(JTA) – When a Missouri school district recently received notice that it was the subject of a federal investigation related to antisemitism, its superintendent was as shocked as anyone.

“Honestly, it was a surprise to me when I saw that,” Brandon Eggleston said of the moment on Jan. 2 when the U.S. Department of Education informed Seneca School District that it was opening a Title VI civil rights case into its treatment of Jewish students.

Seneca is a rural district located just south of Joplin, on the border with Oklahoma. There are no synagogues and few Jewish students within district limits. That in itself made the case strange, but the actual incident, as described in the department’s letter, was even more befuddling: An outgoing senior had reportedly delivered a Nazi salute at some point during their school’s graduation ceremony — an incident that no district staff had actually seen, that involved someone who was no longer a student, and that, Eggleston claimed, nobody had reported to the district afterwards.

Now, federal officials were going to descend on the district, and administrators would have to spend resources providing documentation and interviews. Failure to cooperate with this process could cause Seneca to lose federal funds.

“It alleges we weren’t addressing the issue,” Eggleston said of the complaint. “But we didn’t know there was an issue.”

READ MORE: Explore our comprehensive database of Title VI investigations opened since Oct. 7.

The precipitating incident of the Seneca investigation predates the recent outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war and the campus conflicts it has induced. But the confusion in Seneca is increasingly familiar, as a once little-used provision under the federal Civil Rights Act has turned into a new frontier for activists trying to battle antisemitism in schools and universities across the United States.

Originally passed in 1964 as part of the effort to desegregate schools, Title VI protects students from all kinds of discrimination, including based on their “shared ancestry” or “national origin.” Departmental guidelines in recent years have determined those categories include alleged antisemitism on campuses because Judaism is widely understood to be an ethnicity as well as a religion.

But while the provision is designed as a last resort for times when administrators fail to address patterns of behavior, it’s increasingly being used as a first line of defense. Sometimes, it’s being employed in cases where just a single allegedly antisemitic incident has occurred.

A wave of new antisemitism complaints filed since Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel include a growing number filed by entities that lack any connection to the schools they’re targeting; that don’t seek the consent of the students on whose behalf they claim to be acting; and that are open about wanting to undercut higher education in general.

Some of the complaints filed to the education department’s Office of Civil Rights are based on little more than one or two protests or statements that an activist read about in the news or saw on social media.

Want to learn more? Join reporter Andrew Lapin and JTA’s editor in chief, Philissa Cramer, for a live conversation about this story Wednesday, March 6, at 1 p.m. ET. Sign up here.

Taken together, the dynamics raise questions about whether a tool long respected for its power to remedy discrimination could be rendered less potent at a time of particular need for Jewish students.

“If they’re putting their resources into frivolous complaints, if in fact those complaints are frivolous and don’t rise to the level of the standard that OCR has articulated and followed for decades, then that’s a problem,” said Miriam Nunberg, a Jewish former OCR staffer who now consults with families considering filing Title VI complaints. “That’s a big problem.”

Catherine Lhamon, today the U.S. Department of Education’s deputy secretary overseeing the Office of Civil Rights, pictured addressing the National Action Network in Washington, D.C., November 13, 2018, when she was chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

A ‘powerful’ statute with a long history

Columbia Law School professor Olatunde C.A. Johnson has said that Title VI of the federal Civil Rights Act “might just be the most powerful civil rights statute.” In addition to giving the federal government the right to investigate schools when students are allegedly discriminated against, it also empowers the education department to compel schools and districts to take action.

While the department cannot discipline schools merely because an antisemitic incident happens, it can issue penalties when it determines that schools did not meet their obligation to protect students. Last year, the University of Vermont agreed to improve antisemitism training after a Title VI investigation, and last month, a Delaware school district said it would compensate the family of a Jewish student who alleged antisemitic bullying in a Title VI settlement.

In extreme cases, the department can withhold a school’s federal funding as a result of its Title VI findings, though it has not done so in decades.

The Biden administration turned to Title VI in the wake of Oct. 7 as reports of anti-Israel protests, graffiti, death threats and outright violence on campuses piled up. The education department warned schools in a “Dear Colleague” letter to follow Title VI’s regulations around protecting “those who are or are perceived to be Jewish, Israeli, Muslim, Arab or Palestinian,” and Education Secretary Miguel Cardona touted Title VI to JTA as the main antisemitism enforcement mechanism.

