PITTSBURGH (JTA) — I couldn’t walk easily, much less drive, but I knew I needed to be in Pittsburgh the moment I saw a CNN news alert that a shooting had taken place in a synagogue there.

It was Oct. 27, 2018, and I still wasn’t healed after breaking my ankle hiking that summer in Ein Gedi. An old friend was living with us, helping to care for me. Abe Opincar, a former journalist himself, understood what I needed: He agreed to drive me right then from suburban Washington to Pittsburgh.

By the time we got in the car, we understood that 11 people had been killed inside their synagogue. But we knew little more than that. I called Pittsburgh folks on the way, people I knew who had roots in the city, asking where to find sources, what I should know about Squirrel Hill and the Tree of Life synagogue, which was on its way to being known as the site of the worst antisemitic attack in U.S. history.

We parked just off of Murray Avenue on Saturday night just as a havdalah vigil, pegged to the ceremony that ends Shabbat, was getting underway at the junction of Forbes and Murray avenues, catty corner from the JCC. I hobbled into the crowd, seeking out the Jewish teens who had organized the gathering and speaking to the people — Jews and non-Jews alike — who had been drawn to the event.

Attendees huddle at a vigil after the massacre at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Oct. 27, 2018. (Ron Kampeas)

Abe seemed increasingly agitated, grimacing at me whenever we exchanged glances. When the crowd started singing hopeful songs — such as “How Good and Pleasant it is for a Tribe of Brothers to Live Together in Harmony,” a verse from Psalms that is a Christian hymn — he rolled his eyes.

When the vigil was done, we got seats at a local restaurant. As we bolted down plates of warmed-over meatloaf, I read aloud a couple of quotes from my notebook. Abe scoffed at the pledges of hope and renewal and strength. Communities just don’t recover from a shooting like this, he said.

I had my own doubts. But I also had a responsibility to tell the day’s story. You’re probably right, I told Abe, but I can only go on what the people I interview tell me. If they’re lying to themselves, so be it.

And then I filed and I waited for edits and it was done and we headed to the car and just as we got there I got a call. I didn’t say much out loud — it might have just been “Oh my,” or just “Oh,” and it might have been the way I said it, but Abe asked what I had learned. I hesitated and he said, as I twisted into the passenger seat, pulling in my cursed ankle, “You have to tell me.”

That was a source, I said. The shomrim, the men and women who keep company with Jewish dead until they are buried, are waiting outside the synagogue. The feds won’t let them remove the bodies for care until they finish combing the crime scene.

Abe started wailing. He was banging his palm on top of the rental car, letting out the despair that I, too, felt, knowing that the Pittsburgh Jewish dead were alone and uncared for, in contravention of the deepest and oldest rituals of our shattered people.

I did not need his tsunami of grief. I just needed him to drive to our dump of a motel on Pittsburgh’s outskirts, the only thing available because there was a big football game in a football crazy town the next day, the day after a gunman killed 11 Jewish worshippers. I looked around at the turn-of-the-last century houses behind the trees and prayed that a window would not light up.

I had to think. Should I try to publish a story from my car about what I had just learned? Was my source solid enough, or did I need to confirm it? I did not need grief clouding the logistics that bring stories to readers.

In the end, I confirmed the news and included the interview in the next day’s story. But in that moment, I was furious with Abe and furious with myself, at whatever there was in my expression that, even through the dark of night across the distance of a car, made Abe able to tell that the call had delivered a punch to my gut.

Dor Hadash congregants meet at East Liberty Presbyterian Church the day after a gunman massacred 11 worshipers at the synagogue where they usually congregated, in Pittsburgh, Oct. 28, 2018. (Ron Kampeas)

The next day, Abe’s anxious, skeptical outlook was vindicated, to an extent. The victims, the residents of Pittsburgh, seemed less sure of the strength they had projected the evening before. The folks peddling bromides about standing together, including Israel’s Diaspora minister, Naftali Bennett, came across as clumsy. There was less certainty that Pittsburgh would ever overcome the massacre of innocents at prayer.

