(JTA) — Since the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the right to abortion is no longer protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. But that seismic constitutional change has triggered a new legal debate: In the absence of federal constitutional protection, does state law provide Jews with a religious liberty right to abortion? Last week an Indiana state appellate court answered yes to the question — invoking variations on the word “Jew” more than 70 times in the process.

As the first state appellate court answer to the question, the ruling presents a persuasive case for other state courts to follow, potentially opening the door for Jews — and others with similar religious commitments — to secure abortions that are motivated by religious values even where such abortions are otherwise prohibited by state law.

Now, with Arizona’s decision this week barring abortion after six weeks and with Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump saying that he would leave abortion decisions up to states rather than sign the federal ban that some on the right want, the significance of the ruling appears to have grown even since it was issued.

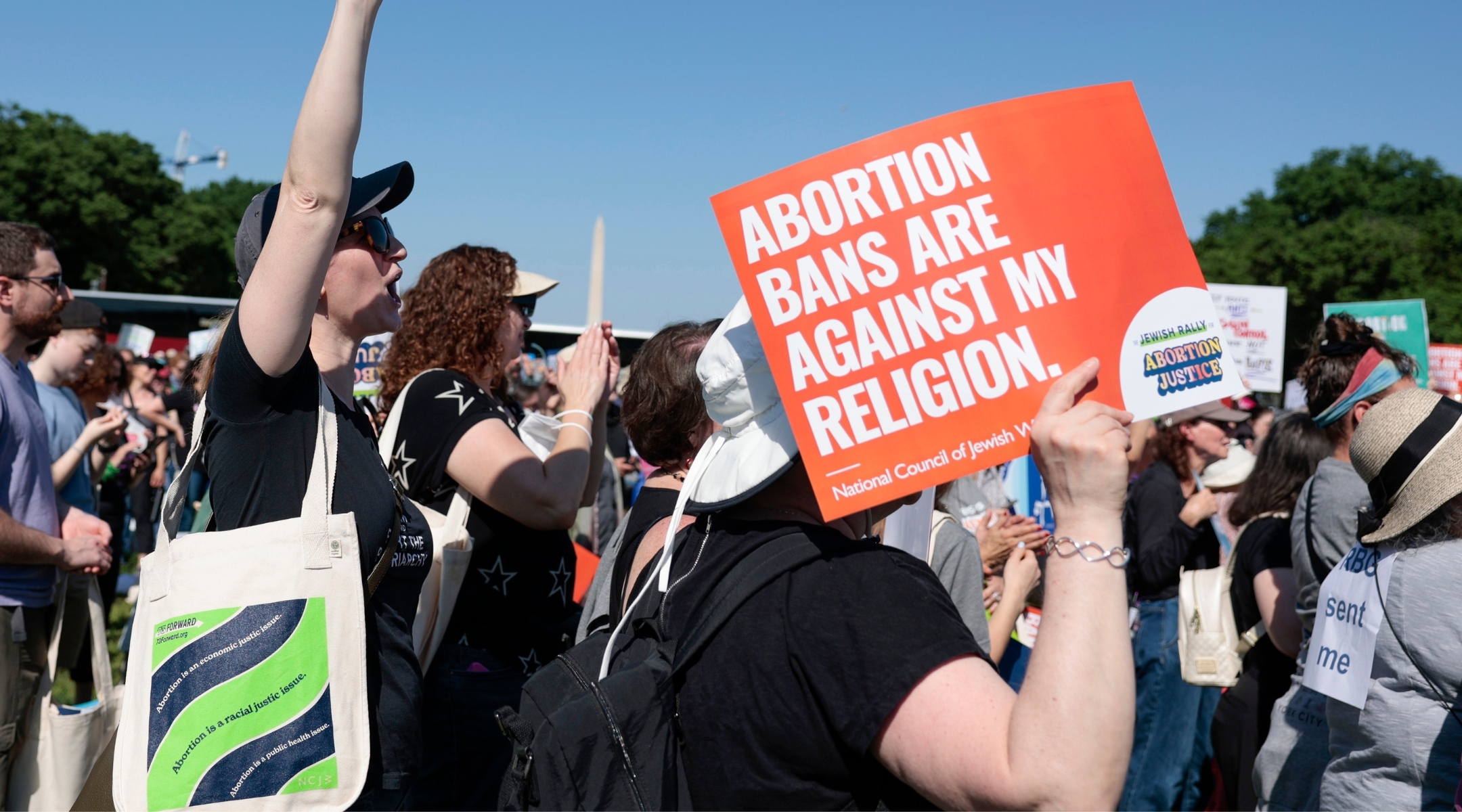

The idea of a Jewish right to abortion being enshrined in U.S. law could, at first, sound strange. But in the wake of Dobbs, as states have adopted new abortion restrictions, Jews and Jewish organizations have filed suit arguing that these restrictions put them in a bind. Jewish laws approach to abortion is generally understood — as much as anything within Jewish law is “generally understood” — to place the well-being of the mother, including physical and emotional well-being, at the center of its analysis. As a result, where an abortion is necessary to protect the well-being of a mother, broadly construed, Jewish law sanctions — and often requires — the termination of the pregnancy. If a mother, motivated by these underlying Jewish values, were to seek an abortion in a state that imposed significant restrictions on such procedures, her religious commitments could run afoul of state law.

Advocacy addressing this tension between Jewish commitments and abortion restrictions is not new. Back in the late ’80s and early ’90s, Agudath Israel of America filed friend-of-the-court briefs encouraging the Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade. But prefiguring much of the contemporary debate, it also argued that those religiously motivated to seek abortions — such as American Jews — ought to have religious liberty protections for such decisions even in the absence of a more general right to abortion. Until recently, though, such arguments received less attention precisely because Roe — and the right to abortion — was the law of the land. Now, in the absence of those protections, Jewish plaintiffs have taken up those arguments and filed suits in a variety of jurisdictions, such as Florida, Kentucky and — most relevant for last week’s developments — Indiana.

The plaintiffs in the Indiana lawsuit, which include both individuals as well as the organization Hoosier Jews for Choice, are not themselves pregnant. But a number of the individual plaintiffs allege that they would like to become pregnant, through assisted reproductive technologies or otherwise. But they fear, given past histories or the realities of using assisted reproductive technologies, that their Jewish commitments may require them to undergo an abortion. And given that Indiana’s restrictions might prohibit such abortions, they have held off becoming pregnant.

