan. 30, 2024. (Mahmud Hams/AFP via Getty Images)

Like others, Stroul, who from 2021-2023 served as U.S. deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East, knows what a day after can look like when things go horribly wrong.

“We know, from decades of U.S. military experience in Iraq and Afghanistan, that if you just have military operations to defeat the enemy, and you don’t actually think about the needs of the civilian population, then you are creating conditions for perpetual insecurity,” said Stroul.

Brown compared the challenges facing Israel and the Palestinians to the “de-Ba’athification” process after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

“Conventional military victory was obtained easily within weeks, but as soon as they got to Baghdad the first thing they did was essentially abolish large parts of the Iraqi state,” said Brown. “They abolished the Ba’ath party, abolished the Iraqi military, sent everybody home, and then hoped something else would emerge. It did not, and I think that’s really been informing an awful lot of the heavy American pressure [on Israel] on the day after.”

Koplow said that even if Israel succeeds in removing Hamas from government and defeating their military, there will be a sizable number of people who worked in Hamas’ bureaucracy in various functions in Gaza since 2007, after a power struggle with the P.A.-affiliated Fatah left Hamas in control of the strip.

“I think that ultimately unless this is going to be a forever war, Israel is going to have to deal with the non-military Hamas institutions in some way, shape or form that doesn’t mean accepting them and allowing them to rule Gaza,” said Koplow. “I think that not interacting with them is going to end up being a mistake.”

Koplow also believes the Iranian missile barrage may force Israel to choose between disregarding the P.A. and keeping Iranian influence at bay. “For all of its numerous faults, the PA is not an Iranian proxy,” Koplow tweeted on Saturday. “If the fight against Iran is going to be prioritized, it needs to mean changes with regard to Israeli policy in the West Bank and Gaza, full stop.”

But Israel is also a democracy, and on the day the war ends, it will have to deal with its own population — one that is deeply traumatized by Oct. 7 and angry with its government.

“The Israeli public now is traumatized, saying there is no one to talk to and they have no interest in Palestinian affairs,” said Shira Efron, senior director of policy research at the Israel Policy Forum. “At the moment the Israelis know what they don’t want to see,” which is a military threat from Gaza.

“And they want the hostages back, and they also don’t want a long term Israeli occupation of Gaza. They don’t want their taxpayers to pay for Gaza, or the education of its children. At the end of the day, the Israeli public would like Gaza to be managed in a responsible way.”

But Efron said a distinction needs to be made between what the people want and what is required of their government to lead and inspire them.

“We have to start thinking about how to solve and how to address what happens next. And it’s a difficult conversation that the Israeli public is not having at the moment,” she said.

At the moment it is hard to find any observer who feels optimism about what happens after the fighting stops. Even were Israel to encourage the P.A. to play a role in governing Gaza, the obstacles remain enormous, as Aaron David Miller, a former U.S. State Department Middle East analyst, wrote recently in Foreign Policy:

“Training thousands of Palestinian security forces would be a logical first step, but this will take up to a year or more,” he wrote. “Even if that were to happen, the P.A. has no credibility in the West Bank, let alone in Gaza. Elections for a new Palestinian Legislative Council and president are light years away. And given the P.A.’s weakness, it would need Hamas’s support in Gaza to return to govern.”

Miller tends to share the deep pessimism of Brown, who argued in a piece shortly after the start of the war that the region faces “a long twilight of disintegration and despair.”

“I think Israelis are looking at a future that is dark — not grinding on a daily basis, but just dark. It will leave a lot of people pessimistic about the society’s long-term future,” Brown told me this week. “And for Palestinians it is absolutely disastrous, and for the ones in Gaza, there’s just an enormous cost in human terms. For most Palestinians, they’ve got their national identity feelings, but they have no viable strategy for realizing national goals, and even their basic institutions are disintegrating.

“I’ve been kind of in a dark mood about this,” Brown continued, almost apologetically. “This destroying of tens of thousands of lives brought out the worst in almost all actors. I don’t see how anything good comes anytime soon.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.