(New York Jewish Week) — Like many New York sports fans of his era, Jeffrey Gurock has a distinct memory related to legendary Jewish broadcaster Marty Glickman.

When Gurock, 74, was growing up, one Sunday morning he and his family made the trek from the Bronx to visit his aunt and uncle in Yorktown Heights, about 50 miles northeast of New York City. The Giants broadcast had been blacked out in his Parkchester neighborhood, but at his aunt and uncle’s house, Gurock was able to pick up the telecast from nearby New Haven.

“But we turned down the sound and listened to Marty Glickman on the radio,” Gurock recalled in an interview with the New York Jewish Week. “He was our story.”

From the late 1940s until the 1990s, Glickman was the voice of New York sports. Glickman spent years as the television and radio broadcaster for just about every New York team, including the Jets, Giants, Knicks and Rangers, plus pre- and post-game coverage of the Yankees and Brooklyn Dodgers. Glickman was the first TV announcer for the NBA, and was also known for his college football broadcasts.

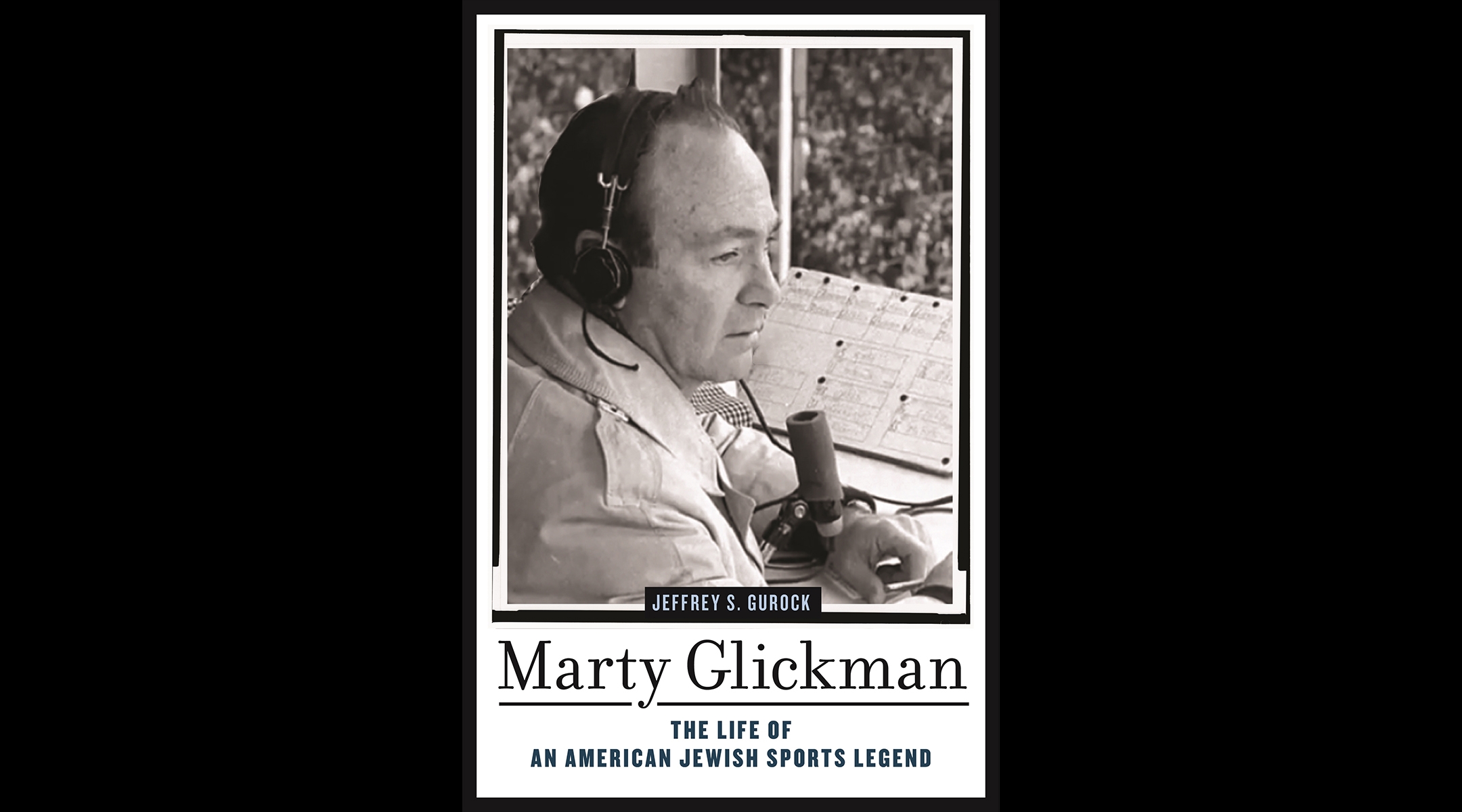

And now Gurock, a historian and professor at Yeshiva University, recently published “Marty Glickman: The Life of an American Jewish Sports Legend” (NYU Press), a book about the beloved sportscaster who died in 2001 at 83.

Gurock, who has written and edited more than two dozen books, including a few about Jews and sports, said his newest work is much more than a sports book.

“The takeaway from the book is the difficulties that second generation Jews have in their chosen field, particularly if they’re in the public eye, to make it, maintain their identity and to avoid the scourges of antisemitism,” he said.

Jeffrey Gurock’s new book, “Marty Glickman: The Life of an American Jewish Sports Legend.” (Courtesy Gurock)

Part of what made Glickman unique, Gurock writes, is the way he spoke to all New Yorkers — Jews and non-Jews alike — in a way that felt personal. He didn’t shy away from his Jewishness, and in fact rebuffed advice that he should change his name to one that sounded less Jewish.

In addition to his classical New York intonation and vernacular, the Flatbush native sprinkled Yiddishisms into his vocabulary, too. “The word choice synthesis was a source of pride to his Jewish listeners, as one of their own integrated sports reporting with their ancestral roots at a time when so many others hid where they came from,” Gurock writes in the book.

Beyond all the games and famous soundbites, Glickman’s legacy is perhaps best illustrated by the number of accomplished broadcasters, many of them also Jewish, who count him as their mentor. Greats like Marv Albert, Ian Eagle and Bob Costas were “disciples” of Glickman’s, as Gurock put it, and some served as Glickman’s proxies as Gurock researched and wrote the book.

