This article is also available as a weekly newsletter, “Life Stories,” where we remember those who made an outsize impact in the Jewish world — or just left their community a better or more interesting place. Subscribe here to get “Life Stories” in your inbox every Tuesday.

Amnon Weinstein, 84, the craftsman behind “Violins of Hope”

In the 1980s, an Auschwitz survivor brought his damaged violin to the Tel Aviv workshop of Israeli luthier Amnon Weinstein. That encounter planted the seed for Violins of Hope, Weinstein’s effort to restore violins owned by Jews before and during the Holocaust and hear them played in defiant concerts the world over.

Weinstein and his son Avshalom eventually collected more than 60 instruments, and the project became the subject of a best-selling book by James A. Grymes and an acclaimed PBS documentary.

“All [the] instruments have a common denominator: they are symbols of hope and a way to say: remember me, remember us,” according to the Violins of Hope website. “Life is good, celebrate it for those who perished, for those who survived. For all people.”

Weinstein was supremely confident and supremely dedicated to his craft. In an interview in 1988 with The Nation, a short-lived Israeli English-language newspaper, he likened himself to master violin makes like Stradivarius and Guadagnini. He recalled his training in Cremona, the Italian town that has for centuries produced luthiers. “And I repay the tradition with my heart,” he said.

A label on one of his half-finished violins bore his name, Amnon Weinstein, in Latin letters and the date in Hebrew. “Maybe centuries from now it will elicit the same gasp as a Stradivarius. Then again, maybe not.”

He had massive affection for his musician clients, if he thought they were a little dim. It drove him mad when violinists and violists would tell him that perhaps the varnish was off. “I made a viola once and everyone at the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra played it,” he said. “They came back and said the sound wasn’t right, maybe it was the varnish — as if they knew anything.” On one occasion, Shlomo Mintz, a virtuoso of the violin and the viola, borrowed the viola others had criticized. “That night he plays beautifully. The next day, they’re all in here, saying, ‘You’ve done something to it, Amnon, it’s changed.’ I did nothing to it.”

He refused to sell the pleaders the viola and kept it in reserve in this apartment for when Mintz was in town.

Weinstein died on March 4 in Tel Aviv. He was 84.

Miranda Frum, 32, a defiant model and writer

Miranda Frum’s work appeared in The Tower, Maclean’s, the Huffington Post and the National Post. (Legacy.com)

In 2018, after returning from a four-year stay in Israel, the writer, model and media strategist Miranda Frum was diagnosed with a large brain tumor. After recovering from surgery in Los Angeles and later, during the COVID-19 pandemic, at her parents’ home in Ontario, she moved to Brooklyn. On Feb. 16, she died in her apartment, her immune system depleted by her many treatments. She was 32.

Frum grew up in Washington, D.C., and later attended the University of Toronto. She travelled to Israel in 2013 on a youth program and stayed, working as a fashion model and contributing to a number of publications, including The Daily Beast and The Tower. “Tel Aviv is an island of lost boys and girls — all of us from near and far who have been drawn to the scene searching for stability, searching for a place to call home,” she wrote in 2014.

Her father, Atlantic magazine staff writer David Frum, remembers her in an essay in the current issue:

Miranda was fiercely independent and stoic, often too independent and stoic for her own good. She had braved dangers all her life. In Israel, she smiled her way through photo sessions as Hamas rockets flew overhead. In France, when anti-Semitic thugs tried to intimidate her and some Israeli friends on the Paris subway, Miranda defiantly spoke Hebrew extra loudly. She urged self-doubting friends, “You need to say ‘f–k you’ to more people more often.” Always ready to listen to the troubles of others, she adamantly refused to discuss her own.

