(New York Jewish Week) — In the 1960s, a drag queen named Flawless Sabrina arrived in New York City during a time when drag performances were not only stigmatized in mainstream society, but within LGBTQ circles as well.

But Flawless Sabrina had a plan: Her welcoming demeanor — which she described as a “bar mitzvah mother” — helped her popularize the art form, and over the next few decades she became one of the country’s first well-known drag performers, a prominent LGBTQ activist and a mentor to young queer New Yorkers.

The person behind the drag, the activism and the inspiration was Jack Doroshow, a Jewish boy from Philadelphia who organized his first drag pageant in 1959 as a freshman at the University of Pennsylvania.

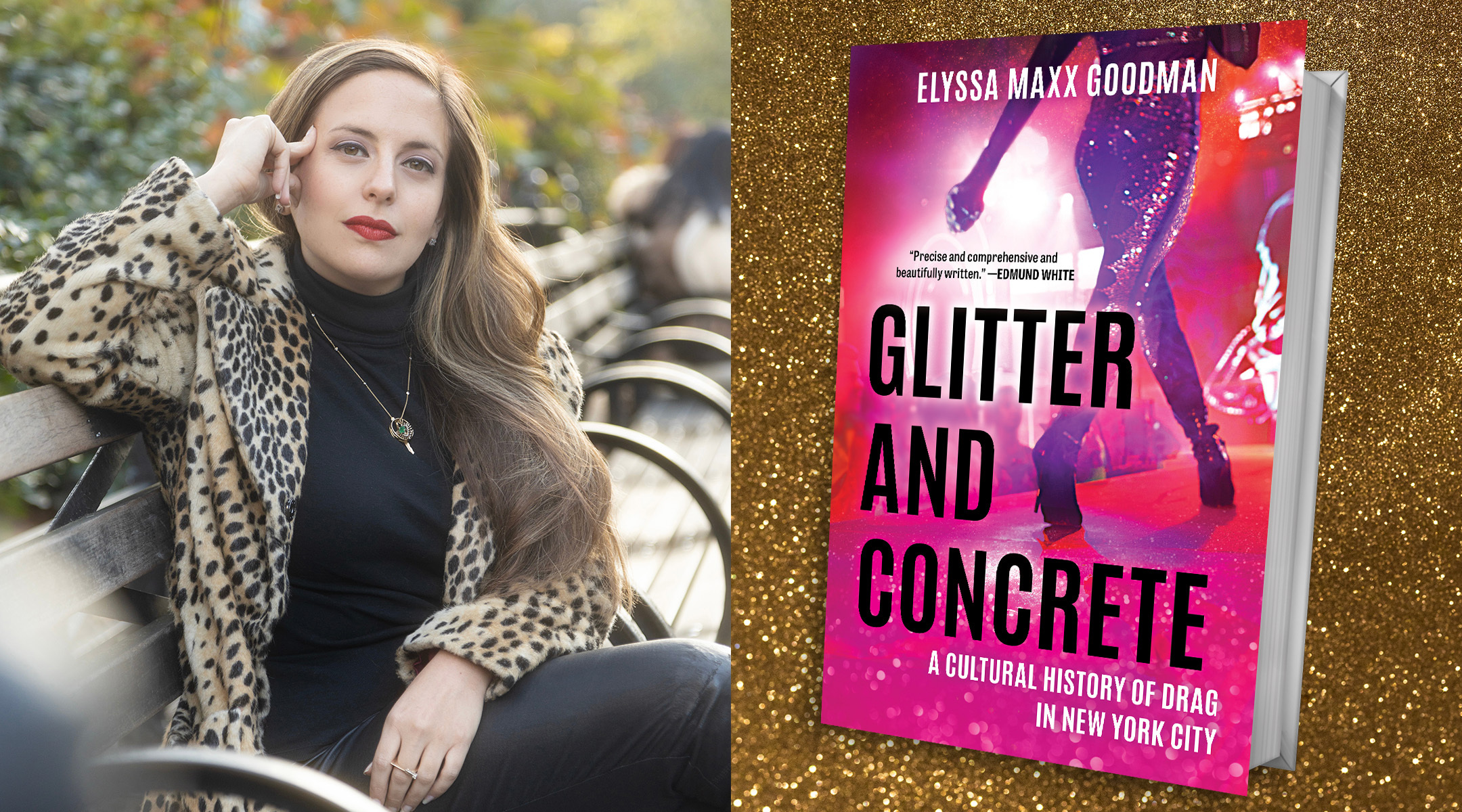

Doroshow’s death in late 2017, at age 78, prompted writer Elyssa Maxx Goodman to think seriously about how to document the history of drag in New York City, a lifelong passion of hers. After more than five years of work, her debut book, “Glitter and Concrete: A Cultural History of Drag in New York City,” is out this week.

