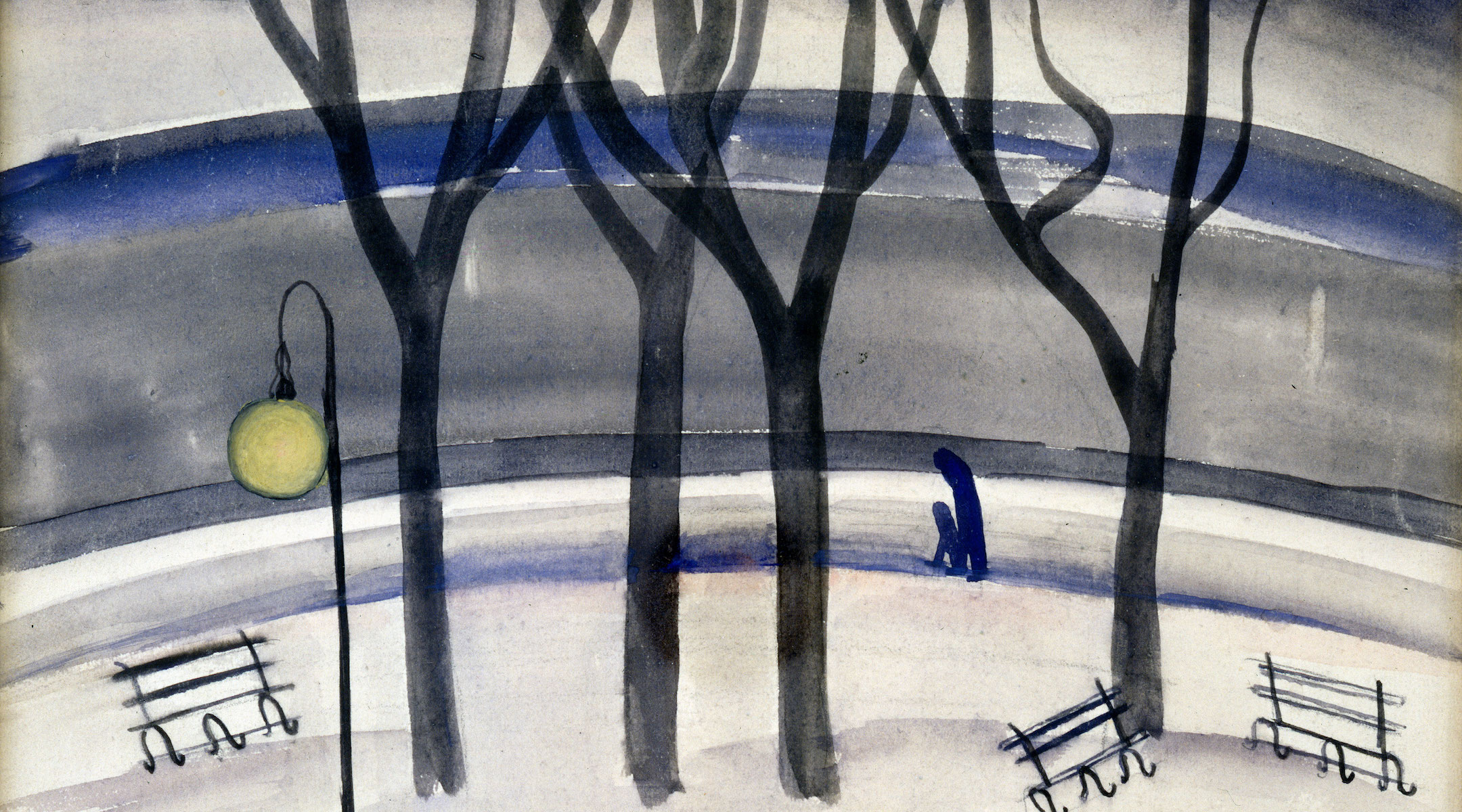

(JTA) — I’m jogging in New York City’s Riverside Park, as I do a few times a week. The air is fresh and my body is happy to be moving. Like many immigrants, I still listen to Israeli radio and read the Hebrew edition of Haaretz every morning. A light-hearted afternoon talk show is playing in my earbuds when the broadcast is interrupted for breaking news. The death of the Israeli-American soldier, Itay Chen, who was considered a hostage, was just confirmed.

