(JTA) — Hasia Diner, renowned scholar of American Jewish history, celebrates her retirement from New York University on Sunday. For 26 years, Diner served as the Paul and Sylvia Steinberg Professor of American Jewish History and continues to serve as the director of the Goldstein Goren Center for American Jewish History.

It would be impossible to overstate Diner’s impact on the study of American Jewish history. A brilliant and unusually prolific writer, she authored and edited 21 major volumes over the course of her storied career (most distinguished historians author no more than five). Even more unusually, her work has consistently disrupted unexamined assumptions and broken new ground in the field. A social historian of the highest caliber, she examines history from the perspectives of the everyday people who lived it. Taking on topics as disparate as Black-Jewish relations, immigrant foodways, Jewish women’s history and Holocaust memory, her interests have always been as capacious as they are innovative.

She has earned the highest honors in the field, including a Guggenheim Fellowship; the Lee Max Friedman Award for Distinguished Service from the American Jewish Historical Society; the Saul Viener Prize for Outstanding Books in American Jewish History; a James Beard Nomination for food writing; and numerous National Jewish Book Awards.

While Diner herself transitions to retirement, her students continue her legacy by producing groundbreaking work in the field. Here, we’ve collected tributes from seven of her students — themselves noted historians, researchers and educators — describing how Diner’s scholarship and mentorship inspired their own careers.

For scholars of American Jews and the history of migration, for her colleagues, students, and devoted readers, it is high time to take stock of her influence and accomplishments.

A readiness to question received wisdom

Hasia always stresses the importance of evidence. She has an amazing capacity for archival research and an almost uncanny ability to put her finger on the right questions to ask in order to allow her research to yield new answers.

Her scholarship flows from her readiness to question received wisdom and her desire to figure out what actually happened. It may sound self-evident to say that historians rely on historical evidence when they write, but it can be surprisingly easy to get hemmed in by faulty assumptions and limited sources. Hasia teaches her students that a good historian has to be brave in their willingness to challenge the claims of previous scholarship and creative in their ability to consider which perspectives and ideas other scholars may have overlooked.

