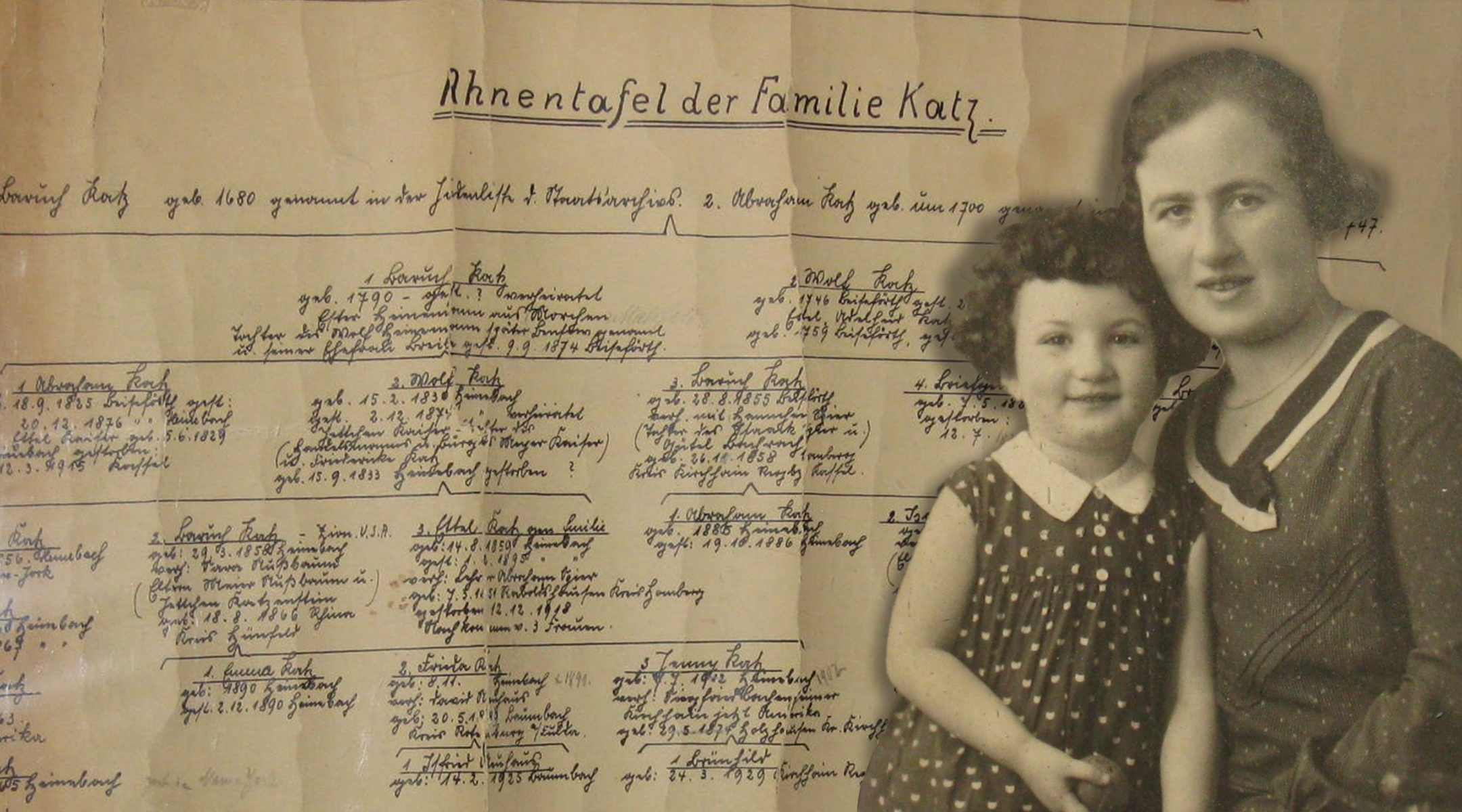

(JTA) — It was an astonishing and revelatory moment: I’d started exploring my family’s genealogy in the 1970s, and my grandmother mentioned that a cousin of her father Baruch had hired a professional researcher in 1930 to create a family tree. The cousin’s widow was still alive, and she gave me the document, written in old German script.

My great-grandfather Baruch Katz was born in the 1850s and incredibly was still with us in 1953, when I was born. Having known him, it was therefore with intense interest that my mother and I perused the “Ahnentafel,” the Katz “ancestor table.” The first named ancestor was from 1680, and when we reached the bottom of the chart, my mom pointed and gasped “That’s me!” She was born in 1929 and was the final entry in the nearly 250-year family saga.

