(JTA) – Among the many books that conservative parents have recently asked their children’s schools to remove is a lushly illustrated version of the most famous Holocaust diary.

The graphic adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary, published in English in 2018, has found itself at the center of a growing number of controversies involving book removals from school libraries. A small number of passionate activists have pushed for the book to be removed from schools in Florida and Texas, calling it “pornography” and even “antisemitic.” Sometimes, they’ve succeeded.

The movement to police children’s literature — particularly graphic novels — on the basis of race, sex and gender has encompassed thousands of different titles, and it has grown to become a potent political force with potential reverberations for the 2024 presidential race. The official who has played one of the biggest roles in enabling parents to challenge school library books, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, is now running for president.

To defenders of the illustrated book — including the foundation created in Frank’s memory, historians and Jewish groups — the inclusion of Anne Frank’s diary among the list of banned books is a sign that the movement is bigoted and misguided.

Proponents of removing the book from schools say the graphic adaptation is essentially an obscene version that distorts Frank’s legacy and aids in “grooming” children. Even some Jewish parents and at least one Jewish lawmaker have objected to the book’s presence in schools.

“I read the diary of Anne Frank many times as a kid. I don’t remember any of that stuff that they put in that graphic novel,” Florida Rep. Randy Fine told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Calling the adaptation an “Anne Frank pornography book,” Fine continued, “And frankly that graphic novel is antisemitic. To sexualize the diary of Anne Frank in that sort of inappropriate way, it is antisemitic.”

Here is what you need to know about the book, the criticism it’s facing and the context that has made it a flashpoint in a deepening culture war.

What is ‘Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation’?

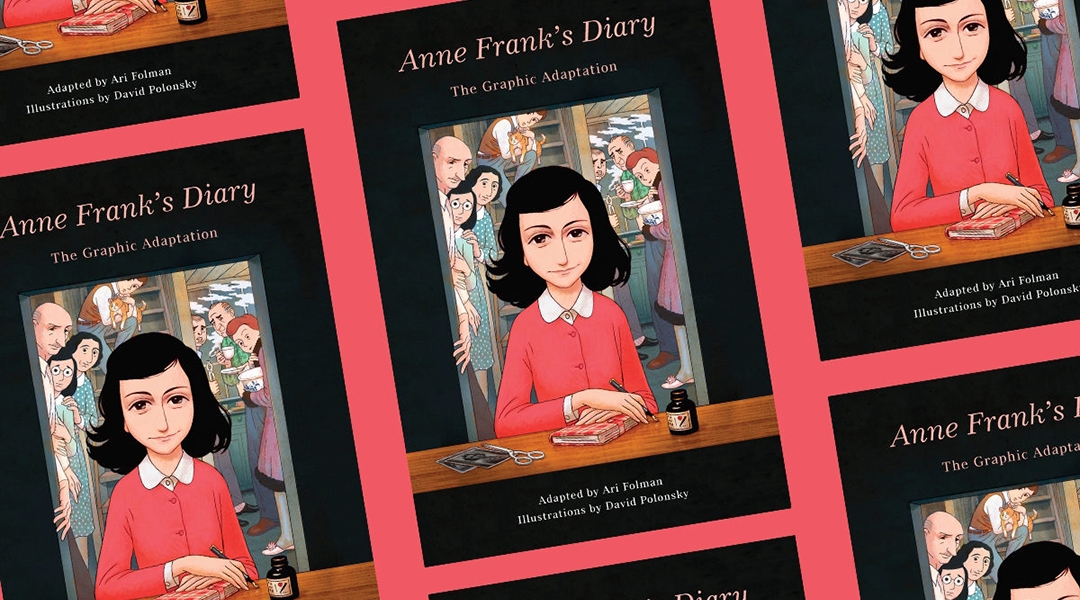

Published in 2018, “Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation” is a new, abridged version of Frank’s famous diary presented in comic-book format. The project was authorized by the Anne Frank Fonds, the Switzerland-based foundation started by Anne’s father Otto Frank, which controls the copyright to the diary Otto rescued after he survived the Holocaust. Anne herself perished in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp after hiding out for most of the war with her family in an Amsterdam annex.

The Oscar-nominated Israeli filmmaker Ari Folman, together with illustrator David Polonsky, put the new book together. It was intended as a companion piece to the 2021 animated film “Where Is Anne Frank,” which Folman directed.

While the film tells the fanciful story of Anne’s imaginary friend Kitty coming to life and wandering through modern-day Amsterdam, the book is a straightforward, though heavily truncated, rendition of Anne’s original diary. All of the entries it reproduces are taken from her original text, and dialogue between the characters in the annex is based on Anne’s own recollections of their conversations. Some of its supporters resist the label “graphic novel,” which they say implies the story is fictional.