Goodman told the New York Jewish Week that it was her Jewish upbringing that made her particularly attuned to recording the stories of these artists and performers over the last 150 years.

“One of the things we learn about as Jews from very young is how our stories either were destroyed or faced many attempts at destruction. That’s something that I kind of took with me throughout my life,” Goodman, 34, told the New York Jewish Week. “I wanted to preserve the stories that aren’t being preserved, which is how I approached my relationship to drag history.”

The New York Jewish Week caught up with Goodman ahead of her book’s launch to talk about how her childhood, New York City and her cultural Jewish identity inspired the book.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The 2021 Drag March at Tompkins Square Park, 27 years after its first iteration in 1994. (Elyssa Maxx Goodman)

What inspired you to write this book?

What pushed me to write this book was that it didn’t exist and it was a book I wanted to read. When the very famous New York drag queen Flawless Sabrina, who was also Jewish, passed away in November 2017, I wanted to make sure that there were no stories that got lost. I started to think about what other books had been written that chronicle the life of drag artists in New York City. There wasn’t a book that was really a written-through history. I knew that these artists deserve that and I wanted to make sure that their stories are remembered. That was definitely the driving force in wanting to do the book.

I first was exposed to drag when I was about 7 years old. I saw the movie “To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar” and I was taken with it ever since then. I had grown up watching 1950s movie musicals with my mother, which were these very vibrant technicolor explosions with lots of swirling dresses and beautiful costumes. Drag is a natural extension of that. So for me, at first, it was just another phase of that interest in costume design and glamor. As I got older, I learned more about the very powerful, rebellious nature of drag and how it is a force to be reckoned with on its own, as an art form and as a life force. What can draw you in is the glamour, but as you get older what keeps you there — at least what kept me there — is the appreciation for its spirit of “Glamour as Resistance,” as the artist Justin Vivian Bond says.

How is your Jewish identity or upbringing connected to your interest in drag?

My relationship to Judaism is deeply cultural — that’s the way that I connect to it most strongly. The first people who brought me to a drag show in real life were my parents and throughout my life, they encouraged my interest in drag.

Everything that we learn about ourselves as a culture, whether it is intentional or not, comes through in creating a book like this, or at least it did for me. We’re taught to question — I arrived at this place because I questioned why the book didn’t exist. Then I just kept asking questions: Where did this come from? Why don’t people know about it? How can I teach it to them? The desire for knowledge and desire for education are all things that I took from Judaism.

The Jewish drag artists I encountered in the book, among them Jack Doroshow, aka Flawless Sabrina, as well as Harvey Fierstein and a drag king named Buddy Kent all came from backgrounds where, in some way or another, they had to fight to be themselves. In some ways, that was fighting to take up space as a Jewish person and in other ways as a queer person. For all of them, it was both. The book contains selections of stories about making space for yourself in the world and the way that you want to live in it — I think that that is something that a lot of Jews had to reckon with as they came to this country in a multitude of ways.

Why did you choose to focus only on the drag history in New York?

New York is one of the cultural epicenters of the world. Because it holds all these different kinds of cultures, it draws the people who are drawn to that. That includes drag artists. There’s amazing drag in other cities, but New York is the city that I know best and it has a history all its own.

It’s also the place that I have the most personal connection to. I’m from South Florida originally and I went to my first drag shows in South Florida, but the drag histories that I learned growing up came from New York. So I moved to New York in July 2010. My primary motivation for moving to New York was to be a writer and to be able to easily access all of the things that I wanted to write about, and drag certainly was one of them. There were these deep-seated histories that had been a passion of mine for a very long time and I wanted to keep telling those stories and learning those stories. New York was a place where I wanted to make myself a student as well as to share my knowledge.

Drag performing has been a major target of right-wing circles this year — as someone who has been involved with and written about the community, how do you respond to the backlash?

I do see it as an opportunity for people to learn more about it. Like I mentioned, drag has been an art form for thousands of years. It’s at least as old as the history of theater. The people who do it are artists and deserve to be respected in such a way. My hope is that with a book that can show the breadth of drag’s involvement in our culture, it can help show that this is an art form with an extended history that can’t just be suppressed and isn’t going anywhere. The struggles the drag is facing are not new, but that doesn’t mean that it should be devalued as an art form, or as a form of self-expression at all.

The New York Jewish Week brings you the stories behind the headlines, keeping you connected to Jewish life in New York. Help sustain the reporting you trust by donating today.