But there was more. The researcher, citing information from the local registrar’s office as well as the Prussian State Archives, wrote that the Katz family had not only lived in their village of Heinebach for more than 300 years, but had roots in the general area dating back to the years 1150–1200.

The discovery that my family had been in the region that ultimately became Germany for nearly 900 years was a decisive factor in a personal milestone event that occurred just last month. Despite having lived most of my life within five blocks of the Long Island Expressway, I became a citizen of “Bundesrepublik Deutschland,” the Federal Republic of Germany.

I should emphasize that the dismay I first felt as a child hearing stories about relatives wiped out in the Holocaust has only increased exponentially over my lifetime. As a teenager, my father’s surviving cousin in Israel told me everything he knew about the fates of his parents and siblings, and as a journalist in my 20s, I began reporting on survivors and broadcasting their grim stories. In the 1990s, I became an interviewer for Steven Spielberg’s USC Shoah Foundation, and the nightmarish tales I heard from dozens of survivors are seared into my memory. My loathing of Nazi Germany and its collaborators knows no bounds.

And yet, shortly before the 2020 presidential election, my family and I had a sober discussion about what we might do if Donald Trump were to be re-elected, or if he staged a coup. We were convinced he had opened the floodgates to racism and antisemitism, to synagogue massacres, book-banning, voter suppression and various hallmarks of authoritarianism. I have no children, but my sister and niece are both married to Israeli-Americans, and we all have deep ties to Israel. Moving there, if it ever became necessary, would be our first choice.

It was at that moment the “German citizenship lightbulb” went on in my head. Our troubled past teaches us that Jews need as many options as possible, I argued, and recent changes in German law put citizenship within reach. Regaining that status would correct an historic injustice. In addition, during my five visits to the country, I had met countless Germans born after the Holocaust who were sincerely grappling with their country’s horrific history, and were determined to somehow “heal the wounds of that dreadful time,” as one official put it.

Author Steve North, right, accepts German citizenship from Germany’s Consul General in New York, David Gill, in New York City, May 2023. (Courtesy Steve North)

I’m far from alone in regaining German citizenship of the past due to alarming political events of the present. Attorney Stephan Heidenhain, who represents clients in the midst of the process, told me he credits upticks in applications from the United Kingdom to “the Brexit effect, and from the U.S. because of the Trump effect, and from Israel since late last year to the Netanyahu effect,” a reference to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s extreme right-wing government and its proposal to reform the judiciary in ways that its critics call undemocratic.

Between “Heimat” and Washington Heights

My mother, born Brunhilde Bachenheimer in the city of Marburg; her parents, Jenny and Siegfried Bachenheimer; and my mother’s grandparents, Baruch and Sara Katz, managed to escape Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Opa Baruch headed the Jewish community in Heinebach, and much of the Nazi activity after Hitler’s rise to power was directed at his home. A full year of vicious attacks on the house — to which my mother and grandparents had moved after the Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses left them penniless — convinced Baruch he should accept an offer of assistance and sponsorship from his younger brothers, who had emigrated to New York decades earlier. The family eventually boarded the SS Bremen and sailed away from their Heimat, their homeland.

My father’s family story was quite different. His parents left Poland for New York around 1912 but stayed in contact with the relatives who remained in Warsaw and Lodz. In the years following the Nazi invasion of 1939, my paternal grandfather’s two sisters, their husbands, and 10 of their 12 children were murdered in the Holocaust, while my grandmother’s aunts, uncles and many cousins were among the martyred six million.

Consequently, my sister Susan and I grew up detesting Germany, knowing we should not buy anything made there, and certain we’d never set foot in that abhorrent, blood-soaked land from where such evil and brutality had emanated.

Why, then, am I now a dual citizen of both the U.S. and Germany? In 1941, Hitler stripped all Jewish Germans of their citizenship, no matter where they were in the world. My grandparents became naturalized Americans that year, but my mother — although living happily in the Bronx — was stateless for a decade, until applying for U.S. citizenship when she turned 21.

Four years after the collapse of the Third Reich, Article 116 of Germany’s post-war constitution allowed for the restoration of citizenship to German-born Jews and their descendants. In 2019 and again in 2021, the German parliament amended the law to remove various quirks and obstacles that had complicated the process for many, including other victims of Nazi persecution.

During my childhood, the only official link to Germany was the monthly check my Oma Jenny would receive from the Deutsche Bundesbank — a part of “Wiedergutmachung,” or reparations.

