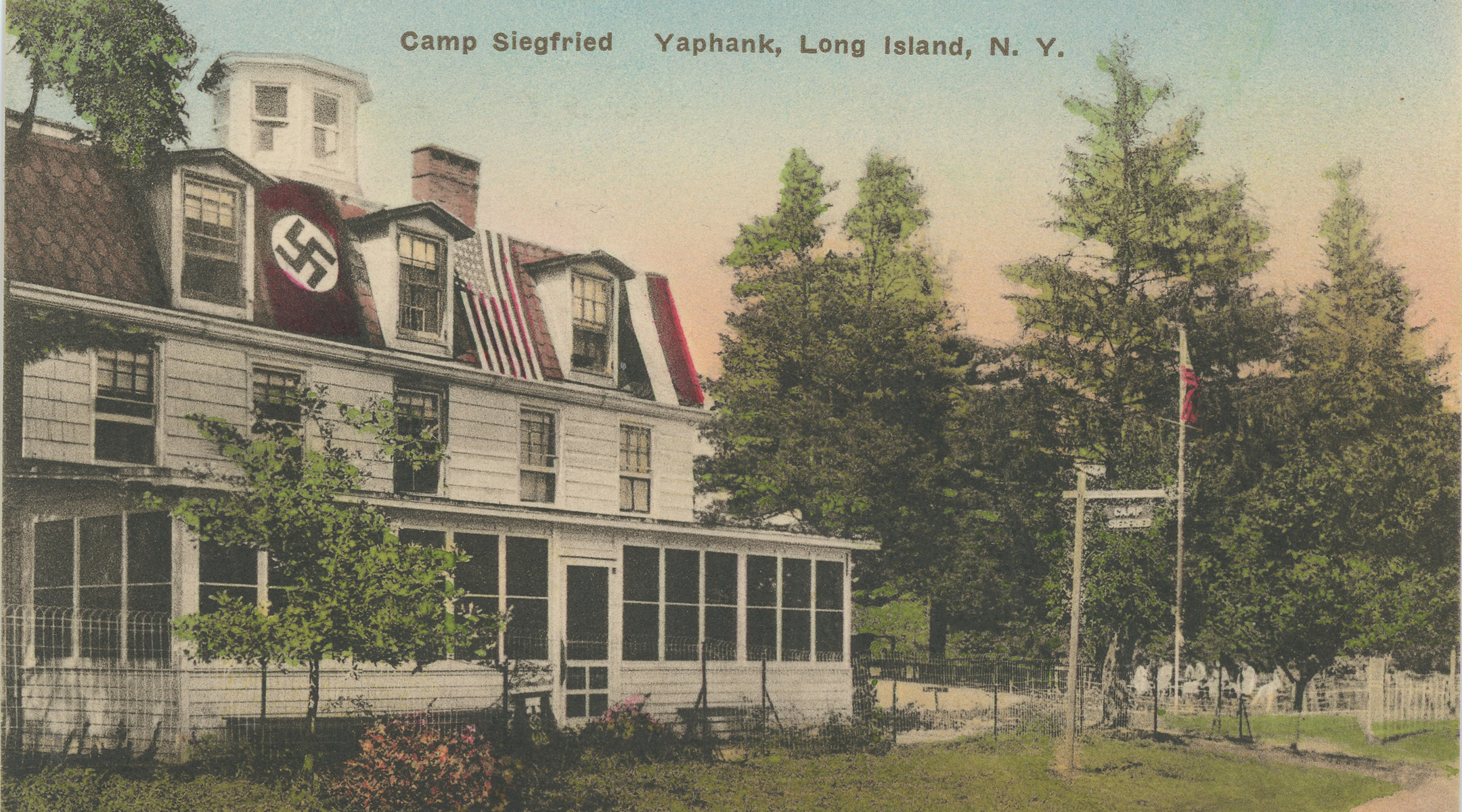

(New York Jewish Week) — Picture a group of children having fun at summer camp, learning archery, swimming and playing tug of war, all while the Nazi flag flies next to the American flag. Or a packed crowd at Manhattan’s Madison Square Garden, where men and women of all ages give the Hitler salute.

These are some of the real-life disturbing images depicted in “Nazi Town, USA,” a new documentary about the German American Bund — a pro-fascist, pro-Nazi organization that, at its peak, had some 100,000 members in the United States — that premieres on “American Experience” on PBS on Tuesday.

The German American Bund (bund is German for “organization”), founded by German immigrant Fritz Kuhn in Buffalo in 1936, was created to promote pro-Nazi ideology within the United States. Kuhn and his cronies relied upon patriotic imagery such as George Washington and the American flag to attract Americans of German descent as members — but as Kuhn himself said, the organization’s goals were to create a “socially just, white gentile-ruled United States” and a “gentile-controlled labor union free from Jewish Moscow-directed domination.”

Filmmaker Peter Yost, who wrote and directed “Nazi Town, USA,” told the New York Jewish Week that he first became interested in the history of Nazi organization while helping his friend Marshall Curry with his Academy Award-nominated short documentary “A Night at the Garden,” which used archival footage, some of which can also be seen in “Nazi Town, USA,” of the 1939 “Pro-American Rally” at Madison Square Garden held by the Bund.

“It’s amazing footage and it’s incredible that there are 20,000 of these Bund members inside Madison Square Garden,” Yost said. “It certainly begs the question, ‘If you can get 20,000 of them in this one spot, what the heck is going on in America at the time more broadly that enables that to happen?’”

