(JTA) — Last year, as fighting swirled over the Israeli government’s efforts to reshape the country’s judiciary, Israeli and American critics turned their attention to Arthur Dantchik, a Jewish billionaire who bankrolled a think tank behind the proposed reforms.

After facing protests outside his Philadelphia-area home, Dantchik gave in. He announced that he would stop donating to the Kohelet Policy Forum, saying that Israel had become “dangerously fragmented” and calling for “healing and national unity.”

Months later, Dantchik is quietly sitting on the front row of another fight that many Jews say has deep repercussions for their safety: the battle over antisemitism on social media. Susquehanna International Group, the investment firm founded by Dantchik and another American Jewish billionaire, Jeffrey Yass, controls a 15% stake in ByteDance, owner of the popular video app TikTok. Dantchik also serves as one of five members on ByteDance’s board of directors.

As criticism has mounted over TikTok’s role in amplifying antisemitic and anti-Israel content in the wake of Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, their names have largely stayed out of the public conversation.

The situation is not a perfect parallel to Dantchik’s relationship with Kohelet: Donors have the power to pressure nonprofits by withholding funding, while investors have certain obligations to their companies.

Still, if Dantchik and Yass — who have donated millions to Jewish and Israel-related causes — have pushed for a greater effort to rein in antisemitic content on TikTok, it’s not known. Through a spokesperson, they declined a request for interviews. But it’s clear that they have the potential to force a conversation about Jewish concerns within the Chinese company, as well as incentives not to if increased anti-Israel rhetoric proves good for business.

“Their desire to maximize the value of TikTok may conflict with their desire to promote the interests of the Jewish people and Israel,” said Michael Connor, the executive director of Open MIC, an advocacy organization focused on corporate accountability in the tech industry. “There may be that conflict and they may not want to wade into it. It’s a complicated situation.”

Many social media platforms have faced pressure over content relating to the Israel-Hamas war. But with surveys showing increased criticism of Israel and a rise in pro-Palestinian sentiment among young Americans, many pro-Israel advocates have raised alarm bells over the influence of TikTok in particular.

The company’s top lobbyist in Israel resigned Monday in protest of the company’s alleged anti-Israel bias.

“I resigned from TikTok,” Barak Herscowitz announced in a post on X, formerly Twitter. “We live in a time in which our very existence as Jews and Israelis is under attack and in danger. And in an era of such instability, people’s priorities sharpen.”

He added, “Am Yisrael Chai,” Hebrew for “the nation of Israel lives,” adding in an Israeli flag and flexing muscle emojis.

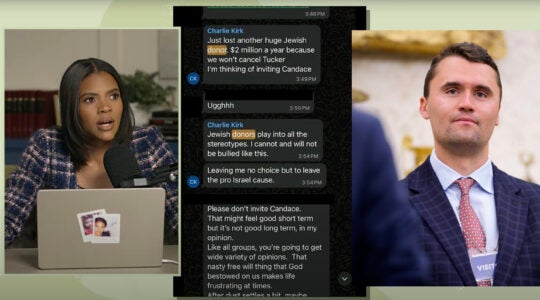

Herscowitz’s public resignation follows repeated instances of Jewish employees at TikTok leaking internal screenshots or speaking anonymously to make allegations of antisemitism within the company.

Criticism of TikTok flared after the results of a survey went viral in November, suggesting that for every 30 minutes that someone watches videos on the platform, they became 17% more antisemitic.

The statistic originates from a graphic shared by tech executive Anthony Goldbloom, based on a survey he commissioned by Generation Lab, a research company specializing in the views of young people.

Presidential candidate Nikki Haley cited the finding during a Republican primary debate. Tesla CEO Elon Musk and Texas Sen. Ted Cruz have also referred to it.

Goldbloom’s claims spread rapidly and have continued even after the company that ran the survey said his conclusions aren’t fully supported by the data. (He did not respond to requests for comment.)

Among the experts who sprung into action to assess TikTok amid the criticism is Yaël Eisenstat, who looked into the social network last year while working as head of the Anti-Defamation League’s Center for Technology and Society. She left the role in January for a job focused on safeguarding the integrity of the upcoming elections.

“Here’s the challenge: As long as TikTok makes it excessively difficult to study their platform, I don’t hold it against people who try to figure out how to do so with the tools available to them,” Eisenstat said in an interview with the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Eisenstat said she has not seen conclusive evidence showing that the company is manipulating its algorithm to promote antisemitism.

“I am not convinced TikTok intentionally has its thumbs on the scale in any direction. Am I convinced that there’s an antisemitism problem on TikTok? Probably. But that is different from implying that they are intentionally skewing information in a certain direction.”

TikTok has rejected accusations that it is a purveyor of antisemitism, saying the company has made special efforts to fight the spread of hate speech and misinformation resulting from the Israel-Hamas war.

From left to right, Jason Citron, CEO of Discord, Evan Spiegel, CEO of Snap, Shou Zi Chew, CEO of TikTok, Linda Yaccarino, CEO of X, and Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta are sworn-in as they testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee at the Dirksen Senate Office Building on January 31, 2024 in Washington, DC. The committee heard testimony from the heads of the largest tech firms on the dangers of child sexual exploitation on social media. (Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

In the absence of transparency about the algorithms behind social media platforms, many critics have focused their attention on the platforms’ owners. As Elon Musk transformed Twitter into X, allowing antisemitic and hateful content to spread in the name of free speech, he became a villain for many on the left, but he also seemed to be courting this attention by incessantly posting controversial statements.