One interview stood out above the others, Gurock said: his conversation with NBA Hall of Famer and broadcaster Bill Walton, an Emmy-award winner who has credited Glickman with helping him overcome his stutter. Gurock said Walton told him that Glickman “was the most important person in my life.”

“Why was he so great?” Gurock asked Walton.

“Because I used to stammer, and he taught me how to speak,” Walton said.

Aside from his broadcasting pedigree, Gurock said he was interested in exploring Glickman’s life because of his famous encounter with antisemitism at the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

Before he called games with his signature “Swish!” catchphrase, Glickman was a track and football star at James Madison High School in Brooklyn and Syracuse University, and earned a spot as a sprinter with the U.S. Olympic team as a teenager. Glickman traveled to Germany and trained with the team, only to be inexplicably replaced, along with another Jewish teammate, on the morning of the 400-meter relay.

As Gurock writes in the book, Glickman “was certain that he was egregiously excluded because some American Olympic officials did not want to embarrass Hitler should a Jew end up standing on the victory platform.” (It’s important to note, however, that one of their replacements was Jesse Owens, the African-American runner who in the same games would win four gold medals.)

Glickman rarely spoke about the incident until decades later, when in the 1980s he began sharing his story, including through initiatives with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“I think that Glickman was like most American Jews of that generation, that when you face antisemitism you didn’t confront it head on, particularly when you saw it all around you,” Gurock said. “Then the world changes, the Jewish world changes. In a sense, the Jewish community rediscovers Glickman, and says, look, you have something very important to teach us.”

Despite his infamous benching due to purported bigotry, Glickman would go on to a decorated career in sports. During an era when many Jews struggled to fit in, especially in prominent, public-facing fields, Glickman had a seat at the table, Gurock said. Literally.

“There’s a story of him eating pork chops at the training table” for one of the local teams, Gurock said, noting that Glickman was a secular Jew. “The interesting thing is, he’s at the training table, right?”

In other words, Gurock said, “It’s not whether you win or lose, but whether you’re allowed to play the game.” Or in Glickman’s case, call it.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.