The news feels like a punch in the stomach. I met Itay’s father, Ruby, shortly after the Oct. 7 attack. I volunteer with Hostages Families Forum, a tight-knit group that has been organizing rallies, vigils and weekly runs in Central Park. We also coordinate the family delegation meetings with synagogues, local politicians, community leaders, the United Nations secretary general, the Red Cross and others. I remember Ruby Chen handing me the dog tag I wear every day, which says, “Our Heart is Held Hostage in Gaza. Bring Them Home Now!”

The news from miles away punctured my routine, disrupting my equilibrium. Most days, my body can forget the terror of Oct. 7, the worries for the 134 hostages, and the horrific devastation and hunger raging in Gaza. Physically, I am fine, but on Oct. 7, my vision of a just and peaceful future was shaken and assumptions about humanity were shattered.

When I am confused about the world I turn to books. I have always loved studying Jewish texts and I have a deep appreciation for the writings of Sigmund Freud.

In his essay, “Thoughts for the Times on War and Death” (1915), Freud grapples with his disbelief at the carnage of World War I. The war disrupted life as it was known. It brought food shortages, inflation and diseases. Freud’s beloved daughter Sophie died of the Spanish flu in 1920.

Even as modern weapons increased the mortality rate, Freud found human cruelty to be the most unfathomable aspect of the war. “It would seem as though no event had ever destroyed so much of the precious heritage of mankind, confused so many of the clearest intellects or so thoroughly debased what is highest,” he wrote. He adds that the effect of the war, which made friends into enemies, “threatens to leave a bitterness which will make impossible any reestablishment of these ties for a long time to come.”

Like Freud, more than a century ago, I worry about the viability of a peaceful “day after” this devastating war.

I realize the current conflict in Israel and Gaza, even with its extremely high number of civilian deaths and gravely wounded, is dwarfed in comparison to World War I, which claimed over 40 million military and civilian lives, but nevertheless in Freud’s words I see a reflection of our harsh reality.

How can I respond to this awful devastation and to the lack of vision for a peaceful future?

The Jewish calendar offers one answer. Thursday is Ta’anit Esther, a sunrise-to-sunset fast day that takes place every year before the Purim holiday.

The fast commemorates Queen Esther’s fast in the Megillah. Ahashverosh, king of Persia, has approved the evil vizier Haman’s request to kill all the kingdom’s Jews. Esther, a Jewish queen in the king’s harem, agrees to take the risk of approaching the king and averting the decree — if the people fast with her. “Go, assemble all the Jews who live in Shushan, and fast on my behalf,” Esther says to her uncle Mordechai.

I never liked the holiday of Purim. It celebrates a violent deliverance from an utterly senseless decree by an alcohol-addicted king and his vindictive adviser. Queen Esther succeeds in saving her people. But because the king will not reverse his decree, the salvation is through violence and bloodshed.

Like the people in Megillah, we are living at a time when violence seems to be the solution to threats. Why is this happening? Perhaps, like in the Purim story, violence is caused by incompetent leaders. Or maybe as Freud suggests elsewhere, violence is caused by inhibition and repression which then explode in fury. I have been studying the Zohar, the 13th century mystical Jewish text, with a wonderful group for almost a decade. Sometimes, the Zoharic mythical images of a cosmic struggle between divine and evil forces feel more true than modern academic explanations.

In this darkness I find a new meaning in the ritual of Ta’anit Esther.

Fasting is a primal act; it does not require words or explanations. It is felt in the gut, and confronts us with discomfort. By not eating or drinking we enact the most basic physical stress of hunger and thirst.

Because fasting is not a verbal statement, it does not need to articulate a clear demand, it does not need to have a direct recipient. It enacts he pain and despair that so many people are feeling. It is a human physical action radiating a cry for heaven’s and earth’s attention.

Fasting has different meanings in the Jewish tradition. On Yom Kippur, the self-inflicted deprivation is a way to repent from our wrongdoings and ask God for forgiveness. Tisha B’Av is a fast of mourning, commemorating the destruction of the ancient Temple 2,000 years ago and the hardship of life without sovereignty that followed. Ad hoc communal fasts can also be announced to pray for rain at a time of drought.

On March 21, I want to fast like we do on Yom Kippur, to repent for our mistakes and to pray for forgiveness.

On March 21 I want to fast like we do on Tisha B’Av, to mourn the people, the homes, the communities and the institutions that have been destroyed since Oct. 7.

On March 21 I want to fast like we do at a time of drought and the threat of famine, to pray for our basic physical needs.

On March 21 I want to fast like Esther did, to cry in prayer to end the violence and for the safe return of the hostages.

I call on all of you, those who fast every year and those who may be hearing about Ta’anit Esther for the first time, to join me in fasting and praying for peace and safety for all humankind.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.