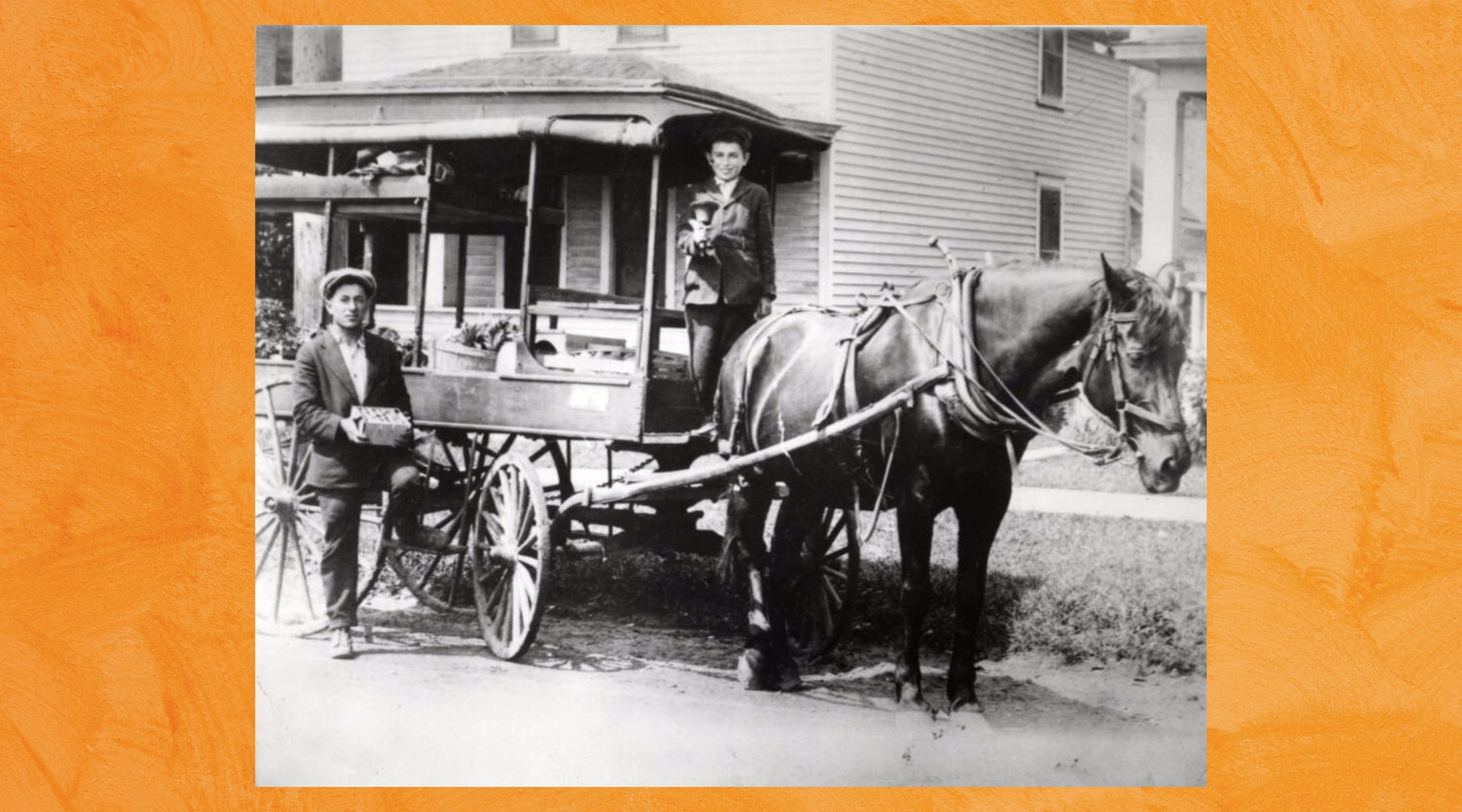

Hasia is a great historian. She is tenacious and courageous in her scholarship. In the introduction to her book “Roads Taken: The Great Jewish Migrations to the New World and the Peddlers Who Forged the Way” (2015), she describes her love of work that allows her “to take something fairly obvious and to invest it with historical meaning.” I think that quote really captures her approach to writing history. Peddling was so ubiquitous that historians almost took it for granted. Hasia asked what we can learn from the lives of “humble” peddlers, then she dove into archives around the world in search of evidence to help her figure that out. Her work breaks new paths. I cannot imagine a better model for how to be a historian.

Jessica Cooperman is Associate Professor of Religion Studies and Director of Jewish Studies at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Her research focuses on 20th century American Jewish History and American Judaism. Her book, “Making Judaism Safe for America: World War I and the Origins of Religious Pluralism,” received an honorable mention for the Saul Viener Prize in American Jewish History. She is currently working on a history of Passover seders in the United States.

Diner’s books, writes one of her students, offer “a history of everyday American Jews,” including “people who were not typically placed at the center of academic histories at the time she began her career.” (Harvard University Press; Yale University Press; NYU Press)

Giving voice to everyday people

When I was a graduate student crafting what would become my dissertation and then book, Hasia was the first senior scholar I spoke to who didn’t seem to think that my interest in the history of Jewish summer camp, with an eye towards the experiences of children and teenagers, was a topic of little significance. At the time, I thought this was because she herself had gone to camp and thus instinctively understood the intense hold it can have on the young. As I got to know her scholarship more, however, I came to understand that her support of my research interests aligned with her own approach. As a social historian, each of Hasia’s books is a history of everyday American Jews. Sure, she has written about Jews in positions of power and leadership, too. And yet the heart of her work focuses on the lives of immigrants, peddlers and women, people who were not typically placed at the center of academic histories at the time she began her career.