Officials have also encouraged Title VI cases. In December, Catherine Lhamon, the department’s assistant secretary overseeing OCR, held a webinar on how to file complaints in conjunction with the Anti-Defamation League, Hillel International, Jewish Federations of North America and the American Jewish Committee. Lhamon emphasized that filing a Title VI complaint is simpler than a lawsuit.

“When you file a complaint, you shouldn’t have to have a lawyer — we wanted to make that really clear,” she said in the webinar. “We want to make sure that every school community knows we are open for business on this topic.”

Earlier this month, the Department of Education told Congress that it has received 183 “shared ancestry” complaints since Oct. 7 (a department spokesperson declined to provide updated numbers to JTA). It has opened 74 investigations based on them to date — triple the number of investigations opened during the entire preceding year, according to its own records.

(The “shared ancestry” complaints represent only a tiny fraction of the Title VI complaints the staff receives in a year, which current and former officials put at between 17,000 and 19,000. The rest of the complaints may focus on disability access, racism, sexual orientation, language barriers or other aspects of identity.)

The investigations take aim at elite Ivy League institutions and rural K-12 public school districts alike; more than half of the post-Oct. 7 crop involve allegations of either antisemitism or anti-Arab sentiment. New investigations are being announced weekly, and JTA has filed Freedom of Information Act requests with the department to obtain more information about what they concern.

Some of the investigations have the potential to directly contradict each other, forcing the department to determine, for example, whether one person’s definition of antisemitism should supersede another’s definition of Islamophobia.

What’s more, a rule on the books paves the way for complaints to be closed without warning: If a civil lawsuit and a Title VI complaint are both filed against an institution due to the same incident, the lawsuit moves forward and the Title VI investigation is closed. That has already happened to at least two investigations opened since Oct. 7, according to department officials.

One of those was at Harvard University, where a pro-Israel student alleged that pro-Palestinian students had assaulted him while he was trying to film a protest; following a lawsuit that also cited the incident, OCR closed its investigation, telling JTA that the relief sought would have been the same.

The other was at the University of Pennsylvania, over the Palestine Writes literary conference in late September. That complaint was filed by the legal activist group Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law, which has filed several Title VI complaints on behalf of pro-Israel students. But it was scuttled when two Jewish Penn students with no connection to the center filed a lawsuit with near-identical allegations of antisemitism.

“It’s one of the unfortunate consequences of a little bit of this Wild West atmosphere that we have right now,” said Alyza Lewin, the Brandeis Center’s president.

Pro-Palestinian protesters on the campus of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, Feb. 20, 2024. (Jeff Kowalsky/AFP via Getty Images)

‘Severe, persistent and pervasive’?

Pro-Israel groups that have long lobbied against antisemitism and anti-Israel activity have employed Title VI in the past and — inspired by success stories like what happened in Vermont — ratcheted up their use of the provision following Oct. 7. The Lawfare Project, for example, has been actively soliciting Title VI clients in WhatsApp groups for Jewish students and on social media.

“We do see now that there is more benefit to aggressively pursuing the rights of Jewish students, because this is something that is now recognized to be a problem,” Gerard Filitti, the group’s senior counsel, told JTA. “More students are coming forward than before, with more of a willingness to put themselves out there and be identified as plaintiffs or complainants.”

The Brandeis Center — whose founder, Kenneth Marcus, oversaw the Title VI process within the education department during the Trump administration — set up a hotline for potential Title VI complainants.

The hotline has received hundreds of calls. “We have never been so inundated with cases,” Marcus recently told NBC News.

Yet despite all these calls, the Brandeis Center has filed relatively few complaints since Oct. 7. Only two complaints the center filed in that period have triggered an investigation (and only one, at Wellesley College, remains active; the other was the Penn complaint). Lewin said it takes time to document “fact patterns,” or evidence of behavior that could establish a hostile learning environment for Jews, that the Brandeis Center can be confident will produce results.

“It is very possible and I assume likely that at least some of them do not have very strong fact patterns,” Lewin said about the many antisemitism complaints filed by novices in the space. “They’re filed by people who are unhappy, who are upset and who feel that they want to do something, and they’re very well intentioned when they file them, but they may very well be filing complaints that might not have a successful resolution.”

