(JTA) — Rabbi Jules Harlow, a liturgist who edited what became the standard prayer book used in North American Conservative synagogues for a quarter century, died Monday. He was 92.

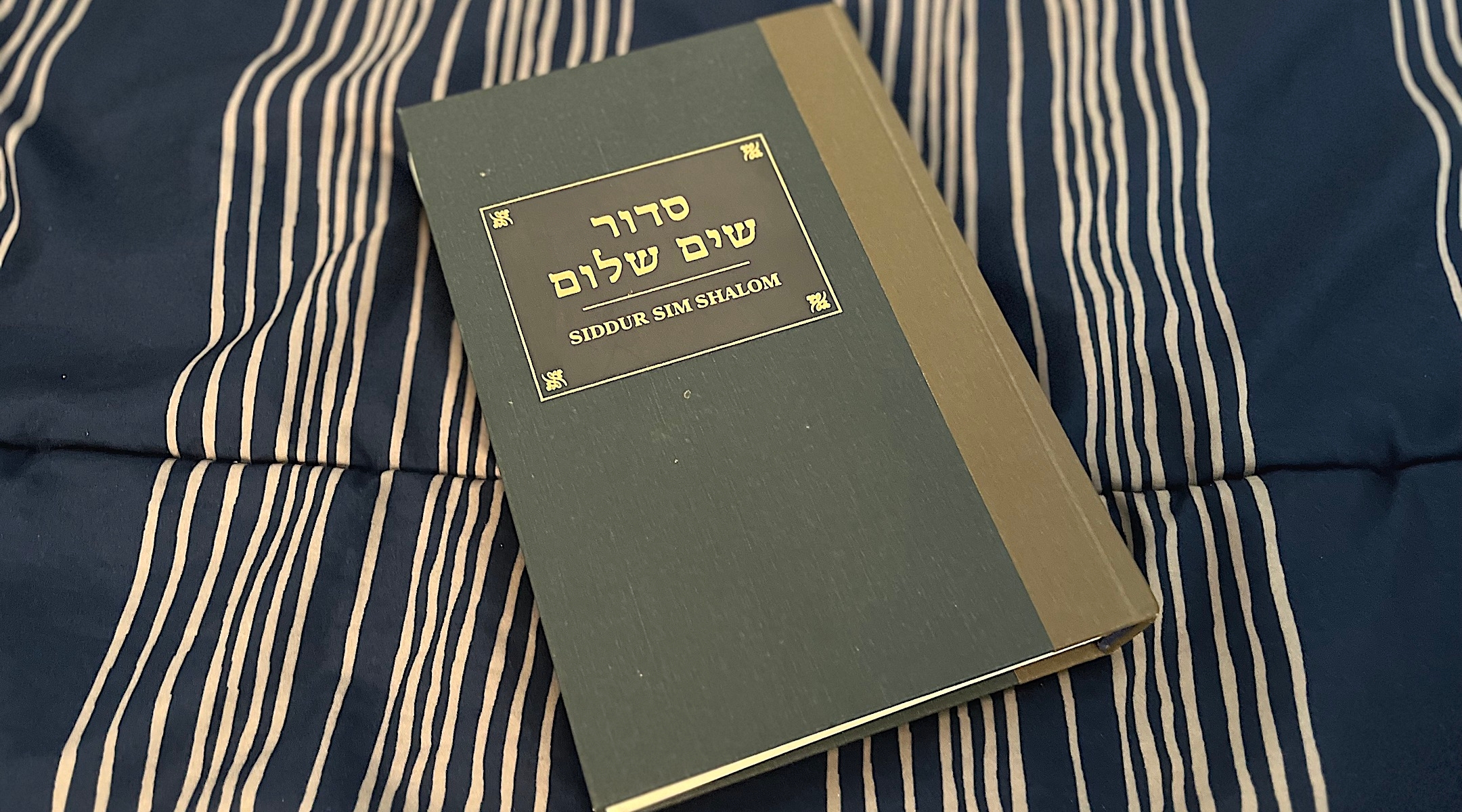

“Siddur Sim Shalom,” published in 1985 by the United Synagogue, the movement’s congregational arm, and its Rabbinical Assembly, replaced the “Weekday Prayer Book,” which was published in 1961. While still traditional in scope, the new prayer book and its High Holiday companion further refined the language and theology of Judaism’s centrist movement, which has long sought a middle ground between the strict traditionalism of Orthodox Judaism and the liberal innovations of the Reform movement.

The innovations of “Sim Shalom” were modest but significant. It offered “alternatives” for those who were uncomfortable with frequent references to animal sacrifices conducted when the ancient Temple in Jerusalem still stood, and provided optional, personal prayers meant to augment the communal, first-person plural voice of traditional prayer.