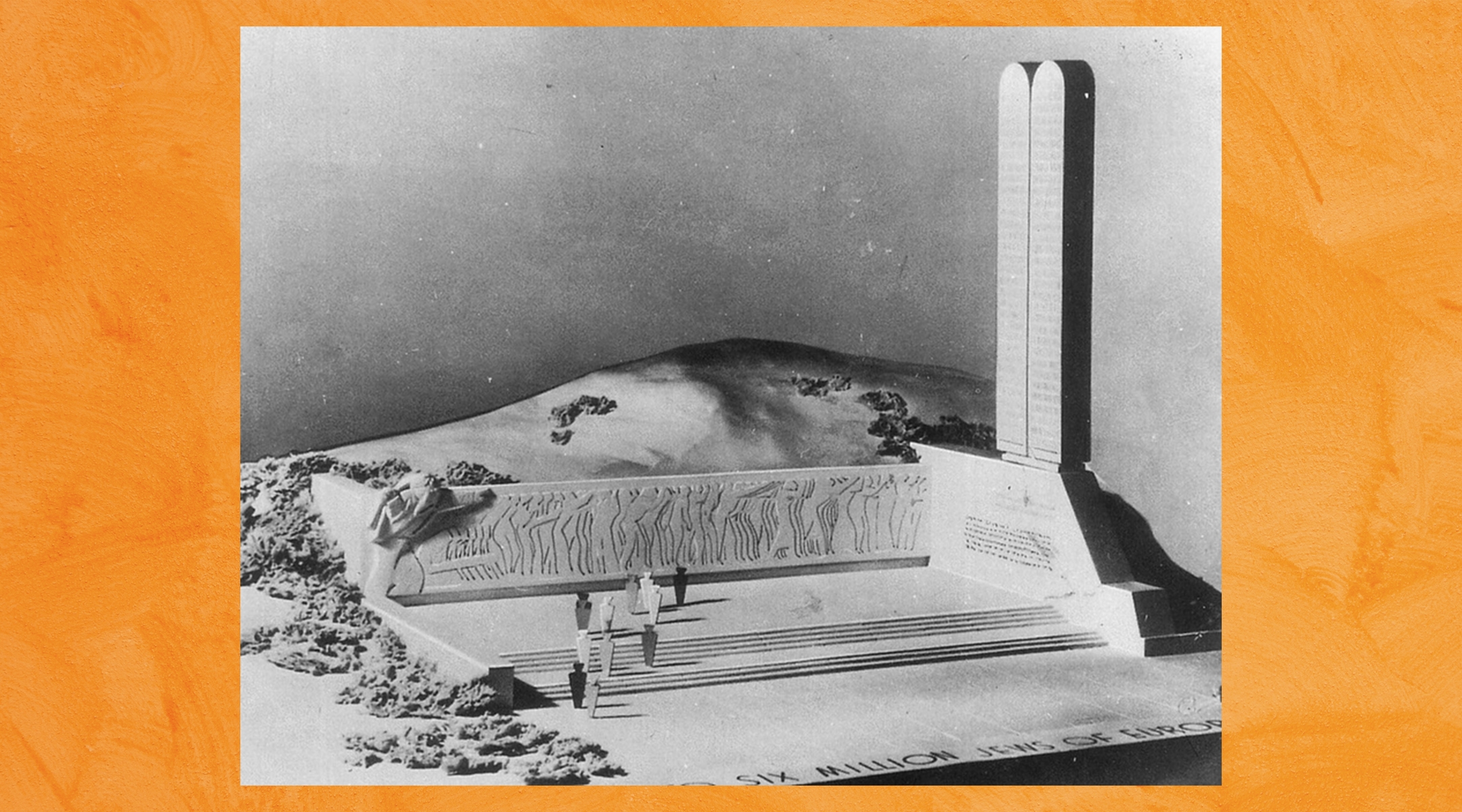

Her focus on everyday people is not an act of altruism or activism. Rather, Hasia believes that using this lens gets to the heart of how history has been experienced and how it has unfolded. Her work has proven this time and time again. Take, for example, her 2009 book “We Remember with Reverence and Love: American Jews and the Myth of Silence after the Holocaust, 1945-1962.” In it, Hasia shows, in painstaking detail, that American Jews talked about the Holocaust in its aftermath — not just a little, but a lot — proving that the prevalent notion that Jews were silent for decades after the Holocaust’s wake was a kind of mythology. Everyday people were, in fact, talking about it; educators taught kids about it; communities created memorials and ceremonies to the Six Million. Paying attention to Jewish communities across the country, and sources others hadn’t considered, enabled her to write this absolutely groundbreaking book, one that altered that particularly pervasive narrative both inside of academia and out.

Luckily, it’s no longer groundbreaking to give voice to everyday people in American Jewish history. Plenty of us — her students and others — are doing exactly that all the time. The fact that it’s now normal, accepted and taken seriously, though, is because of pioneering social historians like Hasia, whose books will undoubtedly stand the test of time.

Sandra Fox is visiting assistant professor of Hebrew Judaic Studies and director of the Archive of the Jewish Left Project at New York University, and founder and executive producer of the Yiddish-language podcast Vaybertaytsh: A Feminist Podcast in Yiddish. She is the author of “The Jews of Summer: Summer Camp and Jewish Culture in Postwar America.”

“Piercing, exciting and vaguely destabilizing”

I had just begun my dissertation research under Hasia Diner’s supervision in 2009 when her book “We Remember with Reverence and Love” dropped. In it, she shattered the widely accepted myth that American Jews were silent about the Holocaust between the end of World War II and sometime in the 1960s.