Unlike lengthy Title VI complaints filed before Oct. 7, some of the new cases might not relate to any patterns at all. Santa Monica College, for example, says it is being investigated because its student government briefly did not officially recognize a campus pro-Israel group, a decision the college says it rectified the next day. Meanwhile, Tulane University says its investigation relates to a single pro-Palestinian protest that was not held on campus grounds. Lafayette College in Pennsylvania said its investigation was related to a single sign, which the university had swiftly condemned, at an otherwise peaceful pro-Palestinian rally.

“It’s conceivable that a single act could be sufficient to create a hostile environment for a student in school,” Lhamon told JTA. But she added, “It’s more common for a set of factors together to be a constellation that create a hostile environment.”

Unlike with lawsuits, people are not required to demonstrate “standing,” or a personal connection to an incident or school, before filing a Title VI complaint. And investigations are opened without determining whether a case is substantive enough to continue.

Nunberg said that when she worked at the Office of Civil Rights, which she left about a decade ago, the office would open investigations only if it appeared the allegations fit a pattern of a “hostile learning environment” that is “severe, persistent and pervasive” — or if the incident in question was obviously harmful in an “objective” sense.

Now, officials say, the merit of a complaint is not factored in when the department decides which complaints to investigate. Instead, the education department must open an investigation based on any complaint that fits certain criteria: whether it describes an instance of shared-ancestry discrimination; whether some aspect of the alleged incident took place within the past six months (although exceptions are made), and whether the institution at issue receives any federal funding.

Cases can be turned down on technical grounds, but if a complaint meets the basic criteria, Lhamon said recently during the Jewish communal webinar on the department’s approach to antisemitism, “We will open it, period.”

The department believes that investigations can ultimately turn up patterns of wrongdoing that aren’t alleged in the complaints that generate them.

“The investigation requests, when accepted, open up an investigation [that is] very thorough,” Cardona told JTA. “It could even uncover something that wasn’t in the original investigation request.”

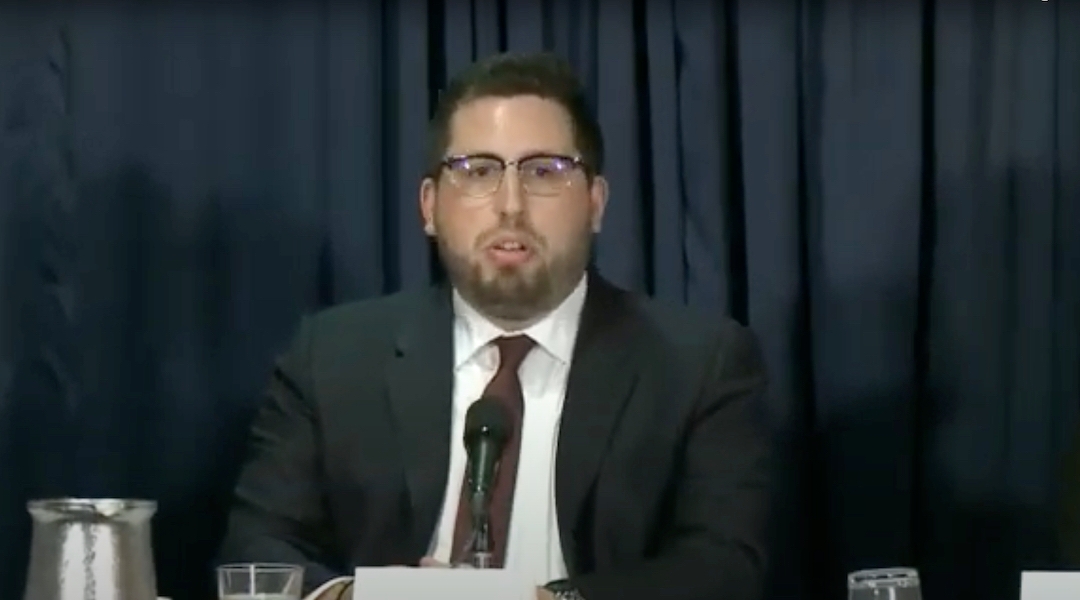

Zachary Marschall, editor-in-chief of the conservative website Campus Reform, has filed 30 Title VI antisemitism challenges with the Department of Education. (Screenshot: GOACTA via YouTube)

The new Title VI warriors

The department’s standards have empowered a crop of emerging activists whose primary approach appears to be responding to what they read in the news. They include individuals with no track record of federal complaints and groups that are part of a broad right-wing effort to purge progressive influence from higher education.