An Indiana Court of Appeals found that under such circumstances, the state’s religious liberty protections are likely to require providing women in such circumstances with a religious exemption from the state’s abortion restriction. The logic of the court’s decision is pretty straightforward.

Indiana, like over half of the states, has broad religious liberty protections captured in the state’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act, or RFRA. RFRA, as an initial matter, prohibits the state from substantially burdening religion. Applying this rule, the Indiana court found that the state’s abortion restriction, by prohibiting abortions motivated by Jewish law —and thereby discouraging the plaintiffs from becoming pregnant — imposed a prohibited burden on the religious exercise of the plaintiffs.

The state, however, argued that this burden on religion was justified. Indeed, RFRA allows the state to justify imposing a burden if doing so is the only way to achieve some sort of essential government objective (or, in legal terms, if the burden is narrowly tailored to achieve a “compelling government interest”). To make this argument, the state contended that protecting fetal life is a vital government objective, vital enough to overcome the religious liberty rights of the plaintiff.

But the court ultimately rejected this argument. Indiana’s abortion restriction, it turns out, has lots of other exceptions. For example, it has exceptions — like many other abortions restrictions across the country — for rape, incest, in vitro fertilization and even a narrow exception to protect the physical health of the mother. Where a state grants all these exceptions that weaken the objective of a law — in this case promoting fetal life — then it cannot turn around and claim that its interest is so important that it can’t grant exceptions for religion. After all, how important can the government’s interest be if it already provided all these other exceptions?

So where does this leave us? The decision will presumably be appealed to the Indiana Supreme Court. And it is no doubt possible, either for procedural reasons or otherwise, that the Indiana Supreme Court will reverse the decision. But for now, the fact remains that the first state appellate court to analyze the issue interpreted state religious liberty law to protect the right of Jewish plaintiffs to religiously motivated abortions.

The decision may well have broad impact. Because these cases focus on state law — as opposed to federal law — they won’t be heard by the United States Supreme Court. That means litigation over a Jewish right to abortion will be fought in state courts around the country. Other state courts are likely to take notice of this judicial foray into the issue, especially given that over half the states around the country have identical or nearly identical religious liberty laws.

With an easy-to-follow blueprint now available, last week’s decision may signal that a Jewish right to abortion is no longer merely a theoretical argument. It may, in a world without Roe, be the way of the future.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.