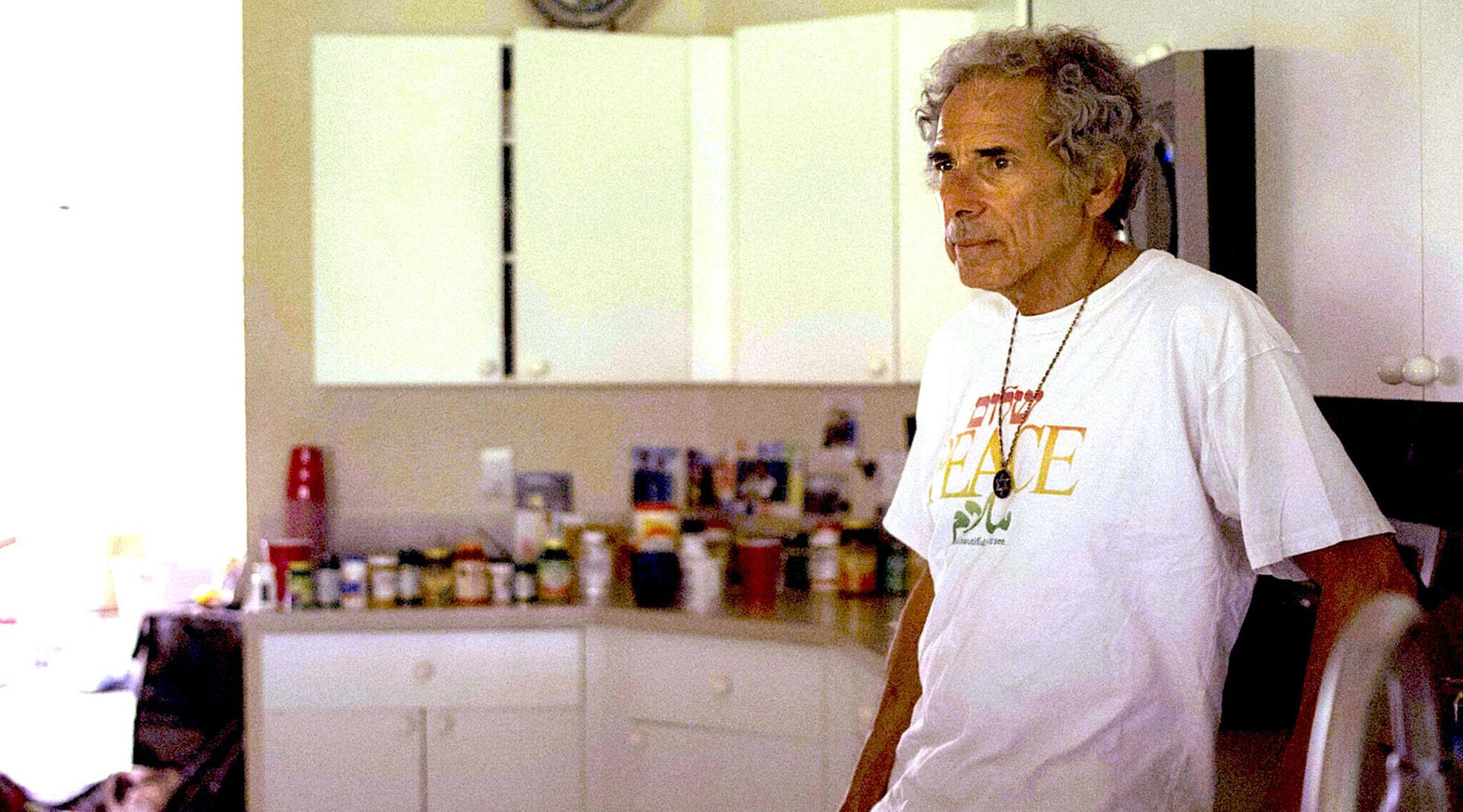

Rabbi Barry Silver, 67, activist and purveyor of “Cosmic Judaism”

Rabbi Barry Silver, who led a lawsuit against Florida’s anti-abortion law in the wake of the Dobbs decision, is shown here in the documentary “Under G-d.” (Courtesy of “Under G-d”)

Barry Silver, a Florida rabbi, lawyer and activist who rarely flinched from a fight on an array of causes, died March 24. He was 67 and had been diagnosed with colon cancer 15 years ago.

The founder and rabbi of the post-denominational Congregation L’Dor Va-Dor in Boynton Beach, Silver filed a lawsuit in 2022 challenging new state abortion limits on religious liberty grounds. He fought successfully to block a developer from building a major project that threatened farmland and wetlands, and led an effort to oppose book bans in Palm Beach County schools.

“He went to bat for the underdog all the time,” the congregation coordinator, Sharon Leibovitz, told the Sun-Sentinel.

Silver served one term in the Florida House of Representatives, and died one day after copies of his new book, “Cosmic Judaism: Uniting Judaism and Science to Enlighten the World,” arrived at his home.