Even before Oct. 7, colleges and universities were under attack from conservatives who castigated the rise of diversity, equity and inclusion programs, known as DEI. Several of them have seen an opportunity in the fight against antisemitism.

A lone conservative named Zachary Marschall has filed more than 30 complaints since Oct. 7, triggering at least nine federal investigations so far. Marschall, the Jewish editor of the right-wing site Campus Reform, is the most prolific filer of post-Oct. 7 complaints to date.

He told the right-wing news outlet Just the News earlier this month that he believed revelations about antisemitism in higher education would bring about “the beginning of the end of DEI.”

To JTA, he said, “If there’s something I can do to help the situation with antisemitism, I’m going to do it.”

Another activist, Justin Samuels, is not Jewish (he claims distant Sephardic ancestry) and has prompted three Title VI antisemitism investigations at universities and K-12 school districts he did not attend. Samuels, who is Black, is a screenwriter who says he talks to conservative legal activists such as Edward Blum. He told JTA he filed his complaints as part of a larger strategy to undo DEI, as well as affirmative action and the Title IX civil rights statute protecting students from sex- and gender-based discrimination. He is also suing Bryn Mawr College, a historic women’s college, for not admitting men.

“The way I think of it, the way to confront discrimination, including antisemitism, is to get rid of that across the board,” Samuels said. “By its nature, DEI violates civil rights laws on multiple accounts, not just on antisemitic or Jewish issues. So I basically say, get rid of DEI.”

Another antisemitism investigation, at Yale University, is based on a complaint filed by the Defense of Freedom Institute, a conservative legal group that seeks to dismantle race- and ethnicity-based policies in higher education.

Donald Daugherty Jr., the group’s senior counsel, said he had a simple answer for why his organization, founded in 2021 by former Trump- and Bush-era education officials, has filed several other Israel-related Title VI complaints since Oct. 7.

“The statute allows third parties like ourselves to get involved,” he said.

‘Boy who cried wolf’?

The Brandeis Center and Lawfare Project have been accused in the past of presenting exaggerated pictures of campus antisemitism, but they say they have always filed complaints on behalf of students with whom they work closely. By contrast, the new crusaders often do not speak with the students on whose behalf they are filing complaints, even as they mention the students by name.

Daugherty said the Defense of Freedom Institute learned about the Yale students named in its complaint from reading news reports.

“I haven’t spoken with them, but I have no sense that they are upset about it,” he said. “In fact, they were asking that Yale do something about this. They themselves are protesting to their school about that. So this is completely consistent with their opinions, at least as expressed in the media.”

One of the two named students declined to comment to JTA about the investigation; a parent of the other did not return requests for comment.

Marschall says his complaints are sometimes informed by his own interviews with Jewish students, but that he also has filed complaints without speaking to anyone on campus. “I haven’t spoken to as many Jewish students as I would like to,” he said, chalking this up to his sense that Jewish students are afraid to discuss their experiences on campus publicly.

At Johns Hopkins University, students say they were surprised when a complaint by Marschall triggered an investigation there this month.

“Initially, we had no idea as to how or why this complaint was filed, especially because it did not come from Hopkins students themselves,” senior Yael Klucznik, a campus pro-Israel activist, told the school newspaper. “Some students are upset because this investigation can sound inflammatory, and as though antisemitism on our campus is thriving. We are worried the investigation can portray Jewish student life as worse than it actually is, and drive away Jewish prospective students.”

For Julia Jassey, a recent University of Chicago graduate and CEO of the advocacy group Jewish on Campus, speaking to Jewish students on the ground is “the most important thing when filing a complaint.”

Jewish on Campus has filed a small number of Title VI complaints in partnership with the Brandeis Center, including the Vermont case that produced tangible results for that university’s Jewish students. “To match good intention with good impact, it’s really important to speak to students and to hear what they need at their specific school,” Jassey said.

When asked about the new Title VI complainants who do not consult with Jewish students, Jassey declined to comment, saying she could only speak for her own group’s policies.