“What do you do to make sure that fear doesn’t prevail?” the city’s Chabad rabbi, Yisroel Rosenfeld, asked me.

“I couldn’t see the city anymore,” said Wasiullah Mohamed, the executive director of the Islamic Center of Pittsburgh, which had allied with the city’s Jewish community on multiple occasions. “I could just see its dark corners.”

I tried to talk to congregants of the three congregations housed in Tree of Life, Tree of Life-Or L’Simcha, New Light and Dor Hadash — but they had undergone the transformation I have seen at other scenes of horror, from verbose within hours of the attack to unwilling to engage within a day or so.

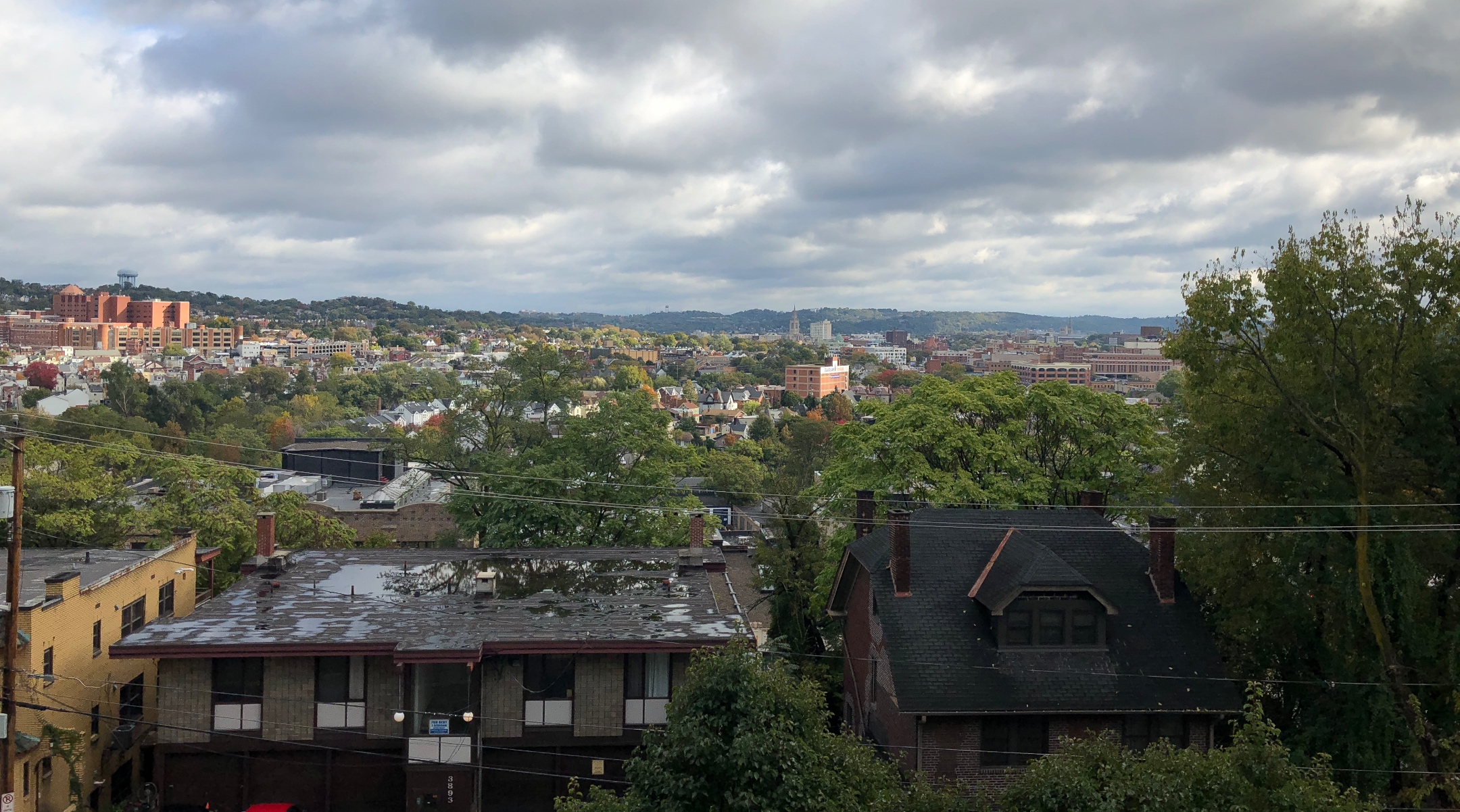

Leaving Pittsburgh, Oct. 29, 2018. (Ron Kampeas)