That’s the central question Yost explores in “Nazi Town, USA.” Using archival footage and photos of the Bund’s activities — many of which were shot by the Bund itself for promotional purposes — as well as interviews with historians, the film chronicles the rise and fall of the organization from its beginning through its peak and its ultimate collapse in 1941.

The Bund was just one of hundreds of right-wing and fascist-friendly groups in the United States in the 1930s, but by focusing on one group, Yost was able to explore how and why fascism was so appealing to Americans at that time. “Often the best films, in my opinion, are ones that use a narrow story to tell a much bigger story,” he said. “While the Bund matters and is interesting, it really is a means to get at these bigger questions and explore these bigger ideas.”

Headquartered in New York City, the Bund was organized into 50 districts nationwide — indeed, the film’s name “Nazi Town, USA,” is meant to indicate that Nazi ideology, for a time, was widely embraced across the country.

“It resonated here for a reason,” Yost said. “It tapped into a lot of elements in America that were fascist-friendly, like the racist Jim Crow laws or very restrictive and race-based immigration laws. These were things that Hitler and the Nazis admired and even in some cases adopted for their Nuremberg race laws. They saw in many ways America as fertile ground for their ideas.”

A postcard depicting Camp Siegfried, a pro-Nazi summer camp in Yaphank, Long Island, in the 1930s. (Courtesy the Longwood Public Library’s Thomas R. Bayles Local History Room)

According to historian Bradley W. Hart, who appears in the film and is the author of “Hitler’s American Friends: The Third Reich’s Supporters,” certain “dark impulses” in American society come to the surface under the right circumstances — which is exactly what happened in the 1930s.

“This was a period of incredible turmoil in the U.S. You have the Great Depression, you have people who have lost everything,” he told New York Jewish Week. “At this moment, when you have dictators in Europe, people like Hitler and Mussolini, who are preaching hate and preaching that they have a solution to the real pain that people are feeling, it’s inevitable, unfortunately, that some will be attracted to that message.”

Enough people were interested in the Bund to make a business out of summer camps for families and children across the country, the most famous being Camp Siegfried in Yaphank, Long Island — a Suffolk County hamlet that also had a community called German Gardens with streets named after prominent Nazis.

“They had everything you would expect in a summer camp,” Hart said, emphasizing that many of the campers were city kids. “And this was a period when if you lived in the inner city, you didn’t necessarily have a car. You were looking for recreational activities for you and the kids. You were looking to get out of the city when there was no air conditioning.”

Reports from those camps are unsettling today precisely because of how relatable they are, he added.

“The accounts are anodyne-sounding in some ways: It’s a bunch of guys sitting around and drinking beers and the kids are playing and they’re talking politics,” Hart said. “It’s the kind of politics we find deeply appalling today, but the scene itself isn’t that different perhaps than what we might expect to go on in a camp — but then you have this deep ideological current of Nazism running underneath everything.”

At these camps, Nazi flags were flown on flagpoles and swastikas adorned the bungalows’ roofs. What’s more, according to Hart, the Bund didn’t conceal their antisemitism in part because they thought many Americans would agree with them.

“They couch it as anticommunism,” he said. “They’re open about the kind of antisemitism that they think is going to appeal to a broader swath of Americans.”

The strategy worked, for a while: When the FBI investigated the Bund because they were looking into Nazi activities in the United States, director J. Edgar Hoover wasn’t that interested in shutting down the organization because he was so anti-communist.

While it’s easy to draw parallels between the 1930s and today — the rise in antisemitism, the divisive American politics — such comparisons aren’t explicit in the film. But viewers can draw their own conclusions.

“It’s a film about fascism and non-democratic politics. It’s a film about a moment in America where a number of people wondered if the American experiment was failing,” Yost said. “We were looking at a specific moment in time, and exploring why these ideas captured the imaginations of some people at that time, and so it engages a number of big questions that in many cases we’re still asking today.”

The documentary also shows that many Americans were willing to stand up to Nazism and fascism, such as journalist Dorothy Thompson, who warned about Hitler in her articles and who was also at the Madison Square Garden rally, heckling. There was a group of tough Jews known as the Minutemen who would break up meetings of the Friends of New Germany, a precursor organization to the Bund, and the Chicago Daily Times reporters John and James Metcalfe went undercover and infiltrated the Bund so they could report on their plans.

Isadore Greenbaum, a 26-year-old Jewish plumber, risked his life to rush the stage at Madison Square Garden to yank the cables from Kuhn’s microphone. He was immediately beaten by the Bund’s security team, though the NYPD intervened and escorted him out.

“He really tries to strike the first blow against fascism in the United States — this is still years away from the U.S. fighting fascism in a physical way anywhere as a country,” Hart said.

As large as the Madison Square Garden rally was, the fighting there represented a turning point for the German American Bund.

“That’s an incredibly powerful moment … because it reveals what the Bund is,” Hart said. “When that violence erupts on the floor of Madison Square Garden — the most important, I would argue, political and social venue in the country in 1939 — people can’t turn away from that. It becomes clear that the Bund is not just a perhaps eccentric cultural organization that has some views that most people don’t agree with, it truly does have a violent undertone to it.”

The Bund collapsed shortly after the rally, when Kuhn was found guilty of embezzlement and tax evasion. Though its heyday is largely forgotten today, Yost hopes that this documentary will help serve as a reminder and a wakeup call about the precarious nature of democracy.

“It can be disturbing to see how deep the roots are for some of these ideas in America,” he said. “But it can be somewhat comforting to see that America has faced great challenges before, and has raised deep existential questions about our system of government, and has come out the other side.”

“Nazi Town, USA” premieres on “American Experience” on Tuesday at 9 p.m.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.