Among the voices concerned about the direction some of these investigations are going is Marcus himself, who worries that antisemitism watchdog groups may be creating “a ‘boy who cried wolf’ problem.”

“We don’t think that it serves any good to file frivolous cases, or cases that are not wanted by Jewish students,” he told JTA. “It doesn’t serve the Jewish community to have shoddy complaints that fall apart upon quick investigation.”

Miguel Cardona, secretary of the U.S. Department of Education, participates in a public event in New York City, April 12, 2023. (Lev Radin/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images)

‘We need more resources’

Whether investigations move quickly remains to be seen. Nunberg said that most cases during her tenure in the Office of Civil Rights were resolved within 180 days, the education department’s stated deadline. But now, the department has open investigations that date back to 2016 — even as fresh investigations appear to be leapfrogging over older ones. Marschall said he has already spent hours sitting down with department attorneys to discuss his complaints, providing them with information they will use to pursue their investigations.

The office is focused on staffing up to wade through the onslaught of complaints and conduct its mounting tally of investigations — but with only half the staff and resources it had in the Obama era, thanks to cuts under the Trump administration that Cardona is lobbying to reverse.

“We have to let our colleagues on the Hill know that we need more resources so that we can get to these cases,” Cardona told reporters during a press briefing on campus antisemitism earlier this month. The department says it hopes to hire another 150 investigators to expedite its cases, on top of the 400 it employs currently.

Marcus rejected the idea that budget cuts during his time leading the OCR were to blame for the caseload and dismissed Lhamon and Cardona’s claims that they need a bigger budget from Congress to adequately handle the new cases.

“There are many factors that impact whether OCR is able to effectively and efficiently address antisemitism cases,” he said. “The budget is a much smaller factor than you might think.”

Marcus added, “What is often needed to move antisemitism cases is a mix of political will, prioritization, and an emphasis on prompt resolution. Those factors are vastly more important than the budget. You could increase the budget of OCR by tenfold and still not get these cases to move.”

Lhamon says she is determined to give each new case the time it deserves.

“These are very serious issues that people are raising,” she told JTA about the people filing complaints. “Anybody who comes to OCR is coming to us with their deepest concerns about students’ experience in schools. They deserve a comprehensive and correct answer.”

Reaching “correct” answers will compel investigators to wade through some of the most complicated issues facing American educational institutions today. And the “Wild West” dynamic appears poised to include potential pistols-at-dawn conflicts between cases.

Marschall’s complaint that prompted an investigation at Arizona State University, for example, rests partly on claims that the school should have disciplined students who chanted the phrase “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” which most Jewish groups say is antisemitic. At the same time, an investigation into a K-12 school district in Minnesota — prompted by a complaint from the local Council on American-Islamic Relations — will determine whether its decision to suspend two students who used the same phrase was Islamophobic.

Cardona insists that the department will be investigating such incidents on a case-by-case basis, rather than making blanket statements about certain phrases or practices.

“It’s hard to broaden and make a statement on the specific cases you’re referring to, nor would I want to comment on open cases,” Cardona said at a recent press briefing, when asked about the contradictory nature of the cases. “What I will tell you is that we need to start with the students feeling safe on campus.”

But without the clarity that could come from more explicit guidance from the department, Title VI runs the risk of “being weaponized” by ideological actors, according to Jonathan Feingold, a professor of higher education law at Boston University who studies equity issues.

“I actually think that the failure to help various constituencies, whether it’s university administrators or students, more carefully tease out those distinctions actually makes it more difficult for universities to ensure that students are able to have a campus free from racial harassment,” Feingold said.

For some schools facing Title VI investigations, the uncertainty is more fundamental. While the department insists that every school is informed as to why it’s being investigated, several schools have told JTA they still have no idea what theirs are about. More than six weeks after an investigation was opened at Whitman College, for example, a spokesperson for the Walla Walla, Washington, private school told JTA they still “do not yet know the specifics of the allegations.”

Back in Seneca, Missouri, the bewildered superintendent is most upset by the investigation’s implication that the school district wouldn’t have known how to address an antisemitic incident if one occurred. His staff, he said, has received training on discrimination, harassment and bullying.

“We’re on the lookout for it,” Eggleston said. “So it’s not something we would take lightly.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.