I had already chosen her to train me with the skills and mentality of a historian, having come to grad school with little background in academic Jewish studies or in history as a discipline. That book helped solidify some other things I had sensed about her while I was her MA student: that her questions were piercing, exciting and vaguely destabilizing, that she pursued their answers meticulously even if they lead to uncomfortable truths. She was also incredibly careful to ensure that her truth claims where unassailable with colossal evidence.

By example, Hasia taught me that one of the core tasks of a historian is to question received wisdom and ask new questions about subjects we already understand. We should, in the phrase of Abraham Joshua Heschel, know what we see (that is, carefully examine claims and evidence) rather than see what we know (that is, confirm our biases by selectively noticing the world).

Her mentorship-by-example certainly gave me some of the courage I needed to write “The Jews’ Indian: Colonialism, Pluralism, and Belonging in America” (2019), a book that situates American Jewish history in the context of European settler colonialism and the genocidal process at the very root of our collective existence in North America. It’s a history that insists that Jews in the U.S. (and Canada, Argentina, Australia and plenty of other migrant destinations in the southern and western hemispheres) need to be thought of as not just immigrants at the center of their own Jewish drama of migration and mobility, but also as actors in the long epic of settler societies built over Indigenous lives.

Like the Jews Prof. Diner studied who advanced early 20th-century African-American interests (“In the Almost Promised Land: American Jews and Blacks, 1915-1935”), I too found liberal and progressive Jews who devoted their lives to advancing Native America and countering the forces of America’s “original sin.” They made significant impacts in public awareness and helped establish some of the techniques of Indigenous resistance and resilience — such as using the courts, legislation and the like to advance interests before the Native American Red Power movement of the 1960s and ’70s.

We historians write books we hope will reach huge readerships. At the same time, many of us have one person we bear in mind as our most important reader. For me, that’s Hasia.

David S. Koffman is the J. Richard Shiff Chair for the Study of Canadian Jewry and an Associate Professor in the Department of History,at York University. He is a cultural and social historian of modern Jewish life, with a specialization in Canadian and U.S. Jewries.