The new book, the foundation says, is not meant to replace Frank’s original diary, first published in Dutch in 1947 as “The Secret Annex” and in English in 1952 as “The Diary of a Young Girl.” That book, along with subsequent editions that restored some passages edited out of the first publication, continues to be published and widely read in dozens of languages.

Why and how is the book being challenged?

A handful of parent activists, the largest “parents’ rights” group in the country and at least one Republican state lawmaker — Fine — have specifically gone after “Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation” as part of their larger campaign against what they say is obscene and pornographic content in schools. After a few isolated incidents of parental opposition to the book over the last year, their efforts have gained steam in recent months.

Organized by members of “parents’ rights” groups such as Moms for Liberty and No Left Turn in Education, parents nationwide have brought challenges against thousands of books in school libraries, the vast majority of which deal with topics of race, gender and sexuality. This movement began as parents organized to oppose COVID-19 mask mandates in public schools, and picked up steam in the aftermath of the 2020 racial justice protests following George Floyd’s murder, as well as recent political controversies involving LGBTQ-focused issues such as medical procedures for trans children.

The groups operate under the presumption that their children’s educators and librarians might be trying to sneak leftist viewpoints (including what they call “critical race theory” and “gender ideology”) into the classroom, or even that they are “grooming” their children.

Increasingly, such parents have trained this focus on books, and have become particularly sensitive to any literary depictions of sex and/or LGBTQ identity — particularly in graphic or comic-book format. Some of the most-banned books in schools across the country are graphic novels and memoirs with LGBTQ themes, including “Gender Queer” and “Fun Home.”

“People are just so uncomfortable with the idea of seeing anything represented visually,” said Kasey Meehan, director of the Freedom to Read program at the literary free-speech activist group PEN America. “Time and time again, when graphic novels are taken, an image is pulled out of context or an image is held up and declared as porn.”

Florida has emerged as a frontier for this movement under the leadership of DeSantis, who is a Republican. Under new laws he championed, educators can face felony charges for making obscene material accessible to students; the state also has a new law, dubbed “Don’t Say Gay” by its critics, that prohibits any classroom instruction on sexual identity or orientation in elementary and middle school, and limits it in high school.

Why are parents complaining specifically about the graphic adaptation?

Critics of the book say they are objecting to the small handful of passages in which Anne describes sexual matters. In one, she discusses a time she asked a female friend if they could show each other their breasts, but was rebuffed. (“If only I had a girlfriend,” she muses.) In another, she describes clinical details of her own vagina.

These passages are Anne’s own writing, and were part of her actual diary. Folman and Polonsky reproduce them in the book and show a full-page illustration showing her wandering through a garden of female nude statues in the Greco-Roman tradition.

This illustration, which is presented as coming from Anne’s imagination, has garnered the most intense blowback from parents. In Facebook groups devoted to book challenges, some members have shared screenshots of the page as evidence of the adaptation’s obscene qualities, questioning why any parent would want their child to read it.

Some people challenging the book have offered other explanations. Tiffany Justice, a co-founder of Moms For Liberty whose Florida district has removed the book, told JTA that she was troubled by the fact that the adaptation only replicates a small percentage of the original diary, while leaving out what she believed to be crucial context: the original epilogue that shifted from Anne’s first-person narration to a larger study of the victims of the Holocaust. (An afterword does appear in the graphic adaptation.)

Inveighing against current child literacy levels she said are woefully low, Justice was also infuriated by the idea that Frank’s diary needed an illustrated version to begin with.

“Anne wrote the diary when she was 13,” she said. “So the diary is written at a level where children of that age can completely understand it.”

What has happened when parents have challenged the book?

The book first grabbed headlines in August 2022, when administrators at Keller ISD, a public school district in the Dallas-Fort Worth area of Texas, ordered staff to remove it (along with a selection of other books) from their shelves. The book had been challenged by a single parent the previous year, and the school’s new board, backed by right-wing special interest groups, had ordered its review policy for classroom materials to be completely overhauled. Any books that had ever been challenged in the district were to be removed from circulation until the matter had been resolved. Following public outcry, the book was returned to Keller’s shelves a week later.

A second Texas school district, Katy ISD outside Houston, had also placed the book under review during the 2021-22 school year, ultimately determining it was only appropriate for high school students.

The book soon landed on the radar of parent activists in Florida. One Florida school district, Indian River County Schools on the state’s Atlantic coast, ruled in April that the book was “not age-appropriate” at any level of instruction, including high school. A parent there had challenged it, claiming that the book “minimizes the Holocaust.”