German culture, however, remained a component of our lives. German was the language spoken in the Washington Heights apartment my widowed grandmother shared with her sister and brother-in-law, neither of whom ever learned English. When I was six years old, Oma bought a record and book set for me that taught German to children, and my sister and I delighted in Oma’s repeated recitals of the popular children’s poem, “Hoppe, hoppe reiter.” My mother, an expert baker, often created German pastries such as Apfelkuchen, Pflaumenkuchen and Mandeltorte, and while she largely avoided speaking German except when necessary, I remember her and a friend once joyfully breaking into a song from their childhood, “In Lauterbach hab’ ich mein Strumpf verlor’n” (“I lost my sock in Lauterbach!“).

A bittersweet return

Despite the warm connection to part of our German heritage, the idea of actually visiting the country remained verboten until 1983, when a group there invited my mother for an all-expense-paid trip to her hometown; the stated goal was to show that modern Germany was dramatically different than it had been during the Third Reich. After much debate, my parents and I accepted the invitation and had a bittersweet, cathartic experience. My mom’s now-elderly former neighbors greeted her as if their own child had shown up after half a century, and for me, at age 30, the legend had finally become reality. I felt oddly at home standing in the towns where my family had thrived, and visiting the graves of my ancestors. We also, however, felt obliged to make a chilling visit to Dachau.

Steve North, at left, with Marburg Burgermeister Franz Kahle, North’s mother Bunny (Brunhilde) North and her grandchildren Talia and Aviv Gilboa, at Marburg City Hall in 2009. (Courtesy Steve North)

In 2009, to mark her 80th birthday, my mother agreed to return once more, in order to show her then-teenaged grandchildren, Talia and Aviv Gilboa, where she had been born and why the family had fled Germany. Incredibly, there still was a Nazi right next door: a neighbor who had beaten up my grandfather’s young cousin, before she and her parents were deported to their deaths. (We confronted him, and he denied everything and died the next year.)

We visited one cemetery where I took a picture of my nephew standing next to the gravestone of his five-times-great-grandfather, born in 1767, and I gave a speech to a high school class at the Jakob Grimm Schule in Rotenburg. I assured the students they bore no guilt over what their grandparents might have done — but told them they needed to realize their special responsibility to fight racism and Jew-hatred.

I had begun to feel more comfortable being in Germany and made three other trips there. My mother died in early 2019, and several months later, I was once again in Heinebach, this time to install “Stolpersteine,” the small brass plaques that are embedded in sidewalks in front of homes where Jews once lived, with their names and fates inscribed upon them.

I wanted to support the efforts of today’s good-hearted Germans who are dealing with their past, and I view the restoration of citizenship as a piece of the overall puzzle, which includes reparations, aid to Israel, visits for German-born Jews to “the new Germany,” Stolpersteine, the ubiquitous Holocaust memorials and the creation of Berlin’s Jewish Museum.

I thought of philosopher and Holocaust survivor Emil Fackenheim, who wrote in 1972 that the “commanding voice of Auschwitz” means Jews are forbidden to hand Hitler posthumous victories. In my mind, regaining citizenship takes that notion a step further: it hands Hitler a posthumous defeat. I decided to begin the process, and my nephew — whose college paper was about the concept of reparations — agreed to join me. As Aviv explained, “Countries that commit crimes against humanity rarely admit responsibility and are even less likely to take meaningful steps to atone for those crimes. Germany is one of the few countries that has done both.”

It is, clearly, the ultimate irony that we might view the nation that so eagerly would have killed my mother as a potential refuge from a possible future autocratic government in America. Although I have always argued that nothing and no one should be compared to Hitler and the Nazis, I could not disregard the voice of my mom’s cousin Ruth, who is now nearly 103. She escaped Germany in 1940, while her mother remained behind and was murdered. In 2016, Ruth said to me “When I hear Trump, I hear Hitler again. When I see his rallies, I see the Nazis again.” Her views since then have not changed, and we ignore the words of one of the final eyewitnesses at our own peril.

An intense debate

Nearly any kind of rapprochement with Germany sparks intense debate within the global German-Jewish community. A resident of England wrote on social media, “Any British person who applies for German citizenship is effectively forgiving Germany for the Shoah” (the Hebrew word for Holocaust).

I requested comments on the subject from two appropriate Facebook groups and was flooded with heartfelt emails, both pro and con. (Some requested that I only use their first names, an indication of the extent of the ambivalence and controversy.) Monica — whose father survived Dachau and whose grandparents were murdered — said, “I’ve accepted Germany’s offer of citizenship because I believe every Jew should have a second passport — and, because Germany has, more than any other country, faced its past. That doesn’t mean I’m not conflicted.”