Meta’s primary owner, Mark Zuckerberg, has been vilified on both sides of the political spectrum over content moderation decisions on Facebook and Instagram. On Wednesday, in a Senate hearing on online child abuse and social media safety, South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham told major tech CEOs, including TikTok’s, “You have blood on your hands.”

In the case of TikTok, condemnation has tended to center on TikTok’s Chinese ownership, which is perhaps unsurprising given that many American politicians view China as an enemy, combined with the fact that since Oct. 7, antisemitism and anti-Israel sentiment have become rampant on the Chinese internet and in state-run media. TikTok is also a special case in that it is not publicly traded — unlike Meta, YouTube, or Snapchat — meaning there are fewer avenues for shareholder engagement.

Conservative commentator Jonah Goldberg argued in a column that there’s a relationship between the type of content that is popular on TikTok and China’s interests in its power struggle with the United States.

“China’s fomenting hatred of Israel and Jews appears to be a useful distraction from its own sins and a way to pander to, and encourage, global antisemitism and anti-Americanism,” Goldberg wrote.

Lawmakers have echoed the same ideas. Republican Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida wrote in November on X, “TikTok is a tool China uses to spread propaganda to Americans, now it’s being used to downplay Hamas terrorism.” Democratic Rep. Josh Gottheimer last week posted that “China-owned @tiktok_us has been pushing antisemitic, anti-American, & pro-Hamas content.”

(The company has denied that the Chinese government dictates how it may operate.)

In contrast to the preoccupation with China in the discussion of TikTok’s antisemitism problem, no major public figure or campaign has so far publicly named Yass and Dantchik, whose early investment in the app helped propel them onto Forbes’ list of the richest Americans.

After decades of maintaining a low profile as Wall Street traders, Yass and Dantchik have been repeatedly mentioned in the press in recent years — and not only because of articles tying them to the think tank behind Israel’s proposed judicial overhaul. They have also become known as major donors to Republican campaigns, libertarian causes and philanthropy supporting Israel.

Tax records and other disclosures link the pair with millions in donations to an array of Jewish charities including Birthright Israel, American Friends of Hebrew University, and Hadassah Women’s Zionist Organization of America. Either directly or through foundations they run, they have given to a synagogue near their homes in the Philadelphia area, a Jewish federation in Florida, and the Shalom Hartman Institute.

Dantchik also donated to the 2013 Israeli election campaign of Naftali Bennett, then a right-wing politician heading Jewish Home, a religious Zionist party.

Protesters demonstrating against the Kohelet Policy Forum carry placards linking the group to Arthur Dantchik and Jeff Yass of Susquehanna International Group outside the company’s headquarters in suburban Philadelphia, May 19, 2023. (Rotem Elinav)

Many in the Jewish world who were familiar with and even critical of Yass and Dantchik’s philanthropy didn’t respond or declined to comment for this article, saying they weren’t aware of their ties to TikTok. But the ties aren’t exactly a secret, said one leader of a national Jewish organization, who requested anonymity so that they could speak freely.

“Everybody knows that Susquehanna is a problem — everybody knows that they own this big chunk of TikTok,” the leader said. “All these guys are supposedly right-wing, Zionist, pro-Israel, anti-China and they own part of TikTok but nobody, for a reason that I don’t fully understand, is targeting them. Maybe they are doing stuff under the radar, but I don’t see a campaign asking the Susquehanna guys to divest from TikTok, which is pretty surprising.”

Meanwhile, a representative of the Anti-Defamation League, which accuses TikTok of amplifying antisemitism and anti-Zionism, rebuffed inquiries about whether it was aware of Yass and Dantchik’s stake in the company.

“We don’t accept the premise of the question,” Daniel Kelley, director of Strategy and Operations for the ADL’s Center for Technology and Society, said in a written statement.

“ADL raises awareness about antisemitism irrespective of the faith or orientation of the directors on a company’s board, the company’s investors, or any other potential relationships,’ the statement continued. “We have not studied the capital structure of the company nor have any comment on the information as presented. As we do in any situation, we work to reduce instances of antisemitism and hate wherever they might emerge and utilize all avenues to engage the actors such as TikTok on the relevant issues of concern on the platform.”

Connor, the executive director of Open MIC, has not studied TikTok or been involved in campaigns targeting the company but he concluded, based on his experience engaging shareholders of other tech giants including Meta, Alphabet, Amazon, Apple and Microsoft, that Yass and Dantchik are facing a delicate set of circumstances.

Social media platforms can profit from outrage and friction, which have been shown to drive increased user attention. “The business model in many ways benefits from the spread of hate speech and conflict, because people click on it more and they react to it more,” Connor said.

Concerned board members can’t always push for changes because they are legally required to represent the financial interests of investors — they would have to argue that becoming a haven for hate is ultimately bad for business.

But even when a social media company is convinced it has a problem and wants to address it, a solution is often elusive. Identifying and removing content that promotes hate is notoriously difficult.

“The question is: To what degree are they capable of removing content?” Connor said. “That’s an open question and they may not be able to. One of the biggest concerns about social media is that the technology has outpaced our ability to control it in a responsible way.”

Amid all the challenges and unknowns, Connor said one thing is certain about Yass and Dantchik.

“They can make their voice heard at the board of directors,” he said. “They can raise concerns.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.