Two years later, covering the 2020 election in Pittsburgh, I found a community as cloistered as it had been when I left after the massacre, an insularity codified in a new counseling service called the 10.27 Healing Partnership. I got fantastic insights from Maggie Feinstein, the service’s founder, but it was clear I was not going to speak to the traumatized folks she was counseling. They were off-limits.

Voters line up outside a voting place in a synagogue Shaare Torah, on Election Day in Pittsburgh, Nov. 3, 2020. (Ron Kampeas)

In April, when the trial was ready to go ahead after four and a half years of waiting, it was even more formalized. The 10.27 Healing Partnership had hired a PR agency to clear all interviews, and even those who did speak, mostly lay leaders of the congregations, seemed to be working from a script, with bromides about doubling down on commitment to Jewish values.

I returned to Pittsburgh for the first day of the trial on my own — with my ankle long healed, I didn’t need Abe or anyone else to accompany me. Pittsburgh’s charms made it easy: The rich Italian-influenced cuisine, the parks, the cityscape set against three rivers and a mountain range. But the coverage was trying. I got a hotel room just a seven-minute walk from the austere mid-20th century federal courthouse, and I was walking distance from Market Square, which was buzzing throughout the summer with buskers and diners and drinkers, but I preferred the sterile comforts of my room, falling asleep to comfort TV, sitcoms and ancient movies.