After a review, the district agreed with the parent, telling JTA it had determined the book to be “a fictional novel,” “not the real diary of Anne Frank,” and filled with “inappropriate content.” The district superintendent issued a statement backing the ruling, citing Florida’s statewide Holocaust education mandate as a reason why the school should not make the book available to students.

The national leadership of Moms For Liberty issued a statement siding with the district — and emphasizing that Anne Frank’s diary is not itself objectionable.

“There are multiple versions of Anne Frank’s diary of varying age appropriateness available to students,” the statement said. “Only this ONE version was removed.”

Justice, the Moms for Liberty cofounder, is a former board member for Indian River County Schools and still lives in the area. She told JTA she does not like the book either and said its removal was a sign of the system working as it should: School administrators took a parent’s challenge seriously and came to a decision.

“If the superintendent and the school board wanted it there, it would be there,” she said. “If the Holocaust education group in the county had wanted it there — these are Jewish people — had wanted it there, it would be there.”

Another Florida school district, Clay County Public Schools outside Jacksonville, has kept the book restricted from student access for some five months and counting, following a single parental complaint earlier this year. That parent, Bruce Friedman, is Jewish, and has become a leading voice of the broader book challenge movement. He challenged the graphic adaptation along with hundreds of other books in his district that he deemed to be inappropriate for students. “As far as I’m concerned, it’s grooming,” he told JTA about the adaptation.

Facing a backlog of book challenges, Clay County in April altered its challenge policy to make it harder for parents like Friedman to file blanket requests to remove many books at once for broadly defined reasons. But notably, the district retained the pending challenge to “Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation” even after its policy change. A final decision on the book is still pending.

How are the book’s supporters responding to the criticism?

Activists opposed to the book banning movement and experts on the diary’s publication history say critics of the Anne Frank adaptation are wrong even about the most basic facts of their objections.

First, while the visual format of the graphic adaptation (which incorporates some surreal imagery) arguably lies somewhere between fact and artistic interpretation, and its rendition of the diary is severely abridged, the book did not invent the passages these parents find objectionable, as some have alleged. Those came, word for word, from Frank herself. Both passages were fully restored to her English-language diary beginning with versions published in the 1980s, largely without incident.

A crucial part of the argument against the graphic adaptation is the idea that both of these passages were excised from the initial English-language edition of the diary. Both Friedman and Fine have told JTA they have no recollection of having read the passages with sexual content in their own childhood memories of the diary.

They almost certainly did, said Ruth Franklin, a book critic and author who is writing a book about Frank and her diary to be published next year by Yale University Press. According to Franklin’s research, the very first English-language edition of the diary did indeed include one of the two passages the parents are now objecting to: the part where Anne discusses her attraction to another girl.

Franklin said that, contrary to popular belief, Otto Frank was the one who pushed for the passage to be included in the diary’s first English-language edition after it was excised from the Dutch original. Otto is often portrayed as having been responsible for removing the passage so as to sanitize Anne’s language for a general audience.

Contemporary parents who insist they did not read the passage as children, she said, are “misremembering.”

“If they were to actually go to the library and open up the edition that has been in print since 1952, they would be unhappily surprised to find what’s there,” Franklin said. “It seems inconsistent to me to go after the graphic adaptation and not the diary itself.”

At least one parent has objected to the unabridged text-based version of the diary before. In 2013, a Michigan mom challenged an unabridged edition of the diary, citing the same passages that today’s parents are objecting to in the graphic adaptation. She argued that the unabridged diary was “inappropriate for the middle school,” and tried to push her daughter’s district to swap out the “definitive” edition of the diary for the original version that excised one of the objectionable passages. The parent’s objection made national news, was the subject of much condemnation and was ultimately rejected by the district.

Conditions in schools have changed in the last decade, with parents in multiple states newly empowered to challenge books in their children’s schools. The movement has caught up not only the graphic version of Anne Frank’s diary but a growing number of other titles with Jewish and Holocaust themes.

Meehan of PEN America suggested that the parents who objected to Anne exploring her sexuality were doing so because of the passages’ latent LGBTQ themes, meaning that the text had become an example of “intersectionality,” or representing more than one marginalized group. Some of the book’s opponents, including Justice, have separately attacked the idea of intersectionality.

“When there are multiple themes represented in a book,” Meehan said, “then that book becomes even more a focus of efforts to remove it.”

For the Anne Frank Fonds, the Swiss group that controls the diary and authorized the adaptation, the situation is clear-cut. From across the Atlantic, the group issued a statement responding to challenges of the diary in all its forms: “We consider the book of a 12-year-old girl to be appropriate reading for her peers.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.