(JTA) — “One of the first things I learned is that you cannot generalize about the Holocaust experience,” Lawrence Langer told an interviewer for the 2004 documentary, “A Life in Testimony.” “We have to particularize constantly. So that’s what I devoted my life to try to find out: What was it really like?’’

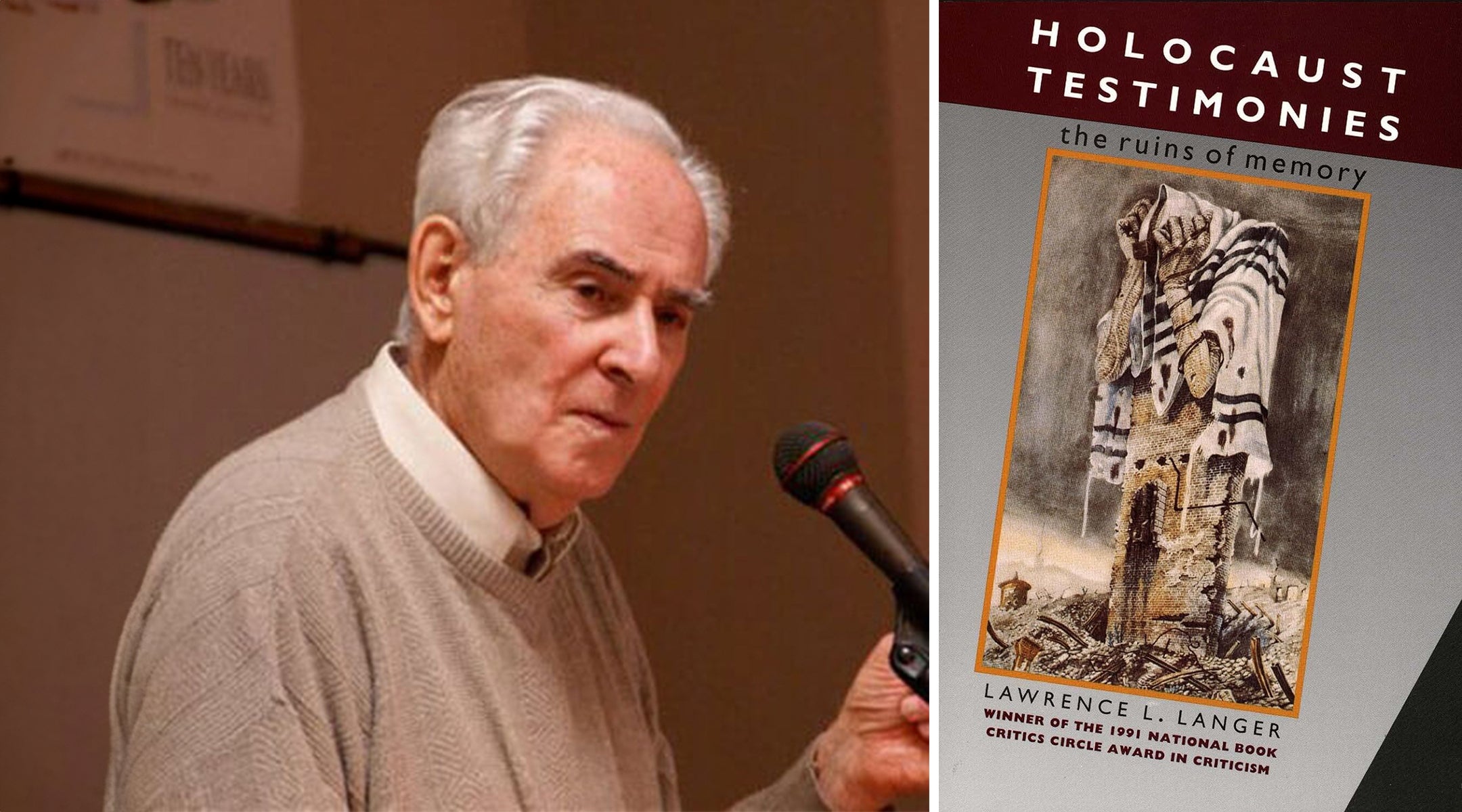

In dozens of books and essays — most famously “Holocaust Testimonies: The Ruins of Memory” — Langer used his skills as a professor of literature to explore what the words of survivors themselves revealed about the genocide and the process of memory. Analyzing hundreds of testimonies gathered by the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University, Langer urged that the memories of eyewitnesses be taken seriously and unsentimentally and not be subjected to a process of mythologizing that plugged survivors into trite categories of “martyrs” or “heroes” who had triumphed over adversity.

A professor emeritus of English at Simmons University in Boston, Langer often argued against the ideas of what he called “trauma theorists,” who sought to find the good or life-affirming in the midst of unspeakable tragedy. “I understand the need to find something good from something that was so bad; I guess it’s a human need, but it distorts the nature of the experience,” he told an interviewer in 2021. “The idea does not emerge from the testimony of Holocaust survivors.

Langer died Jan. 29 at a hospice near his home in Wellesley, Massachusetts. He was 94.

A native New Yorker, Langer found his life’s work in 1964 when he visited the Mauthausen concentration camp and the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp as a Fulbright Professor of American Literature at the University of Graz in Austria. He wrote his first book “The Holocaust and the Literary Imagination” in 1976, following a sabbatical year in Germany. It was one of three finalists for the National Book Award.

“Holocaust Testimonies,” published in 1991, won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism. He was also the editor of “Art from the Ashes: A Holocaust Anthology,” published by Oxford University Press in 1995.

Langer taught American literature at Simmons College from 1958 until his retirement in 1992. At Simmons, he inaugurated in 1965 the first course on Holocaust literature known to be taught at an American college or university.

In 2016, Langer received the Holocaust Educational Foundation’s Distinguished Achievement Award in Holocaust Studies. The City University of New York will award an him an honorary degree posthumously at its commencement ceremony this May.

Langer was born to Irving and Esther (Strauss) Langer in the Bronx in 1929. When discussing his interest in the Holocaust, he would often recall that in the early 1940s, a German Jewish family moved into his family’s apartment building. He did not know consciously that they were refugees, he told another interviewer, but “nonetheless something about the Holocaust was already embedded in me.”

Langer attended City College of New York. Upon graduation in 1951, he and his wife Sandy moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he earned a PhD in American literature at Harvard University.

Following his retirement in 1992, he forged a partnership with his friend Samuel Bak, a painter and Holocaust survivor, writing critical essays for 11 volumes featuring the artist’s work.

Langer published his last two books in 2022: “The Afterdeath of the Holocaust,” featuring essays in which he continued to argue against the tendency to “sentimentalize” the survivors’ experiences, and ”Hierarchy and Mutuality in Paradise Lost, Moby-Dick and The Brothers Karamazov,” his only non-Holocaust related work.

Survivors include his wife, Sandy; a son, Andy Langowitz; a daughter, Ellen Lasri; five grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

In 2020, the Journal of Holocaust Research dedicated an issue in honor of his 90th birthday. “One cannot open a book that deals with any aspect of Holocaust memory, testimony, or literature without encountering not only Langer’s name but also a discussion of his ideas,” the editors wrote in the introduction.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.