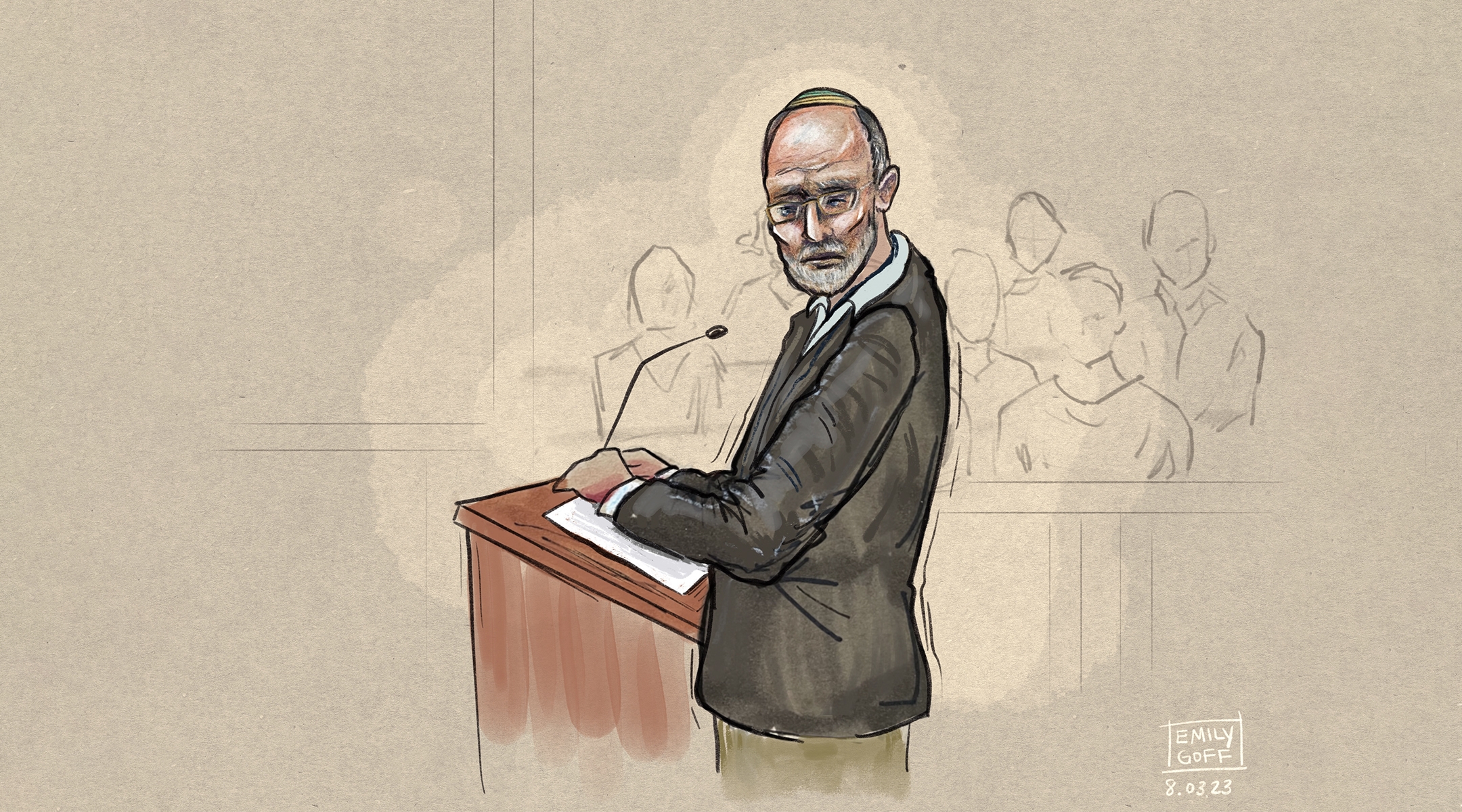

A portrait of the writer by sketch artist Emily Goff. (©Emily N Goff, 2023, all rights reserved.)

I did most of my reporting from a media overflow room: There were only 10 slots in the courtroom for media, and the reporters agreed at the outset that seven should go to local media — one to the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle — and three to national media. We watched large flat-screen TVs streaming in the proceedings from the courtroom four floors above us. We were not allowed to take pictures or use recording devices, not our phones, not our laptops, even in the overflow room. We could only type into our laptops, and if we were in court, write onto notepads.

The skills I acquired decades ago as an Associated Press reporter in Jerusalem, taking dictation from two or three sources (a radio, a TV, a spokesman on the phone) at once unrusted themselves after years of one-on-one interviews and more recently AI transcription. I typed as fast as I could.

Whatever pretense of competition the journalists thought they brought into the media room soon slipped away as we shared information with each other, both about details we missed in the trial itself and about what the reactions were in the courtroom. Did the defendant look at the witness? Which lawyer objected?

I relied on locals for Pittsburgh information and I became one of the designated Jews in the room, at one point explaining to a TV producer what a tallit was — the prayer shawl that Bernice Simon used to stanch her husband Sylvan’s wound, before the gunman shot her.

The radio guy who assiduously tracked down every scriptural reference looked up at me quizzically when Dan Leger, one of two shooting victims who survived, said, “There is no way to understand the tranquility of those who do wrong, and the suffering of those who do good.”

I explained Pirkei Avot, the Ethics of the Fathers, which functions as a go-to source for an apt Jewish quote.

That spirit of cooperation was exemplified by the alliance forged by the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle, and the striking journalists from the Pittsburgh Post Gazette, who had launched an online alternative news source, the Pittsburgh Union Progress. They collaborated to share color, context and expertise not to just with each other but with the others covering the trial.

Comfort food consumed at the Union Grill in Pittsburgh, Oct. 28, 2018. (Ron Kampeas)

It was when the trial was fully underway that the local Jewish community’s filters were removed. On the witness stand, the survivors, the families of the dead, unleashed their accumulated grief and described in vivid detail the horrors they encountered, under the gentle solication of the prosecutors.

The second day of the trial, I listened, rapt, to the testimony of Carol Black, who survived by hiding during the shooting and whose brother, Richard Gottfried, was one of the fatalities. More than her recounting of the grim details of the day, how she came to be in the New Light sanctuary riveted me.