Vera Meyer, who created a Facebook page for “yekkes,” as some German-speaking Jews came to be known in Israel and elsewhere, said gaining the citizenship “felt like I had, on a very miniscule level, helped to undo the injustice done to my parents of having robbed them of their birthright,” adding “I think it’s important to recognize that today’s Germans have suffered from bearing the brunt of their ancestors’ past. I always say, ‘we both feel pain — we as descendants of victims, you as descendants of perpetrators. Pain is pain, so let’s try and heal together.’”

My cousin Stewart Florsheim was adamant for decades about not visiting Germany, saying “I did not want to support anything that would even begin to relieve the Germans of their accountability.” Last year, however, after receiving an invitation to participate in the installation of Stolpersteine outside his mother’s former home, he reluctantly agreed to the trip — which altered his long-held opinion in a profound way. “I was deeply touched by some of the Germans I met,” he said, “who all expressed a deep, honest remorse.” Since then, he has regained the citizenship that both his parents once held.

Linda is also the child of two German-born survivors, and the entire subject infuriates her. While acknowledging that “some Germans are sincere in their efforts to make amends,” and “it’s hard to be critical of the government’s efforts at Holocaust education,” she believes it’s all motivated by guilt. Nothing, she insists, “can change or make up for the fact that Germany engaged in state-sponsored murder, torture, kidnapping, deprivation, robbery and countless other atrocities against Jews, including my own family. Ordinary Germans made it possible by looking the other way. Antisemitism runs deep. Young Germans today may claim they have nothing to do with the Holocaust. But values and prejudices are passed down through the generations. As far as I’m concerned, every single German is suspect. I wouldn’t give Germany the honor of my citizenship. They took it away. Now they can shove it.”

“A Germany I feel comfortable with”

I fully agree that nothing Germany does can “make up” for its despicable history, and every German official I’ve spoken with asserts that point. Even during our first trip in 1983, one Burgermeister conceded that the word for reparations, “Wiedergutmachung” — which literally means “making things good again” — was a misnomer, as nothing can ever be “good again” for the millions who suffered and died. But, they have told me, the futility of fully righting the wrongs should not prevent Germany from every effort, however symbolic, to address the past. As Germany’s then-Interior Minister Horst Seehofer said after the citizenship law was amended, “This is not just about putting things right. It is about apologizing in profound shame.”

A view of some “Stolpersteine,” or memorial “stumbling blocks” with the names of the Nazis’ victims, in Berlin, Aug. 2012. (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

I choose to remember the German who approached my niece and nephew in 2009, after a ceremony affixing a plaque to the former synagogue in one of our ancestral villages. “I want you young people to know we are not the same as our grandparents who did these things,” he said. “Please, please remember that.” I think of the high school teacher in the village of Kirchhain, where my mother spent the first four years of her life before having to move to her grandparents’ home in Heinebach. When I requested help translating century-old recipes written by my great-grandmother, the teacher enlisted two students who spent many weeks deciphering the handwriting, telling me it was part of their continuing education about the Jewish life in their town that had been eradicated.

I think of Professor Heinrich Nuhn, who has dedicated his career to teaching young Germans about the Jewish presence in the state of Hesse, and who mapped out the locations of a dozen graves of my ancestors, dating back to the 1700s.

All these people — and many more — were the guides on my pathway to reclaiming German citizenship, which officially happened during a private meeting with Germany’s consul general in New York, David Gill. To my surprise, he said that giving me my naturalization papers “feels wonderful, because we Germans get part of our history back. It reminds us how much knowledge and wisdom was lost” by expelling and murdering the Jews. He spoke of handing the documents to a 97-year-old Hamburg-born woman who said it gave her closure, and of repatriating a 95-year-old man who told him “the Germany of today is a Germany I feel comfortable with.”

I’m not sure I could ever feel fully comfortable with Germany, and I have no plans to leave the United States anytime soon; for me, becoming a German citizen was a symbolic gesture. On the other hand, the unthinkable happened in a supposedly civilized country in modern times, and it would be foolish to disregard the possibility of history repeating itself here, given the Jew-hatred we constantly see expressed on both the extreme right and left of the American political spectrum.

I subscribe to the Jewish concepts of “teshuvah,” repentance, and “tikkun olam,” repairing the world. And I wholeheartedly believe the restoration of citizenship is equivalent to giving the finger to Hitler and his henchmen, while simultaneously accepting the hand of modern Germans, offered in the spirit of friendship, remorse and reconciliation.

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.