Reflecting a growing push for gender egalitarianism in Conservative Judaism — which ordained its first female rabbi the year the prayer book came out — “Sim Shalom” also modified early morning prayers. Those blessings, traditionally meant to be recited by a man, thanked God “for not having made me” a woman, a slave or a non-Jew. The new version adopted a positive, egalitarian formulation of the same idea, with blessings that thanked God for having made the worshiper a free person and a Jew.

In an essay accompanying its publication, Harlow assured readers that the changes “affect a very small portion of the recognized Hebrew texts of Jewish prayer. We are linked to Jews of centuries past who have used the same liturgical formulations in addressing our Creator, in confronting challenges of faith and the spirit and in expressing gratitude and praise.”

Rabbi Wolfe Kelman, who at the time of its publication was vice president of the R.A., said “Sim Shalom” was the first prayer book to “incorporate the creation of the State of Israel as a theological reality and the Holocaust as a moral tragedy.”

“What Jules managed to do is not only produce a book with liturgical beauty and a beauty of design and translation, but produce a book which traces the evolution of Conservative Jewish theology,” Kelman told the Long Island Jewish World in 1986.

In 1998, the Rabbinical Assembly released an updated “Sim Shalom” that reflected an even greater shift toward egalitarianism within the movement. The new prayer book, edited by Rabbi Leonard Cahan, included alternatives within the Amidah, the central Jewish prayer, that allowed the prayer leader the option to chant the names of the biblical matriarchs alongside the traditional reference to the patriarchs.

The update also replaced some of the English translations of prayers with “gender-sensitive” language, referring to God as a Sovereign or Guardian instead of a King.

Harlow was wary of some of those innovations. In an essay published in the journal Conservative Judaism, he wrote, “Each of us is entitled to formulate his or her personal prayers. My concern is that changes based upon gender language referring to God disrupt the integrity of the classic texts of Jewish prayer, drive a wedge between the language of the Bible and the language of the prayerbook, and often misrepresent biblical and rabbinic tradition.”

“Siddur Sim Shalom,” edited by Harlow, was published in 1985 by the United Synagogue and the Rabbinical Assembly. (JTA photo)

The Conservative movement has since published two new prayer books — “Siddur Lev Shalem for Shabbat and Festivals,” released in 2016, and “Mahzor Lev Shalem,” a High Holidays prayer book released in 2010.

Born in Sioux City, Iowa, the son of Henry and Lena Lipman Harlow, Harlow studied for the rabbinate at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the Conservative movement’s flagship in New York City. Ordained in 1959, he settled in New York. He joined the staff of the R.A. and served as secretary when it published, under the leadership of Rabbi Gershon Hadas, the “Weekday Prayer Book,” which itself represented what was then considered a contemporary English translation.

As the director of publications for the Rabbinical Assembly, he later oversaw the publication of “Sim Shalom” and its various offshoots, including versions for the High Holidays and weekday services, and “Or Hadash,” a commentary on “Sim Shalom.” He also served as literary editor for “Etz Hayim: A Torah Commentary,” published in 2002, which would become the standard version of the Five Books of Moses found in Conservative pews.

In addition, he served as executive editor of Conservative Judaism, a quarterly published by JTS and the R.A. In 1994, in a bizarre episode reported by the New York Times, a would-be contributor to the journal was so upset that his article had been rejected that he announced plans to meet Harlow and spit in his face.

When the man slipped past security and confronted Harlow at his office, the rabbi gently reminded him that the two had spoken at length about the article and its shortcomings.

“But after two hours you said you did not want to speak to me,” the man said.

“No,” said Harlow, according to the Times. “I said I did not want to speak to you any more.”

Harlow was also a translator of modern Hebrew, including works by the Israeli Nobel laureate S.Y. Agnon.

From 1996 through 1998, Harlow, by then retired from the R.A., served as rabbi of The Great Synagogue in Stockholm, Sweden. In New York, he and his wife Nava (née Shayna Chasman) were members of Ansche Chesed, an egalitarian Conservative synagogue on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

He is survived by his wife, a son, David, a daughter, Ilana, and five grandchildren.

In his introduction to “Sim Shalom,” Harlow noted that the title, found in the daily Amidah, translates as “grant peace.”

“Rabbinic tradition teaches that there is no ‘vessel which contains and maintains a blessing’ for the people Israel so much as peace,” he wrote. “As a community and as individuals, may we ‘seek peace and pursue it.’ May the Master of peace bless us as a community and as individuals with all the dimensions of peace.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.