I had that epiphany every reporter longs for, of a story bigger than the sum of its already major elements. Black’s testimony and the testimony of others told the story not just of a single horrific day, but of American Jews, and how they worship and gather and stay together.

She and her brother were leaders at the New Light congregation, and she loved calling congregants up to read the Torah. Richard became more religious after their father died 30 years ago; Carol joined him in the middle of the last decade after a hip injury cut short her favored Saturday morning activity, running. She became bat mitzvah as an adult because the family’s congregation when she was growing up in nearby Uniontown did not mark the coming of age of girls. When she heard the gunfire, she was unzipping her tallit bag.

Leger explained the origins of Reconstructionism, perhaps the most American of Jewish denominations founded in the last century by Mordecai Kaplan, who sought to reconcile the American ethos of personal freedom with Jewish worship. Witness after witness, especially those from Leger’s Dor Hadash congregation, explained the Jewish imperative of welcoming the stranger.

When the gunman blew out the glass doors of the synagogue on Oct. 27, 2018, two American Jewish stories collided: One of open, proud practice and one of terror of what lurks among one’s neighbors.

The gunman’s trajectory was also an American Jewish story, and the malign role Jews have played in this country’s white supremacist imagination, from Henry Ford through David Duke through Charlottesville. He read about Dor Hadash’s partnership with HIAS, the Jewish immigration advocacy group, and he embraced the antisemitic trope that Jews were funding an influx of people of color to kill and replace whites.

He found the antisemitic “great replacement theory” online drawing from sources that placed it in the context of the American immigration debate, peddled by, among other, the president at the time, Donald Trump. He found succor on the Gab social media site, founded in Pennsylvania to counter the censorship the far right was running up against on normative social media sites after Trump’s election. On Gab, he engaged 400 times with posts featuring the word “kike,” considered by some historians to be a uniquely American slur.

The defense’s argument, that the gunman’s very antisemitism proved that he was delusional, was itself delusional, in a very American sense: How could the land of the free, of opportunity, accommodate a narrative about Jews as spawn of Satan?

The story was getting under my skin, under the skin of other reporters in the room. During a break, I flew to Wisconsin for parents day at my son’s Jewish summer camp. My wife and I drove down long roads skirting 18 wheelers like the one the gunman drove, past small family bakeries like the one where he lived and worked for 14 years, and I wondered about his American story, and how welcome I would be in the homes and businesses around me.

I caught myself: How unprofessional. You’re a journalist, professionally bound to maintain distance. Not everything is personal.

And yet when Andrea Wedner, who was shot and who saw her mother, Rose Mallinger, 97, die, described how she left as a first responder led her away — “I kissed my fingers and I touched my fingers to her skin. “I cried out, ‘Mommy’” — I looked away to control myself. I saw another reporter across from me, weeping.

Years ago, in far-flung bars and cafes, after days spent covering revolution, wars and riots, I’d heard foreign correspondents claim to have mastered the art of not getting caught up in the emotions that swirled around a conflict. I understood the value of keeping oneself apart from one’s subjects. A good reporter does not cut off his emotions, but he does not indulge them either. He keeps them at a reserve like oils on a palette, to be applied judiciously.

Pittsburgh Jewish Federation CEO Jeff Finkelstein speaks to the press after a jury find the gunman who shot 11 Jewish worshipers guilty of federal crimes. The writer kneels at lower left=, in Pittsburgh, June 16, 2023. (Alexandra Wimley/Pittsburgh Union Progress via Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle)

There were three verdicts delivered during the trial: one determining the gunman’s guilt, one determining whether the crimes were eligible for the death penalty and one determining whether the gunman deserved the death penalty.

The sides delivered closing arguments two weeks ago. The lead prosecutor, U.S. Attorney Eric Olshan, finished his presentation with a slide show of the corpses of the 11 in place at the synagogue.

“Joyce Fienberg, her loss alone is sufficient to justify a sentence of death,” Olshan said, and he proceeded, attaching the same assessment to the other 10 names: Richard Gottfried, Rose Mallinger, Jerry Rabinowitz, Cecil Rosenthal, David Rosenthal, Bernice Simon, Sylvan Simon, Daniel Stein, Melvin Wax and Irving Younger.