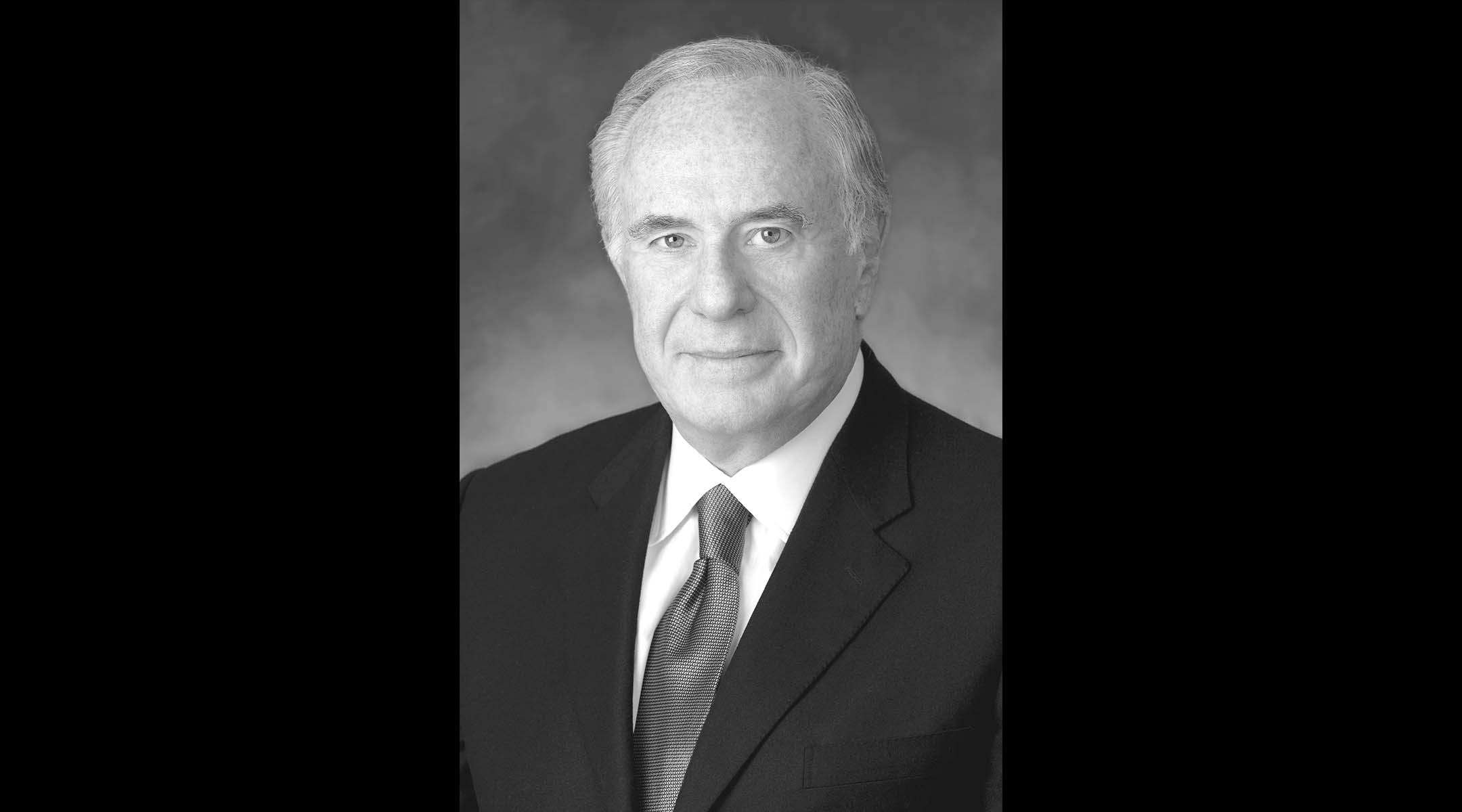

Harvey Schulweis, 83, philanthropist who honored Righteous Gentiles

Harvey Schulweis was the longtime chairman of The Jewish Foundation for the Righteous. (Courtesy JFR)

In 1992, investor Harvey Schulweis, at the behest of his cousin Harold Schulweis, the well-known California rabbi, became chairman of The Jewish Foundation for the Righteous. Over the next 31 years, JFR raised and distributed more than $45 million in financial assistance to aged and needy gentiles who rescued and assisted Jews during the Holocaust.

A managing director of Niantic Partners LLC, a real estate investment company in New York City, Schulweis was also active at UJA-Federation of New York, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the 14th Street Y, and other Jewish communal organizations. He died March 18 at age 83.

“His efforts assured that Righteous Gentiles are able to live out their remaining years with dignity,” JFR Executive Vice President Stanlee Stahl said in a statement, “and that their legacies live on through the educators who teach about their heroism.”