In “We Remember with Reverence and Love,” Hasia Diner challenged the notion that American Jews were largely silent about the Holocaust in its immediate aftermath. Above, Erich Mendelsohn and Ivan Meštrovic’s 1951 design for a Holocaust memorial in Riverside Park, New York, that was never realized. (YIVO Institute for Jewish Research)

Mentoring a new generation of scholars

As a chronicler of the American Jewish experience, Hasia left no communal myth unchallenged. Whether it was Jewish nostalgia for their imagined community on New York City’s Lower East Side, or the complicated motivations behind early 20th-century Jewish advocacy for Black civil rights, or the extent to which American Jews actually remained silent in the years immediately following the Holocaust (they didn’t!), Hasia fearlessly forced her readers, fellow scholars and lay people alike, to contend with communal memories and appreciate the richness that came with unsettling myths of American Jewry’s commonly assumed past.

Hasia saw the power in challenging narratives, but also the beauty in telling more nuanced accounts of Jewish engagement in modern America, all while using only the sparsest of passive voice in her prose. Hasia inspired her students to do the same, uncovering stories embedded, but often rendered invisible, in both Jewish and American popular memory and bringing these stories to light. She continuously professed her belief in her students and their ability to conduct diligent and important research to help shed more light onto the ways in which Jews transformed the American landscape through activism, acculturation and even apathy.

She was the professor who saw value in my researching what others dismissed as the flightiest of subjects: the Jewish sorority system in American universities and their encounters with postwar social movements. After rolling her eyes and exasperatedly offering her signature “huff” of outrage when hearing about the reactions of other historians to the topic, Hasia declared that any group boasting thousands of members surely had an important story to tell and a question to be answered through archival research and dedicated study. When a fellow graduate student and I approached Hasia identifying a gap in books on American Jewish women’s lives after World War II, her immediate response was to urge us to create a volume ourselves, which she helped usher into reality a few years later.

Hasia’s research into the American Jewish experience has great reach, for she has mentored a new generation of scholars dedicated to exploring the complexities and riches of the American Jewish past in colleges, universities, secondary schools and museums located across North America. And we are now mentoring students of our own with the methodologies and creativity of thought that Hasia nurtured in all of us.

Shira Kohn is a member of The Dalton School’s High School History faculty in New York City. She co-edited “A Jewish Feminine Mystique? Jewish Women in Postwar America” (Rutgers University Press, 2010) with Hasia Diner and Rachel Kranson.

Researching history from the bottom up

Hasia always challenged her students to research history from the bottom up. Through expert instruction and the example of her own groundbreaking work, she encouraged us to tackle the central question of social history: How did real, flesh-and-blood, everyday people respond to the forces that shaped their lives?

Following this advice proved challenging as I researched my dissertation-turned-first-book, “Ambivalent Embrace: Jewish Upward Mobility in Postwar America.” I aimed to excavate the anxieties and concerns of American Jews as they experienced rapid upward mobility in the decades after World War II. After all, much of American Jewish life before World War II had been shaped by exclusion and economic instability. While a middle-class lifestyle offered American Jews security and opportunities for innovation, it also tested long-established political affiliations, religious customs and familial patterns. Postwar rabbis and Jewish communal leaders often wondered: Could authentic Jewish life truly thrive in the middle-class suburbs?

While such concerns threaded through rabbinical sermons and scholarly journals in the postwar years, these sources could not tell me much about how Jews without rabbinical or doctoral degrees experienced their upward mobility in the 1950s. Demographic data show us that mid-century American Jews migrated to the suburbs in droves, eagerly opting for the comforts of the middle class. But what evidence could I use to document their possible feelings of ambivalence, loss, or discomfiture?

I struck historical gold in the archives of Congregation Solel, a Reform synagogue established in 1957 in Highland Park, Illinois. Described by its first rabbi as “a Temple for people who didn’t like Temples,” Solel’s congregants preferred to see themselves as intellectual activists rather than well-to-do suburbanites. This caused real tension in the early 1960s as Solel struggled to raise funds for a new synagogue building. In 1963 they vented their frustration in a musical program entitled “Songs to Throw Out Building Solicitors By.” Sung to the tune of “There is Nothing like a Dame,” this song encapsulated their predicament:

There’s lots of books at Solel,

And nothing looks like Solel,

We’ve got guts at Solel,

And some nuts at Solel.