With each name, a slide appeared: a ruined body cradled by the cold white light generated by a flash. Outside, I thought, the shomrim waited for hours in the October chill, until the FBI told them to go home, that they would call when it was time.

“He turned an ordinary Jewish Sabbath into the worst antisemitic mass shooting in U.S. history and he is proud of it,” Olshan said.

The jury asked a couple of questions, and the next day, after seven hours of deliberation, they delivered their verdict: Death.

The victims and their families were ready to talk. They gathered for the media at the Jewish community center. Their message echoed that of the vigil on the evening of Oct. 27, 2018: Resilience. Hope. An American Jewish story.

“This fair judicial process is a reminder that we belong here,” said Howard Fienberg, whose brother Anthony dedicated a Torah in their mother’s memory just three days earlier. “This is where we are. This is where we’ve been. And this country is where we belong. And we remain a part of it. We always will.”

The JCC shut down at 7 p.m. Outside, on Forbes street, a single TV reporter caught the last light of day for one more standup.

An hour or so later, I was at the Murray Avenue Grill, just a block away from where I’d dined with Abe. It was packed. No one was talking about the trial, not even the local city council member I’d interviewed earlier in the day. A couple of tables were bursting with pink and with giddy anticipation of “Barbie,” playing across the street.

The next day, Judge Robert Colville convened the court one last time to formally deliver the death sentence, first asking the families to deliver impact statements. Twenty-three people spoke, raining fury down on the gunman, often expressed as a determination to outlive him, for generations.

Michele Rosenthal, whose brothers, Cecil and David, were among the fatalities, said her family had never thought much about immigration. The gunman changed that.

“We are resolved from here, on every Oct. 27, our family will make a donation to an immigrant organization such as HIAS,” she said. “We will mail the receipt to [the gunman’s] new home wherever that may be.”

Dan Leger who was shot in the 2018 Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, gives a victim impact statement in the Joseph Weis bFederal Courthouse in Pittsburgh, Aug. 3, 2023. (©Emily N Goff, 2023, all rights reserved.)

Survivors described a grief that was at once wild with motion and immutable. “The past four and a half years have disrupted relationships, wasted millions of dollars and left empty places in our hearts and homes,” said Dan Leger. “It has moved some to become vengeful and experience hate themselves. It has moved people to form friendships …. To appreciate the fragility and beauty of life on earth.”

Colville thanked the witnesses, the defense and prosecution and the jurors. When it came to the victims, he borrowed a Jewish expression.

“May their memory be a blessing,” he said before finalizing the death sentence.

I said goodbye to the reporters, to the courthouse staff, to Emily Goff, the courtroom artist who filled her breaks by sketching us in the media room. By 2 p.m., the courthouse was empty. I had a room for a night in Pittsburgh, but I couldn’t take another hour, much as I had come to love the city and its bridges and its clusters of homes and buildings set against the Allegheny Mountains.

I wanted to see Baldwin, where the gunman grew up, the setting for the Christmastime photos the defense threw up on screens to humanize him. I had driven close by every time I’d come and gone to Pittsburgh but had never made the detour.

On the way, I drove through Whitehall, a suburb where utility poles are festooned with flags saluting the town’s veterans, many of them young men who had set out after 1941 to defend the world from fascism.

There was nothing in Baldwin’s duplexes and flat brown apartment buildings, its Italian eateries, its strip malls that explained anything.

Waze took me onto Route 40, which was as empty as the starless sky. I stopped to buy almond bark for my wife from Gene and Boots, a candy store that stood alone on the highway and that sells a milk chocolate pistol with two chocolate bullets. I gassed up at a sporting goods store.

I pulled up to my house close to midnight Thursday. I looked at my phone. No alerts, no Slacks from editors. There was a single text message from my son’s counselor at his camp, deep inside Wisconsin’s north country. My son had won the camp’s Derech Eretz award because he was “compassionate and kind.”

I had no idea the camp had a Derech Eretz award. So I wept, finally.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.