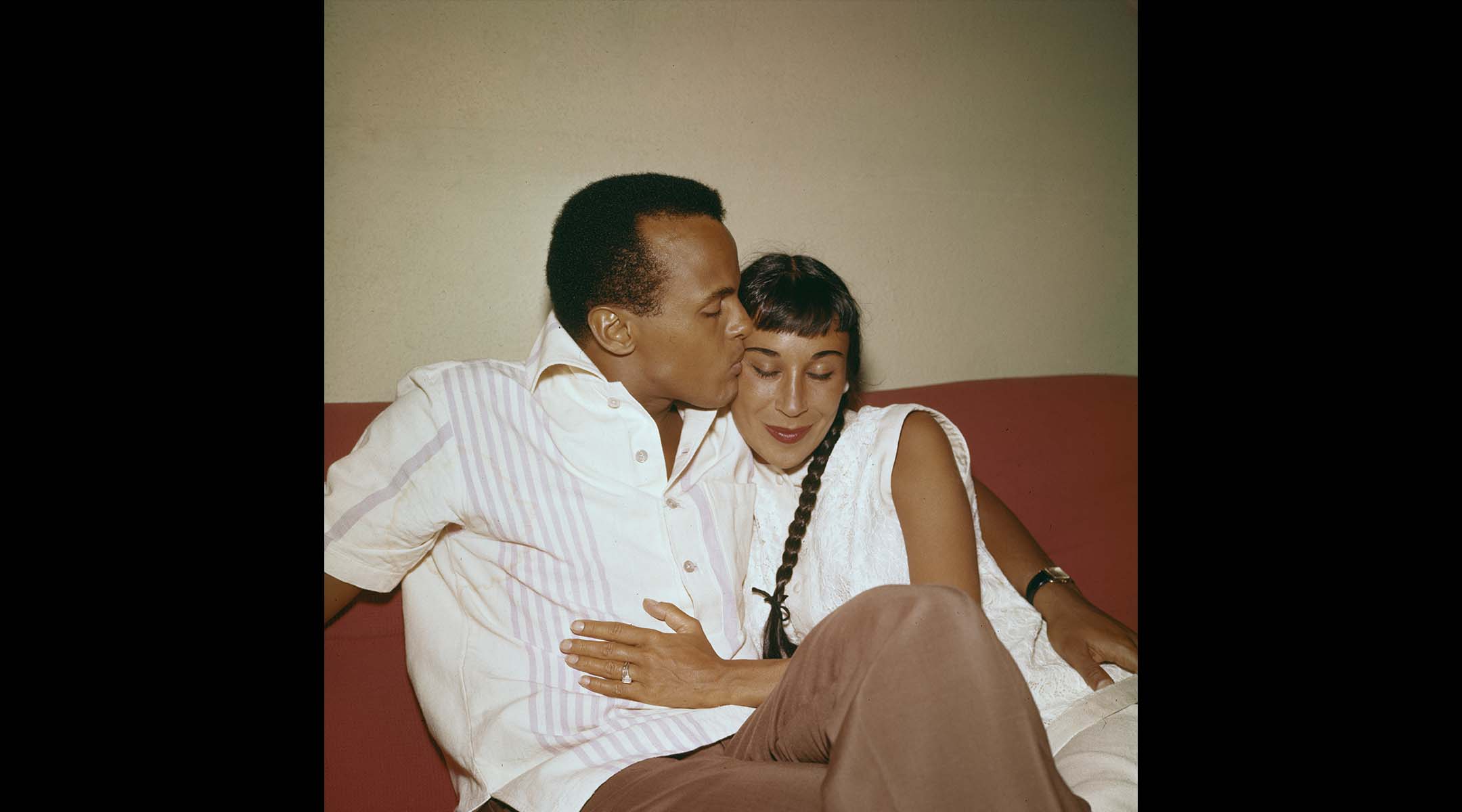

Julie Robinson Belafonte, Harry Belafonte’s wife and fellow activist

Harry Belafonte and his wife, dancer Julie Robinson, at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles, California, Aug. 2, 1957. (Graphic House/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Julie Robinson Belafonte, the Jewish-born second wife of the late singer Harry Belafonte and his partner in civil rights activism, died March 9 in Los Angeles. She was 95.

She was born in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan to liberal parents with Russian Jewish roots. A dancer and an actress, she was the first white member of choreographer Katherine Dunham’s all-Black dance company and appeared in small parts in various movies.

Between meeting Belafonte in 1954 and their divorce in 2007, she joined him in raising funds for the civil rights movement, strategizing with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and holding back channel communications with the Cuban government. She also co-founded the “women’s division” of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and helped to organize, with Coretta Scott King, King’s wife, a women’s march against the Vietnam War.

In an essay for Ebony magazine, Harry Belafonte answered critics who objected to him marrying a white woman and divorcing his first, African-American wife. “I did not marry Julie to further the cause of integration,” he wrote. “I married her because I was in love with her and she married me because she was in love with me.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.