We’ve gone in hock for Solel

Sold our stock for Solel…

We still need dough for our chateau, Solel!

Learning from Hasia’s example and inventive use of sources, I found my people as they worked through the uneasiness of economic change through parody, poetry and the occasional snarky note still tucked away in the basement of the synagogue building that they did, eventually, manage to construct. I am proud to count myself among Hasia’s students, all of whom manage to uncover the everyday humanity of people undergoing tremendous historical change.

Rachel Kranson is director of Jewish Studies and Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Pittsburgh.

In “Roads Taken,” a history of American Jewish peddlers, Hasia Diner took on a subject that “was so ubiquitous that historians almost took it for granted.” Above, David and Harry Silverman in their fruit-peddling cart, Saint Paul, Minnesota, c. 1920. (Jewish Historical Society of the Upper Midwest)

A passionate progressive, a dispassionate historian

Hasia Diner should be celebrated for her tremendous work ethic and productivity. I especially admire Hasia’s willingness and ability to take on the “sacred cows” of American Jewish history. Be they more academic debates like the periodization of American Jewish immigration, or more controversial topics like the American Jewish community’s reaction to the Holocaust, Hasia is peerless and fearless in her determination to challenge conventional wisdom, always with a mountain of archival evidence to prove her point.

What I admire most about Hasia are her principles as a teacher and scholar. In her life outside the academy, Hasia makes her politics plain. But in the classroom and in her scholarly writing, Hasia is careful to maintain a neutral and objective tone. Not all professors agree with this approach, but I have always tried to emulate it. Hasia is a dispassionate historian who, equipped with vast historical knowledge, could be a passionate advocate for progressive causes. Years later, when a student told me they could not ascertain my views on any given issue, I took it as the highest compliment, and I have Hasia to thank. It’s one of the many reasons I am grateful for her mentorship.

On a personal note, Hasia was the one who suggested I turn a seminar paper from a different class into my dissertation which became my first book. She has been supportive of my career ever since, and the careers of all her students, all while writing book after book. Hasia has not only produced an enormous amount of path-breaking scholarship in American Jewish history, she has trained a generation of scholars who aspire to follow in her footsteps, many of whom have already published important work of their own. Her contribution to the field is immeasurable.

David Weinfeld is assistant professor of World Religions at Rowan University in Glassboro, New Jersey. He earned his doctorate in Hebrew and Judaic Studies and History at New York University in 2014, where Hasia Diner was his advisor. He adapted his dissertation into the book, “An American Friendship: Horace Kallen, Alain Locke, and the Development of Cultural Pluralism,” published by Cornell University Press in 2022.

Modeling the traits of a great historian

Hasia Diner’s scholarship and mentorship have transformed the field of American Jewish history.

In the area of research, Hasia reimagines the realm of possibility regarding arguments and sources. She repeatedly asks new questions of seemingly exhaustive topics, where the standard analysis has supposedly left little else for examination. Her book, “We Remember with Reverence and Love: American Jews and the Myth of Silence after the Holocaust, 1945-1962,” astutely underscores the scholarly possibilities when deep archival study and sound methodology can reveal an entirely new paradigm about the study of the past.

Through the research and writing of this book, Hasia has modeled the traits of a great historian. As a mentor, Hasia has helped to define the personal and professional lives of her many former graduate students. I’ll always remember Hasia’s words to me immediately after my NYU doctoral graduation ceremony: “This relationship doesn’t change just because you received your PhD.” True to her word, Hasia continues to serve as a mentor. She offers advice, shares opportunities, challenges assumptions, provides encouragement and serves as a true advocate for her students-turned-colleagues. Beyond influencing the historical discipline, she has influenced the next generation of American Jewish historians. I look forward to continuing to impart Hasia’s many lessons about both the profession and life to my own students.

Amy Weiss is the Maurice Greenberg Chair of Judaic Studies and Assistant Professor of Judaic Studies and History at the University of Hartford.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.